How do you measure the worth of a tree? A forester sees the value of the timber, an environmentalist sees a habitat for possums, insects and birds, and an Indigenous Australian sees the tree as part of the living web of Country.

“When we look at the various Aboriginal languages around Australia today, there are not many words that translate as land, whereas we have many words that translate as Country,” Indigenous scholar and artist Brian Martin explains. “So in Country, the non-human has the same importance as the human. Trees are really important to the relationality that we have with Country.”

Dr Martin and fellow Indigenous artist, colleague and brother, Associate Professor Brook Garru Andrew, have received Australian Research Council funding to lead a study into the significance of trees to Aboriginal people of Southeastern Australia.

Both men are from this part of the continent. Dr Martin is a descendant of the Murawari, Bundjalung and Kamilaroi peoples from northern NSW and southern Queensland; Associate Professor Andrew has Wiradjuri (central NSW) and Celtic heritage.

“There’s been this whole push historically that the authentic Indigenous culture comes from remote communities in the more northern parts of Australia,” Dr Martin says. But Indigenous culture survived in the southeast, he says, despite the more intense contact with Europeans, “and there’s a lot of objects, artefacts, cultural material that’s held in museums around the world from southeast Australia as well”.

Project to document the artefacts held across the world

The multi-faceted research project aims to document the artefacts made from southeastern Australian trees – including bark shields, canoes, coolamon (curved, multi-purpose vessels) – that are now held in some 220 overseas museums. In Britain alone, some 32,000 Indigenous Australian artefacts have been identified. The ARC grant includes funding for a PhD student to assist with this research.

“You’ve got to remember the impact of colonisation on southeast Australia was quite evident not only in massacres and policy and so on, but also the amount of theft of cultural material,” Dr Martin says.

One of his hopes for the research is that it will improve Indigenous access to these materials.

More than a guulany (tree): Aboriginal knowledge systems is the name of the Indigenous-led project that will also involve conversations with Indigenous communities throughout southeastern Australia about their relationship to trees. Guulany is a Wiradjuri word for tree.

Talking and listening to Indigenous people is the best way of learning more about the many meanings a tree might have, Dr Martin says. Some trees are recognised as significant because of the scar in their bark, indicating that it once provided material for a canoe, for instance. But “a tree can also have significance regardless of whether a human being has touched it”, he says.

“It doesn’t have to have this human interaction for it to be elevated and protected. That’s also what we want to uncover.”

Misunderstanding in the non-Indigenous world

Sadly, this intangible aspect can be unappreciated in the non-Indigenous world, he says. It's one reason why the recent felling of trees in Djab Wurrung Country has triggered so much grief.

On 23 October, a number of trees were cut down near Buangor, about 180 kilometres west of Melbourne, as part of a $157 million project to add extra lanes to the Western Highway. At the same time, about 50 protesters were arrested at the site.

The felled trees included a yellow box, identified as a "directions tree" by the Djab Wurrung, who two years ago set up a protest camp – the Djab Wurrung heritage protection embassy – to save the trees. Placentas were once mixed with seed and buried beneath directions trees, tying them to a child’s life.

In protest, Djab Wurrung woman Sissy Eileen Austin, a member of the First Peoples’ Assembly representing Aborigines in the Victorian treaty process, said she would step down from this elected role. The tree-felling has been compared to Rio Tinto’s destruction of the Juukan Gorge caves in Western Australia in May.

Work on the site has stopped until February, after Supreme Court Justice Jacinta Forbes granted an injunction.

Supreme Court grants Djab Wurrung sacred tree injunction on Western Highway project.https://t.co/MV4uGt4aRt— ABC Indigenous (@ABCIndigenous) 3 December, 2020

The "directions tree" was not listed as significant by the Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation, which is the registered cultural manager for the site. Last year, the Eastern Maar reached an agreement with the Victorian government to save 15 trees. These trees were clearly labelled, with a buffer zone established around them. They included birthing trees, where Aboriginal women gave birth in the hollows; one is believed to be 800 years old.

But members of the Djab Wurrung heritage protection embassy say the roadworks will not only destroy trees that are sacred to women, but also trees linked to Djab Wurrung songs and dreaming. The trees connect the Djab Wurrung to nearby Mount Langi Ghiran, the black cockatoo dreaming site, and to the Hopkins River and the eel dreaming.

“How do we measure what cultural heritage is?” Dr Martin asks. “It’s really important to know that this is the politics around who consults with who. The consultation and governance with Indigenous communities is so complicated because of colonisation. The government system that we have essentially tries its best, but its best isn’t good enough.”

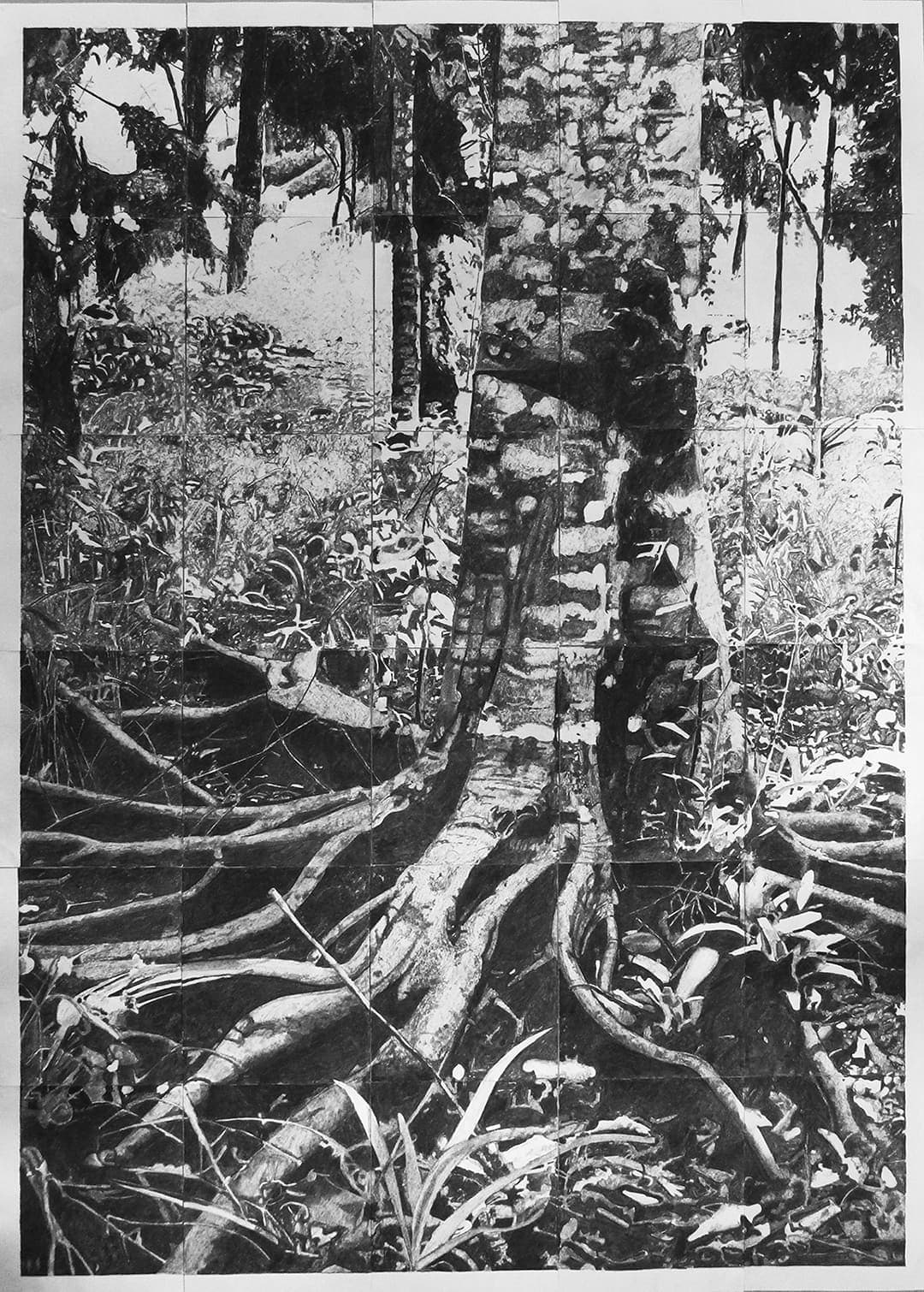

In his own practice, Dr Martin walks around his Country and takes black-and-white photographs, on film, of the trees that speak to him. He describes the process as drawing with a camera. Then he painstakingly renders these images in charcoal (above). The finished works often include the fallen bark and leaves; he calls them Countryscapes.

“They are quite large-scale, just over two metres by five-and-a-half metres, to give this idea of the enormity of Country and the tree’s relationship to it.”

Dr Martin has been making these detailed drawings for almost 20 years. The philanthropic trust Eucalypt Australia this year awarded him the 2020 Bjarne Dahl Medal for his contribution to celebrating and documenting eucalyptus trees. He also received the Bjarne Dahl Fellowship 2021 from the trust to make images of 10 ceremonial scar trees.

Indigenous people have much to teach the rest of us about the value of trees, and how to care for them, he says. Last summer’s devastating fires revived interest in Indigenous cultural burning practices as a way of protecting the land from wildfires; the COVID-19 crisis has deepened our understanding that we are related and interdependent; and the destruction of Djab Wurrung trees – and the loss of community trust that went with this – has lent a sense of urgency to his research project.

Read more: Indigenous practice of cultural burning and the bushfires prevention conversation

“If you want to understand Country, you go to custodians, you ask them the question,” Dr Martin says. “I think that’s what’s missing, the idea that local knowledge is really important – consultation, deep listening and deep engagement with traditional custodians, recording those narratives and seeing how they relate to concepts like sustainability.”