About a year ago, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison was feted at the White House by US President Donald Trump with a military band, a 19-gun salute, and a fancy state dinner.

Australia was riding high, experiencing an unprecedented run of prosperity, largely fuelled by China’s giant appetite for our mineral and agricultural resources.

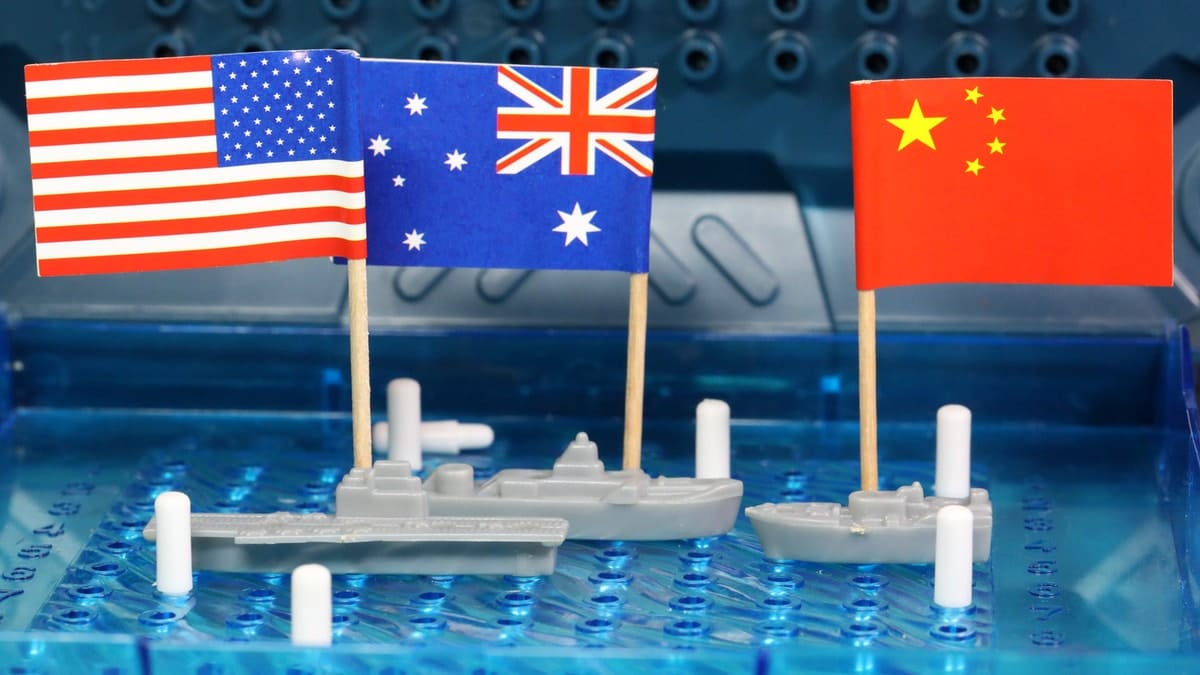

But the world’s been turned upside-down since then, and Australia’s perceptions of our two great and powerful friends aren’t what they were.

The US remains our most important ally, but under Trump’s presidency the country has become more isolationist, more unstable and divided. His response to COVID-19 has been heavily criticised, with the US, to date, recording the highest number of COVID-related deaths and infections worldwide.

China continues to be our largest trading partner, but in other respects our relationship is at a low ebb.

China responded to the Australian government’s call that an inquiry be held into the origins of COVID-19 by stopping imports of Australian beef, barley and wine. (When the EU called for this inquiry, China agreed to it, but China’s harder line on Australia remains). Now, there are reports that China has also ordered that state-owned energy providers and steel mills stop importing Australian coal.

The last two remaining Australian journalists working in China – the ABC’s Bill Birtles, and the Australian Financial Review’s Mike Smith – left the country on 8 September, after a five-day diplomatic standoff. A third Australian journalist, Cheng Lai, who worked for Chinese state media, has been detained since August.

How can Australia navigate these perilous diplomatic currents, while also protecting its national interests?

The wildcard is that leaders in China and the US are more willing to disregard international rules, says Monash University political analyst Dr Remy Davison.

“The Trump administration has reduced its support of global institutions,” Dr Davison says. “We've seen the US withdraw from the World Health Organisation, withdraw from the UN Human Rights Committee, Trump’s refusal to appoint judges to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) appellate panel.” (This has led to the EU forming a substitute panel – the “Multi-party interim appeal arbitration arrangement” – which China, Canada and Australia have also joined.)

“Paradoxically, China has become a more fervent supporter of trade rules,” he says, “because predictable and stable international trade rules serve China well. And we’re seeing that the WTO recently ruled that the US tariffs on China were unlawful.”

The changing international legal landscape

The US has questioned international legal institutions under previous presidents – it’s not a state party to the International Criminal Court, for example, and a recent Trump executive order has sanctioned ICC prosecutors – “but now it’s undermining institutions that it established itself”, Dr Davison says. “The US wins 90% of the cases it takes to the WTO. So why would it undermine the WTO? Trump has done that.”

On the other hand, “China has been getting much tougher on international business in the last few years. It’s throwing its weight around,” Dr Davison says. The impenetrable links between Chinese companies and the Chinese state is an added complication.

“If there’s a second Trump administration, then you can throw all the predictions out the window. Trump, like the proverbial bull in a china shop, could do irreparable damage by withdrawing the US from international institutions like the WTO, possibly NATO, maybe even more – or all of – the UN.”

In 2018, in response to security advice, the Australian government banned Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE from bidding for Australia’s 5G network. Huawei has also been banned by the US. The US advised European allies – including Britain – that they were putting their intelligence networks at risk if they used Huawei-supplied communications technology. The UK subsequently banned Huawei from being used in its 5G networks.

Tensions have also been building between Apple and China, where most of Apple’s products are manufactured. President Trump has banned US companies from doing business with WeChat (the app is central to daily transactions in China) due to data security concerns. The move means Apple is in danger of losing its customer base in China.

Under President Xi Jinping, China has also been more willing to ignore international law.

“China has been in material breach of maritime law by militarising the South China Sea, by threatening freedom of maritime passage in the East China Sea, for Japan, the United States, and South Korea,” Dr Davison says.

Will these tensions translate into war? Former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd warned in August that the risk of war between the superpowers was greater than it had been in 50 years.

“There are obviously flashpoints,” Dr Davison says. “North Korea, the South and East China seas, and the Taiwan Strait, which is part of the South China Sea dispute. Xi has taken advantage of the unwillingness of the United States to draw red lines and have conflicts with China, or even maritime scuffles with China.

“There was a reluctance to do that under Obama, and there’s certainly a reluctance to do it under Trump as well.”

Since 2013, China has been building islands in the Spratly and Paracel Islands region of the South China Sea to boost its territorial claims. In 2016, a tribunal constituted under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ruled against China in a dispute with the Philippines over the Spratlys.

'Blatant refusal' to comply with ruling

China has refused to recognise the tribunal’s decision. Dr Davison says he doesn’t know “of a single example where there’s been such a blatant refusal to obey an international maritime ruling, ever”.

“China continues to militarise these disputed areas, as there’s thought to be quite a lot of oil under there, and gas,” Dr Davison says.

Nevertheless, he can’t “see any upside in a war with China”.

“The United States isn’t about to start one, and I don’t see why China would start one when China can still be very easily blockaded in terms of its energy supplies through the Malacca Strait, by the United States. China would run out of oil very quickly if there were to be any conflict in the South China Sea, for instance. Why would they try to damage their own trade routes?”

Read more: After the bomb: The changing face of the world order 75 years on

He’s also soothing about Australia’s long-term relationship with the US. The alliance has previously weathered civil unrest and unpopular presidents, he says, citing the violent anti-war protests under Nixon.

The ANZUS alliance remains a cornerstone of Australia’s security arrangements. “We buy so much defence equipment from the US,” Dr Davison says. “And then there’s the economic relationship. The US is by far the biggest foreign investor in Australia in terms of portfolio investment, equity in the stock market, and so on. The second-biggest – a distant second – is Britain.”

The US is also central to how Australia hopes to manage China’s growing might and influence in our region. The US pivot to Asia, announced by President Obama in 2011, has been supported, and in some ways extended by President Trump.

Australia has also developed strategic relationships with Japan, India and Korea. Our defence budget will increase by 40% over the next 10 years.

While Australian politicians and business leaders may disagree about how to handle our economic dependence on China, our national strategy involves negotiating free trade partnerships with many countries – including China.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership – a 15-state agreement with the ASEAN nations and China – is due to be signed in November. New free trade agreements are also being negotiated with the EU and UK.

Trade diversity is the key

“So, the message here is, we have a diverse network of economic partnerships around the world. Maybe down the track we will have one with India as well. They’re intended to diversify our trade so that we don’t have all our eggs in one basket,” Dr Davison says.

While President Trump is a “neo-isolationist”, Joe Biden, the presidential hopeful, “supports NATO, he supports multilateral security, and he supports the United States’ global role in the world, which Trump doesn’t. But because Biden knows that Trump has succeeded in making China a domestic issue, he’ll probably have to be tougher on China.”

That is, if Joe Biden is elected.

“If there’s a second Trump administration, then you can throw all the predictions out the window. Trump, like the proverbial bull in a china shop, could do irreparable damage by withdrawing the US from international institutions like the WTO, possibly NATO, maybe even more – or all of – the UN,” Dr Davison says.

“Trump wouldn't have any constraints upon him in a second administration.”