If you’ve ever wondered about the benefits of the Rainbow Laces campaign in the UK, you wouldn’t be alone.

Sport organisation CEOs, board members, corporate sponsors, and even LGBTQ partners have all asked us if there's any evidence that the Rainbow Laces campaign, or Pride Games in other countries, help to end homophobia and make sport more inclusive for LGBTQ people.

Until very recently, it was impossible to answer this question. Over the past 50 years, there have been thousands of studies conducted into the problem of homophobia in sport (see this timeline). In contrast, there's been almost no research focused on solutions, including studies conducted to determine whether campaigns such as Rainbow Laces have any benefits.

Unfortunately, there's no evidence that the Rainbow Laces campaign, as it's done now, helps to stop homophobic language or make sport more inclusive and welcoming for LGBTQ people. However, with a refocus of the campaign away from professional clubs, and towards amateur clubs and teams, Rainbow Laces could help to reduce homophobic language in sport.

Why do we need Rainbow Laces?

There's a scientific consensus among International Olympic Committee scientists and also sport medicine scientists that homophobic and transphobic behaviours and the exclusion of LGBTQ people from sport remain serious problems that require urgent solutions. This is because of the harm caused to LGBTQ people, particularly youth.

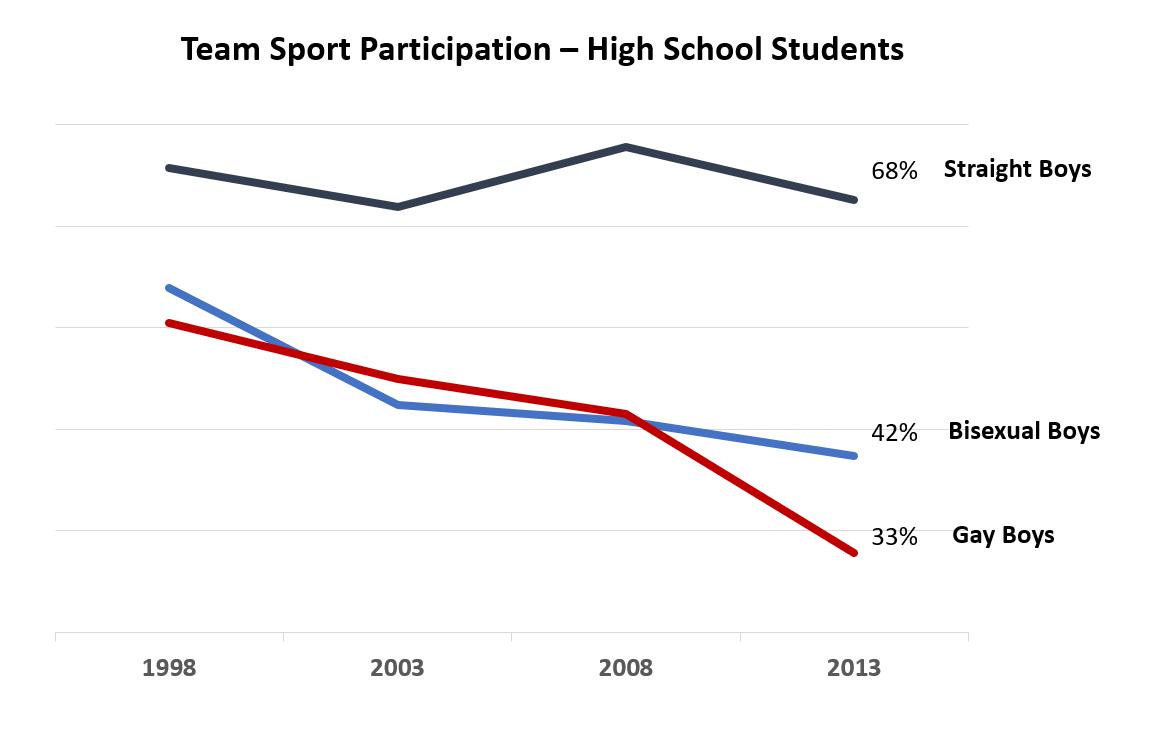

Gay and bisexual boys play team sport at around half the rate of their peers. Many avoid sport because of the regular use of homophobic language. We released an international study this week that found more than half of gay and bisexual youth (ages 15 to 21) report that they've been the target of homophobic bullying, assaults, slurs, derogatory jokes, and other forms of behaviours in sport.

Those who come out of the closet to their teammates are much more likely to report being the target of this behaviour. This is a serious public health problem. Being the target of homophobic behaviour, or even just being exposed to homophobic behaviour, increases the risk a LGBTQ young person will self-harm, or attempt suicide. This is why a recent, unprecedent joint statement from all United Nations agencies called for urgent action to stop homophobic behaviours.

There's also often an assumption that homophobia isn’t much of a problem in female sport, because most female athletes are assumed to be lesbians. This false stereotype itself highlights the homophobia problem that impacts all women and girls who play sport.

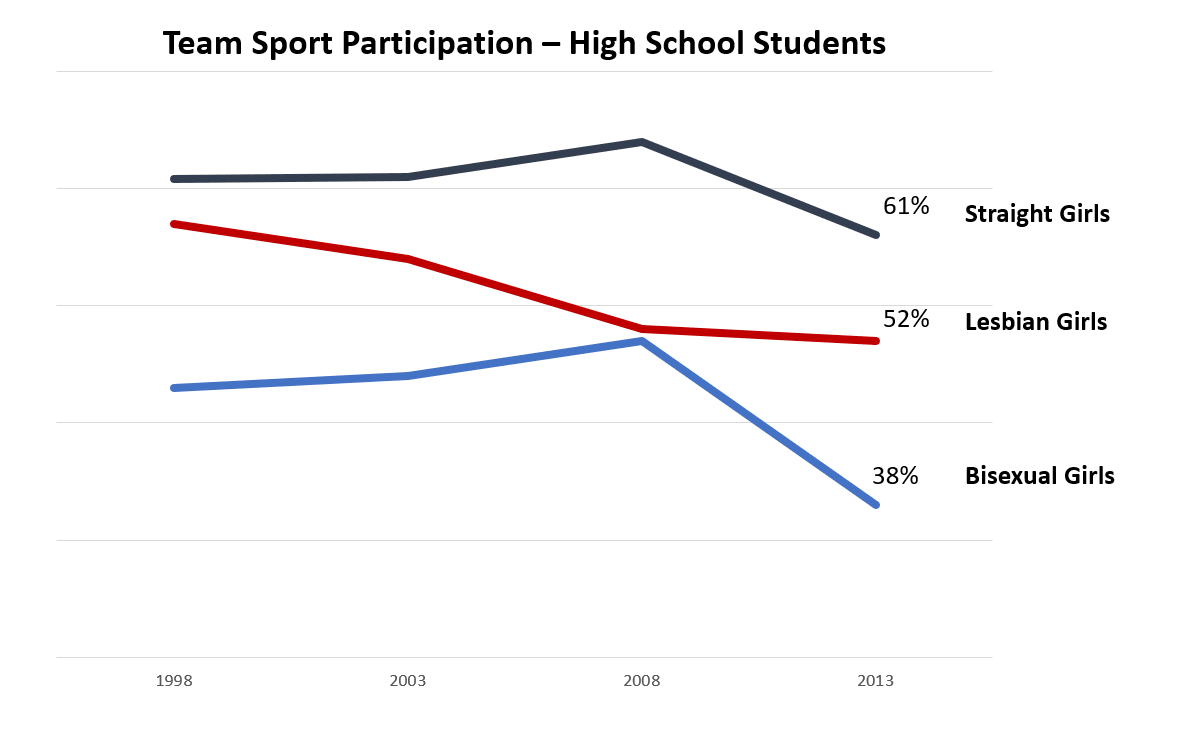

Lesbian and bisexual females actually play team sports at about the same, or slightly lower rates, than peers. Our research has found young females who stay in the closet are less likely than males to report being the target of homophobic behaviours. However, if they decide to come out, they're also much more likely to report being the target of discriminatory behaviours. But the drivers of this discrimination are very different than those in male sport, and are more related to sexism and gender norms about women, than homophobia.

We'll need to develop unique solutions to fix this problem. This highlights why one-size-fits-all approaches to fix “homophobia in sport” or “LGBT-phobia” are destined to fail, as they're based on the premise that you can solve a broad range of problems, all with different causes, with the exact same solution.

Can Rainbow Laces help fix homophobia in male sport?

One of the strongest pieces of evidence that the current approach to Rainbow Laces doesn't help drive change in behaviours in male sport comes from research conducted in both Australia and Canada in ice hockey.

The NHL has been holding Rainbow Lace-style “Pride Games” for nearly a decade. All professional NHL teams host these annual rainbow-themed events, with players putting rainbow tape on their sticks, and the teams post pro-LGBT messages on social media.

Despite these efforts, homophobic language remains rife in ice hockey, and gay and bisexual players remain largely invisible at all levels.

The NHL is the only major North American league to never have a player (current or retired) come out as gay or bisexual. Just a few players have come out in the minor leagues, and they've all been in Europe, including British player Zach Sullivan.

In the UK, sports teams have also been holding Rainbow Laces for the past seven years, yet homophobic language also remains common. Two-thirds of teenage football players and nearly half of male rugby players admit to recently using homophobic language with teammates (for example, fag), which is generally part of their banter and humour. At the amateur level, gay and bisexual males remain invisible.

However, recent research suggests that refocusing the current Rainbow Laces campaign, which is underway, away from professional teams and strongly towards amateur sport settings could help fix these problems. We also need to change the education that is being delivered.

Why is homophobic language used in sport?

We consistently find athletes who use homophobic language are generally not doing this to express hate or prejudice towards gay people. Only a small proportion of athletes seem to be using homophobic language because they're homophobic. There's no relationship between these attitudes and this behaviour.

Athletes with positive attitudes towards gay people are just as likely as those with negative attitudes to self-report recently using homophobic slurs.

Our research has found most male athletes use homophobic language to conform to the behaviour of others around them. They perceive there's an expectation in sport to use this language, and so they need to use the slurs to indicate to others that they're part of the group. We found a strong statistical relationship between the use of homophobic language and social norms, which are the unwritten rules we follow in each social setting, but we found no relationship between this language and homophobic attitudes.

Read more: Homophobic language in sport: the disconnect between what people say and how they think

We consistently find athletes who use homophobic language also believe it's harmless because they assume that everyone on their team is straight. The majority of male athletes also, bizarrely, believe a gay person would feel "very" welcome on their team despite the frequent use of homophobic language.

The current generic messaging about "celebrating inclusion" used by professional teams that host Rainbow Laces or Pride Games isn’t helping to fix this misperception. The people who are using this language are not "homophobic". In fact, they generally want to be – and think they are already being – inclusive of LGBTQ. They're already sold. We now need to tell them how to be inclusive.

We need the teams that host Rainbow Laces to use the events as a vehicle to deliver clear and direct education about the specific words that male athletes need to stop using, and why.

These events cannot be one-size-fits-all solution to the different forms of discrimination experienced by males, females, and trans/gender-diverse people. Different problems, with different causes, need different solutions. That's not surprising.

We also need to refocus these campaigns away from professional sport and put our energy into promoting the adoption in amateur sport. This is because attending a Rainbow Laces game, or a Pride Games, doesn't change attitudes or behaviours.

However, the same cannot be said for being a participant in one of these games. Recent research has found athletes who play on teams that host a Pride Games, following the approach in this video, which is similar to how Rainbow Laces are held in the UK, use 40-50% less homophobic language. Players on teams that host these games, and also receive education about why LGBTQ people feel unwelcome in sport, are also more confident to challenge others who use homophobic language.

What needs to be done differently?

It’s fair to say that we all want people to feel welcome and safe to play sports. We also need to stop the harm to LGBTQ kids from being the target of homophobic behaviours. To do this we need to start using science and evidence to guide our approaches to fix these problems.

We need to refocus away from the marketing messages and "activations" that are currently central to the Rainbow Laces campaign. We need to shift our focus, as I know is already underway, entirely towards amateur sport environments.