Even before COVID-19, aged care was at a crossroads. Earlier this year, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety heard evidence about how the sector was lagging behind in innovative technologies to improve the quality of life of its residents, and the struggles and barriers it faced in successfully implementing technology-assisted care.

Later, as the sector’s failures were further exposed and its residents hit hard by COVID-19, the commission held hearings to inquire about aged care accommodation and the sector’s responses to the pandemic.

So, what role could technologies – and specifically AI – play in this context?

We've seen a growing interest in AI technologies to assist older peoples’ everyday lives. This interest is partly due to a rapidly ageing population in many countries, which has posed challenges in ensuring quality of life, inclusion, and adequate care in old age. The use of AI in aged care seems to present both opportunities and challenges, yet it is still under-researched, and discussions about its applications remain hypothetical.

This is understandable given that the digitalisation of aged care has just begun. There's little point investing in potentially expensive technologies until we have a clear sense of what AI entails, how it may be applied, and how it's viewed by those who have a stake in its development and use.

How can AI be successfully developed and implemented in aged care?

What our research shows

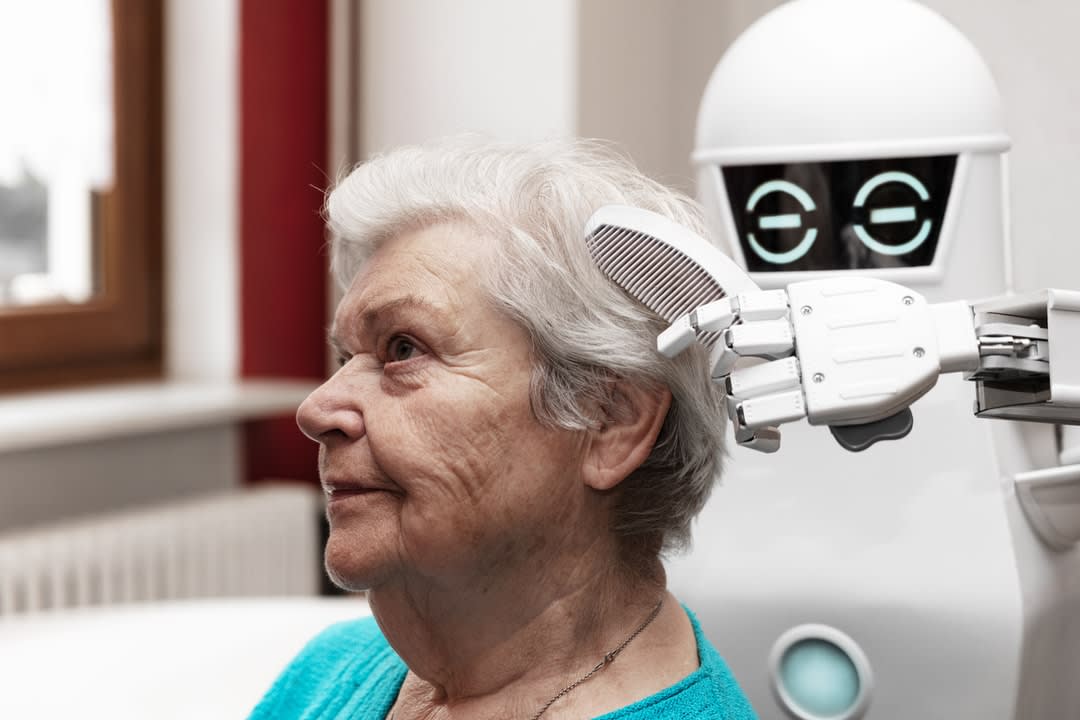

The one-size-fits-all does not work – AI should be flexible and accessible for a diverse range of aged care residents.

Aged care residents tend to be viewed in a homogenous way, which ignores their different ages, cultures, religions, socioeconomic backgrounds, physical and mental capabilities, and life histories.

Residents also have different health issues and experiences of physical and cognitive decline. As with other emerging technologies, we know that the one-size-fits-all approach is limited; only flexible, personalised and accessible AI technologies can meet the diverse needs and aspirations of older people.

For example, older adults with cognitive and non-cognitive impairments can perceive things in very dissimilar ways. One of our interviewees (an AI engineer) said that healthy older adults perceived a reminder function through a speaker as helpful, whereas others with dementia found it frightening.

We're not able to predict all the unanticipated negative consequences of AI in care, but we need to recognise potential outcomes and map as many as possible. "Co-designing" innovative technologies with multiple stakeholders can be a way of achieving this.

Aged care service providers, frontline workers, care recipients and family carers need to be involved in the process of designing AI if we want the technologies to be useful and inclusive.

Understanding the factors shaping AI's delivery

COVID-19 has shone a light on the persistent issues experienced by the aged care sector, including chronic staff shortages, the small number of clinical staff per shift, inadequate resources, poor training for many staff, and an underpaid workforce who often need to work across multiple facilities to make a living.

In addition, we know that the capacity to provide holistic and person-centred care is limited by shortcomings in communication and information-sharing, professional boundaries, a death denial culture, and the conventional biomedical care approach.

Despite the promotion of consumer-directed, person-centred care by the Australian government, this is unachievable with the current structure and practices of residential aged care. It is, thus, imperative to consider how AI applications could enhance quality of care in relation to all these interrelated matters.

AI would be implemented in social and technical contexts that are complex and diverse. For example, many residential aged care facilities have limited infrastructure capacity and care resources, which can hinder the successful implementation of innovative technologies. Thinking of these existing contexts, along with issues of sustainability, is critical for AI design and use.

We need to develop clear guidelines and regulations for the use of AI in aged care, and unambiguous definitions of care provided in residential aged care facilities.

To design and develop AI technologies that will be useful for aged care, it's important to address the main types of care provided at residential aged care facilities.

With the "ageing in place" policy, older people are encouraged to stay at home for as long as possible. When admitted to residential aged care, many older people are frail and fully dependent on staff and carers. The fact that most residents die in aged care facilities means that they also need to be equipped with end-of-life care.

Maintaining autonomy and dignity

Acknowledging the distinctive feature of care in aged care contexts from those provided at other healthcare settings has important implications for establishing guidelines, regulations and social policies of AI in aged care.

For example, the question of how to maintain the autonomy and dignity of older people is often raised but discussed in only vague terms in ethical discussions of the use of AI in aged care.

Many aged care residents experience deterioration of physical and cognitive health, which impacts their decision-making ability. This means that important decisions are often made co-jointly with residents, family and care professionals, or are just made by carers who have power of attorney. As such, we need to discuss the nexus between relational autonomy and relational care.

While AI has recently emerged in the media and political debates as a way to support aged care, we must question any form of techno-solutionism – or the idea that technology will solve all our problems.

"Care" is inescapably a collective activity, and this is critical in end-of-life decision-making. Again, with declining physical and cognitive capacity, preserving residents’ dignity may require a unique approach.

Professor Joseph Ibrahim at Monash University argues for a dignity-of-risk approach that protects residents’ rights and choices. This example helps to articulate the importance of defining clearer aims and outcomes of how AI could assist in optimising end-of-life care, providing a respectful and sensitive dying experience for all involved in care.

While AI has recently emerged in the media and political debates as a way to support aged care, we must question any form of techno-solutionism – or the idea that technology will solve all our problems.

Of course, reimagining and restructuring how we care for our older people requires an array of innovative approaches. AI technologies do bring new opportunities and can assist with the task. However, challenges about AI implementation and outcomes also abound, and we urgently need more research on its technological, social and ethical implications.

This calls for a multidisciplinary understanding of care and technology that bridges the social sciences, law and humanities, medicine, and computer science. Our response to the failures in aged care must be swift, but also multi-dimensional and evidence-based.

This article was co-authored with Kate Seear, an Australian Research Council Future Fellow, practising lawyer, and trained sociologist, based in the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society at La Trobe University.