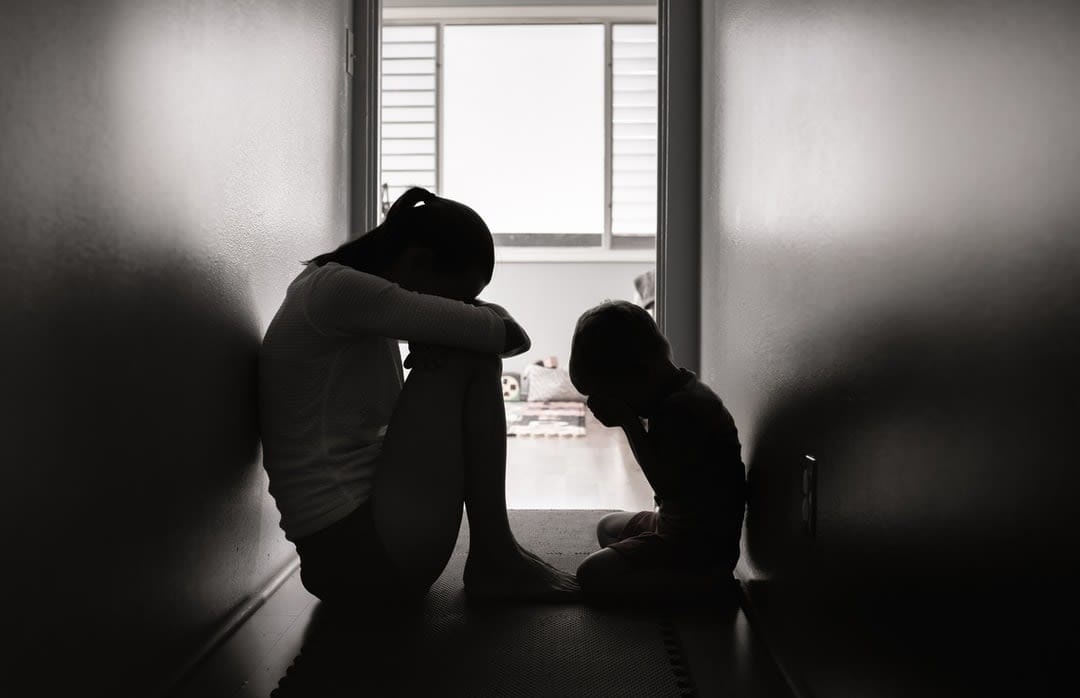

CONTENT WARNING: Physical violence, graphic violence; violence against women and children.

The speakers at March’s Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence fifth anniversary explained the necessity for men to join women in talking about and condemning men’s violence. Prevention, it was made clear, necessitates allyship.

Alongside the now-regular calls to action for non-violent men to denounce men’s violence or to call out the behaviour of others and to be active bystanders, telling our stories of experiences of, or as witnesses to, violence can be part of the required collective action and consciousness-raising that further clarifies the links between masculine norms and violence perpetration.

It’s another way of breaking the silence and of making clear that, actually, as men we also know it’s more than just a few “bad apples”. Violence is enacted by a significant number of “normal” men.

In this spirit, what follows is autobiographical, touching on a few examples of my own experiences as a victim-survivor of men’s violence, and as witness to sustained violence against my mother and acts of random violence against others. In doing so, I’m joining the (most often women’s) voices who draw attention to links between violence against women, and the acceptance and perpetration of other forms of violence.

My life history is littered with experiences of violence. I’ll start with the outliers – violence enacted against me by women. This seems counterintuitive to my point, but bear with me...

One of the rebuttals by deniers or minimisers of men’s violence is to point to acts of aggression by women. These, of course, do happen – and while research shows us that it’s often in self-defence, or in the context of retaliation and escalation, that’s not always the case.

On a warm early summer evening in 2014, on a busy high street in England, after trying to walk away from a brewing argument, I was slapped hard across the face by a woman with whom I had a romantic relationship. The sting was sharp, my skin reddened, and my ears were ringing for a few minutes.

This was the height of violence I’ve experienced from a woman, but not the only violence. The other instances are, together with this one, countable on just one hand.

These include being called a “f--king Paki” and shoved over by a young woman at a nightclub when I was around 20, and also, while on a school exchange trip to France when I was about 13, being targeted by two teenage girls in an unprovoked (possibly racially-motivated) act; one of them slapped me around the face, and the other immediately spat in my hair. My French was never good, so I didn’t, and never have been able to, understand their rationale.

I don’t want to play down these experiences. They were real, and all painful in both specific and overlapping ways.

But, crucially, they sit in absolute contrast to my experiences of men’s violence in both frequency and ferocity. That is, mirroring what we know from reams of academic research, my experience of men’s violence both as an adult and as a child was quantitatively and qualitatively different to experiences of violence by women. For example, in my teenage years I had my nose broken twice in random unprovoked attacks by young men, once being kicked in the face, another time being headbutted.

The qualitative differences in the ferocity and impact of such one-off acts are mirrored in the sustained patterns of violence and controlling behaviour I experienced and witnessed as a child.

An important caveat to start, and something that often goes ignored in these stories, is that a pattern of violent or aggressive behaviour isn’t indicative of a life with nothing other than violence.

“Normal” life existed, but it was punctuated with frequent violence and a climate of fear that waxed and waned in terms of its impact on our daily life. There were many times when my childhood looked as normal as any other, often for weeks at a time.

My mother’s first husband, my first stepdad, is an exemplary case that shatters the problematic “good men don’t hit women” rhetoric. I have relatively few memories of any overt violence prior to age five, though my mum’s accounts signal a fiery temper and controlling behaviours in these early times.

There was lots of behaviour management that involved threats and occasional use of physical force against me and my siblings. A smack around the head or legs, a firm grabbing by the collar.

In those days, I never considered those actions to be violence. They were discipline methods, relatively light-touch, kind of normalised, yet still relatively infrequent. They were also not to be cried at. Tears were to be held back or they were met with a warning: “Don’t make me give you something to cry for.”

Read more: Why we need to focus more on the needs of children in domestic and family violence responses

One vivid case of what was to come occurred around 1983. I was sitting on the arm of a living room chair, and my stepdad repeatedly told me to get off the arm. I didn’t heed. After a minute, the chair flipped over, and I crashed to the ground. His reaction was immediate – as I clambered to my feet already crying, my punishment for failing to obey was a firm punch to the side of the body, and the impact was so hard that I urinated.

It wasn’t the fear, which was plentiful. It was the force – “like he would punch a man”, my mum always tells me. I stress this not to deny the crying from the pain, but to underscore the ferocity.

When physical violence perpetration began in earnest against my mum, its acceleration was prolific. What started with years of being seemingly (to many) a “good man” – a breadwinner, a protector, a family man, a sociable and gregarious host – gradually became a pattern of power and control, jealousy, financial isolation, property damage. A few slaps to put Mum back in her place escalated quickly.

One most enduring and clearest memory is the sound of running footsteps as my mum ran up the stairs into my bedroom, with nowhere else to go, huddled and hiding behind me, screaming, “Please don’t, please don’t” as my stepdad had attacked her with two wooden bannister poles he had just then kicked out from the stair rail.

She escaped further violence that day. He stood in the doorway and threw the pieces of wood towards – but not quite at – us and stormed off as they cracked against the wall.

A ‘two-year reign of terror’

Kicking out a banister pole to beat my mum with, though, became a bit of a favourite. A two-year reign of terror – I genuinely do not think that is an overstretch – followed. Regular bruises for my mum, dunking my two-and-a-half year old brother’s head repeatedly in the bath water because he resisted washing his hair, hard open-hand striking on the chest of my quadriplegic brother “because he sneezed out his food”, regularly smashing up the house, and, in another of my least-cherished memories, proceeding to gaslight me in a way that scares and scars me to this day.

He was out at work, Mum had some adult friends around; I think it was a party. In my boredom, I was throwing a tennis ball against the wall, but accidentally broke a small window pane. With deep-seated fear, I grabbed a kitchen knife, proceeding with a panicked voice to explain to my mum and our guests that he would hurt me in retribution for what I had done.

The adults tried and failed to talk me down, but when he got back he played it calmly, even caringly. He situated me as hysterical, nonsensical, resulting in a flood of tears on my part. Making me look stupid, and keeping up his appearance, was all he needed that day. No threat of something to cry for, no physical reprisal. Just shame.

As their tumultuous relationship ended, the sounds of his fist literally cracking Mum’s jaw was accompanied by an astonishing smashing up of the house, piling high the broken pieces of chairs, TV cabinet and other furniture in the centre of the living room, shooting several holes in the ceiling with an air rifle, and, to sign it off, daubing “SLUT” in large white painted letters on the hallway wall.

Several weeks later, with him seemingly having exited our lives, another vivid memory. It’s night. I’m sleeping. Mum rushes into my bedroom: “Jimmy’s coming, Jimmy’s coming!” They had both been at the same pub that night, and following some cross words, there was a clear verbal threat that he was going to the house to kill her children.

As their tumultuous relationship ended, the sounds of his fist literally cracking Mum’s jaw was accompanied by an astonishing smashing up of the house.

We had to leave immediately. Putting on a Parka over our pyjamas, but no time to put on my shoes, we walked barefoot for nearly a mile across the village, my mum carrying my brother who is disabled, and my cousin, who had been babysitting, carrying my baby sister. Me, holding the hand of my smallest brother, who thankfully was a toddler and therefore able to walk; at eight years old, carrying a three-year-old for that distance was impossible.

Our refuge for a few days was the one-bedroom flat of a local man, not a stranger but not a friend; staying with our immediate family was deemed too risky.

Things settled – we go back home, he gets on with his life, gets remarried, has more kids. We didn’t get killed. Nothing to cry about, then; nothing to discuss. The silence around violence against women and children continues.

Reminders linger, though. About 10 years after this incident, I’m leaving my mum’s house to go to work. He’s at the doorstep talking – calmly – to my mum about the health needs of my brother with disabilities. I find this odd; maybe it’s a pang of conscience on his part that makes him come to enquire after so many years of distance and virtually no contact (thank goodness!).

As I pass them at the door, I give him a cursory nod. He makes a “joke” about how my goatee beard looks like a “pussy” on my face. I ignore him, so he says it again. I reach the car and, as I get into the seat, I hear him call out to me: “Oi, don’t think you’re too big for a slap.” It’s mischief, not a threat. A reminder, not a promise.

Stepdad No.2 was a similar pattern, with a year of almost no problems. Other than one hard open-hand slap across the face, in the presence of three of my friends when I was age 12, I largely got away without physical reprimands.

Enough fear was generated, though, through acts of aggression and intimidation against others – mostly towards my little brother, but periodically in profound ways against my mum, and at times towards others.

One visceral memory revolves around the time when, during an argument in the kitchen, he was shaking my mum around by her jumper. Drawn to the noise, I went into the room to see my cousin, a young woman, intervening, dragging him away, and with the help of her friend trying to push him towards the back door, shouting at him: “Leave her alone, just go!”

His reaction was a swift left hook, breaking my cousin’s nose and spattering her blood up the full length of the side of the double-stacked washing machine and tumble dryer. His last act as he left was to turn towards the back door that had been slammed as he exited, and then smash his fist into the door window, shattering the glass everywhere.

This was a particular low, among more than a decade of lower-level acts of intimidation, aggression, financial isolation and property damage.

One thing that stands out in my mind is the air of apprehension in the house after he would come home from work and run his fingers along the surfaces looking to see if my mum had sufficiently dusted. His red, angry face was a tell-tale sign of the intimidation that was to follow.

One time, that intimidation included accelerating the car towards us – Mum, me and one of my siblings – and slamming on the brakes, with the screech of the tyres being the symbolic violence of choice that time.

I’m trying to avoid a book-length story, so I’ll draw the line there. I would encourage other men, though, to share their experiences or observations of men’s violence against women and children, and even against other men.

In telling these stories, we can go about challenging the tendency to downplay the significance and prevalence of men’s violence. We can make clear that a considerable number of men, often seemingly “good men”, perpetuate violence.

The obdurate, defensive chorus of “not all men” gets us nowhere. If we join women in telling our stories of violence – to one another as much as anything else – we could push back against the uneven amount of energy committed to arguing that such violence is “nothing to do with masculinity”.

We can commit to understanding and to overcoming that violent men are acting out the gender norms and values with which they’ve been socialised, in a context of unequal gender relations.

We can break our silence, and support the push towards ending violence against women and children, and people of all genders.

If you’re affected by, or have experienced, family or domestic violence or sexual assault, you can call:

1800RESPECT (1800737732)

Mens Referral Service (1300 766491)

Mensline Australia (1300 789978)

Lifeline (131114)

Kids help line (1800 551 800)

Beyond Blue (1300 224636)