The past months have been challenging for the Collingwood Football Club.

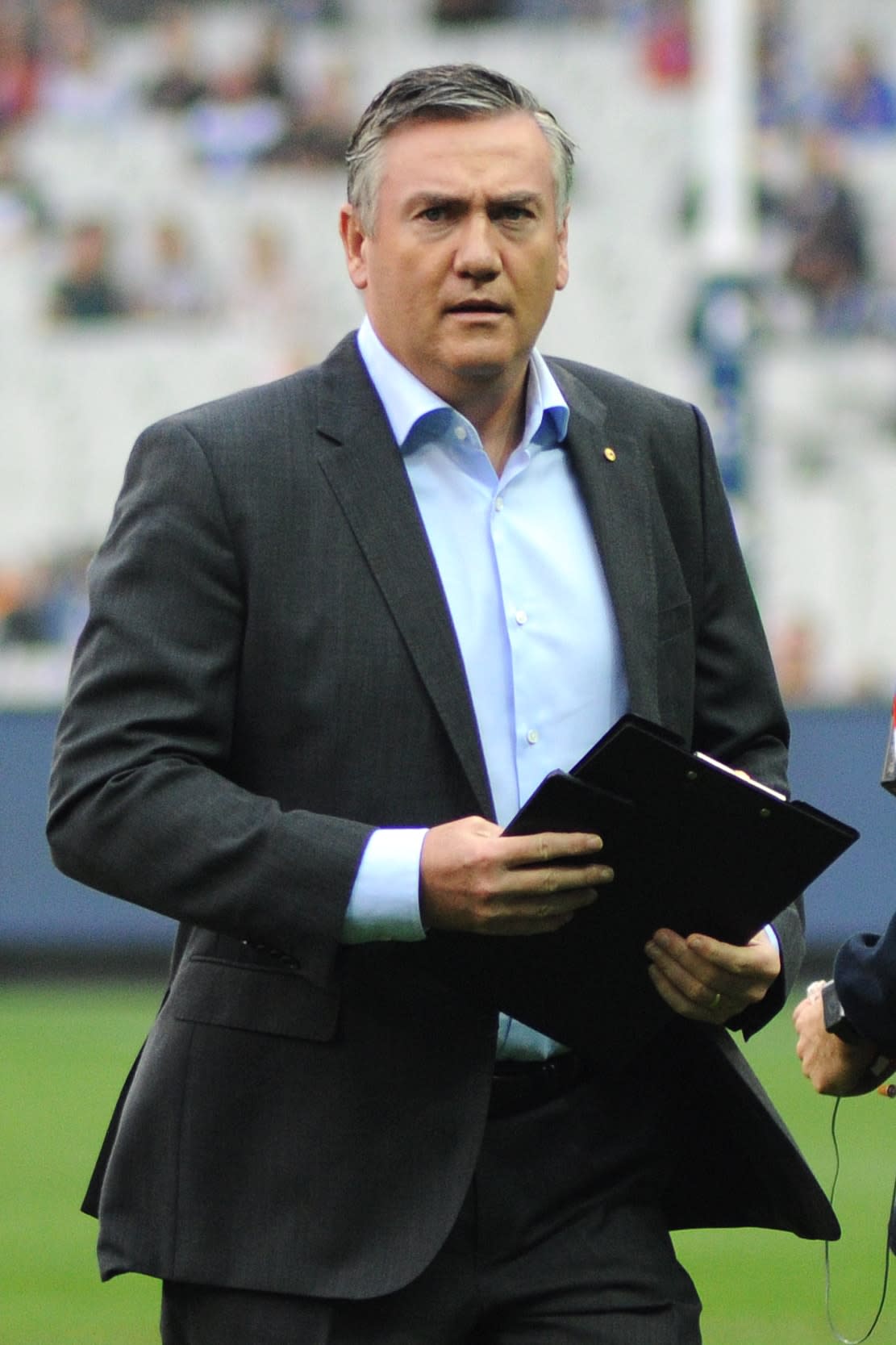

Since President Eddie McGuire’s resignation in February, it’s become embroiled in a factional power play, and now confronts a future without coach Nathan Buckley, who’s announced his resignation.

These events have shifted attention from a more pressing concern – Collingwood’s repeated failure to address systemic racism.

Last July, Collingwood appointed Indigenous academic Larissa Behrendt and Lindon Coombes to review allegations of racism by former player Heritier Lumumba.

In December, they forwarded the Do Better report to Collingwood’s board. It provides an insight into the organisational costs of neglecting to invest in interculturally safe workplaces.

Under McGuire’s presidency, Collingwood did not, and the ripple effect resulted in his resignation and an unseemly internal brawl over the presidency.

Read more: Collingwood racism report and the shame of inaction

When the report’s details leaked to the media last February, Collingwood immediately went into damage control. McGuire declared that the report marked “a historic and proud day” for the club. Within days he was gone, leaving new president Mark Korda to confront the club’s racist history and culture.

From an intercultural perspective, Collingwood failed to foster inclusive and non-racist behaviours.

Being exposed to diversity doesn’t alter behaviours. Individuals must question their taken-for-granted assumptions about who they are, and how they see others. This requires self-reflection on unquestioned assumptions and biases that determine behaviours and interactions with people, as well as a genuine desire for purposeful change towards greater inclusivity and equality.

The starting point is acknowledging that everyone is capable of being racist, and needs to adjust their behaviours, beliefs and biases to eradicate racist practices.

“Collingwood has an opportunity to lead us into a more inclusive and intercultural future, and so deserves our support, once dust settles on the Buckley resignation, and its corporate heavyweights stop brawling.”

As Do Better suggests, this was not done at Collingwood. Taken-for-granted beliefs on what constituted Collingwood values fed a culture that casually discriminated against Indigenous players and those of colour.

At key tension points in Collingwood’s recent past, traditional taken-for-granted beliefs mitigated opportunities for change. So strong were those beliefs that they entrenched racist practices under the club’s collectivist mantra of “side-by-side we stick together to uphold the Magpies’ name”.

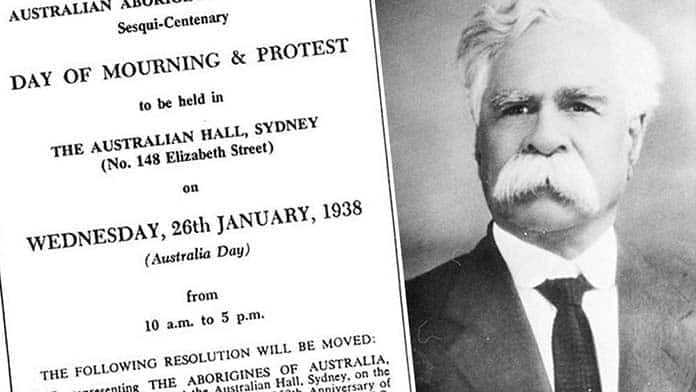

A chequered history

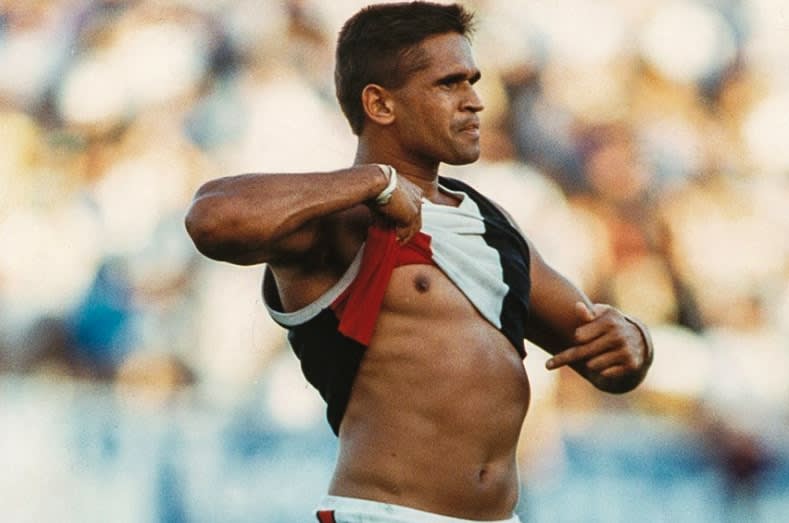

Collingwood has a chequered history when it comes to racism. The most notable incident involved crowd abuse of Indigenous St Kilda players Nicky Winmar and Gilbert McAdam in 1993. In response, Winmar defiantly pointed to his skin, prompting Collingwood’s president, Alan McAlistair, to declare that “[a]s long as they conduct themselves like white people”, they will be “admire[d] and respect[ed]”.

Two years later, Essendon’s Michael Long was racially abused by Collingwood’s Damien Monkhorst, compelling the AFL to ban racial and religious vilification.

As Collingwood’s 1990 premiership captain, Tony Shaw, admitted, on-field racial abuse of Indigenous players was commonplace.

When McGuire took over the club’s presidency in 1998, such practices were on the way out. But McGuire had form in this area. While hosting the high-rating Footy Show in 1999, he sat quietly as Sam Newman appeared in blackface.

Questions should have been asked then about McGuire’s suitability to preside over an AFL club.

McGuire’s part in this Jim Crow vaudevillian stunt exemplified his taken-for-granted assumptions on race. Casual racism was part of the act, evident in his so-called “King Kong gaffe” in response to the racial vilification of Adam Goodes by a young Collingwood supporter during the 2013 Indigenous round.

The presidential McGuire promptly and admirably apologised to Goodes after the match. A few days later, the vaudevillian McGuire suggested on Melbourne morning radio that Goodes could be used to promote the musical King Kong.

Though McGuire again promptly apologised to Goodes, he should have resigned from the Collingwood presidency.

The Do Better report found that “there [wa]s a culture of individuals, if not quite being bigger than the Club, then at least having an unhealthy degree of influence over the Club”.

Though not named, McGuire and his board members were responsible for overseeing and determining this culture. As the report shows, the club had few checks on racist behaviours, and lacked understanding of how to engage with an increasingly diverse workforce.

It had limited experience in dealing with Indigenous players. Prior to 2000, only two had pulled on the Collingwood jumper. To McGuire’s credit, a further 15 were recruited between 2000 and 2015.

In addition, the Congolese-Brazilian Lumumba was signed in 2005, and nicknamed “Chimp.” Despite the obvious racist connotation, the name stuck. It was taken for granted that “Chimp” was acceptable, reflecting a culture of casual racism.

The flashpoint came with Lumumba’s response to McGuire’s “King Kong” comment.

Appearing with McGuire on Fox Sports’ AFL 360, Lumumba labelled the comment racist, adding that it reflected wider community acceptance of casual racism.

Within the club, allegedly, he was accused of throwing McGuire “under the bus”. He had stepped outside the collectivist ethos of “side by side” under which players’ individual identities were subsumed “to uphold the Magpie name”. Lumumba’s blackness, not McGuire’s comment, was the problem.

Lumumba’s marginalisation was complete when he challenged coach Nathan Buckley over a perceived homophobic comment. He was removed from the team’s leadership group, and reminded by Buckley that he was at Collingwood to play football.

Like McGuire, Buckley lacked the intercultural awareness to deal with Lumumba. His KPI was on-field performance.

Lumumba framed football within a quest for self-identity and black empowerment. The club culture could not accommodate his blackness, and he was traded, but not before telling Collingwood that he was on “the right side of history”.

Though Collingwood attempted to become more inclusive with a greater Indigenous presence, its traditional culture was too entrenched.

When Lumumba’s grievances against the club aired in the 2017 documentary Fair Game, Collingwood and the Melbourne football media challenged his credibility rather than addressing his claims of racism.

The onset of the Black Lives Matter movement placed Collingwood in a difficult position. One of its corporate partners, Nike, supported the movement. This, compounded with Lumumba’s continued attacks on Collingwood’s culture, seemingly pressured the board to launch the investigation.

FYI: Do Better - First Quarter Report https://t.co/B5fz3fRVO9— Collingwood FC (@CollingwoodFC) June 4, 2021

Do Better proposed 18 recommendations that were adopted by the board.

Fronting the media, McGuire and Collingwood’s Indigenous board member, Jodie Sizer, attempted to put a positive spin on the report, but misread the room.

McGuire noted the club’s “systemic problems” without mentioning racism. He declared that Collingwood would “learn from our past … and continue to be a wonderful club”.

He sought to salvage the brand, unaware that the club, while wonderful for some, was not a good fit for all. It was not, as he and Sizer claimed, “a proud day”, but it was historic.

Collingwood was forced to confront its history and culture. Given that McGuire presided over the culture, his resignation – and the current players’ apology to anyone who had experienced racism while at the club – were strong and admirable starting points.

Thanks Bucks 🖤

After almost 10 seasons and 217 matches in charge, Nathan Buckley will coach the team for the last time next Monday when Collingwood meets Melbourne at the SCG.— Collingwood FC (@CollingwoodFC) June 9, 2021

The long road ahead

The current power plays don’t instil confidence. If Collingwood wants a more inclusive culture, the board needs to deeply reflect on the club's taken-for-granted biases and beliefs that have fuelled racism.

When the dust settles, the new president should use the report to drive substantive change on racism and diversity in the club and across the AFL.

The club must move beyond trite public relations comments on diversity and inclusion, to changing biases, beliefs and behaviours.

To fully achieve this, Collingwood must engage in a truth-telling process about its past.

As the report emphasised, Collingwood cannot “pretend it can move forward without looking back”. Sizer warned that truth-telling will be painful.

Collingwood’s history is white, working-class and clannish. Truth-telling is a journey that this nation seems reluctant to take.

Collingwood has an opportunity to lead us into a more inclusive and intercultural future, and so deserves our support, once dust settles on the Buckley resignation, and its corporate heavyweights stop brawling and recognise that they have a greater responsibility to sport and the wider community.