People love creating words — in times of crisis it’s a “sick” (in the good sense) way of pulling through.

From childhood, our “linguistic life has been one willingly given over to language play” (in the words of David Crystal). In fact, scientists have recently found learning new words can stimulate exactly those same pleasure circuits in our brain as sex, gambling, drugs and eating (the pleasure-associated region called the ventral striatum).

Read more: The shelf-life of slang – what will happen to those 'democracy sausages'?

We’re leximaniacs at heart and, while the behaviour can occasionally seem dark, we can learn a thing or two by reflecting on those playful coinages that get us through “dicky” times.

Tom, Dick and Miley – in the ‘grippe’ of language play

In the past, hard times birthed playful rhymes. The 1930s Great Depression gave us playful reduplications based on Australian landmarks and towns – “Ain’t no work in Bourke”; “Everything’s wrong at Wollongong”; “Things are crook at Tallarook”.

Wherever we’re facing the possibility of being “dicky” or “Tom (and) Dick” (rhyming slang for “sick”), we take comfort in language play. It’s one thing to feel “crook”, but it’s another thing again to feel as “crook as Rookwood” (a cemetery in Sydney), or to have a “wog” (synonymous with “bug”, likely from “pollywog”, and unrelated to the Italian/Greek “wog”).

Remedies may be found in language’s abilities to translate sores into plasters, to paraphrase William Gouge’s 1631 sermon on the plague. New slang enables us to face our fears head-on — just as when the Parisians began calling a late-18th-century influenza “la grippe” to reflect the “seizing” effect it had on people. The word was subsequently taken up in British and American English.

In these times of COVID-19, there are the usual suspects: shortenings such as “sanny” (hand sanitiser) and “iso” (isolation), abbreviations such as "BCV" (before coronavirus) and WFH (working from home), also compounds “corona moaner” (the whingers) and “Zoombombing” (the intrusion into a video conference).

Plenty of nouns have been “verbed”, too — the toilet paper/pasta/tinned tomatoes have been “magpied”. Even rhyming slang has made a bit of a comeback, with Miley Cyrus lending her name to the virus (already end-clipped to “the Miley”). Some combine more than one process — “the isodesk” (or is that “the isobar”?) is where many of us are currently spending our days.

Slanguage in the coronaverse – what’s new?

What's interesting about COVID-lingo is the large number of creations that are blended expressions formed by combining two existing words. The new portmanteau then incorporates meaningful characteristics from both. Newly spawned “coronials” (corona and millennials) has the predicted baby boom in late 2020 already covered.

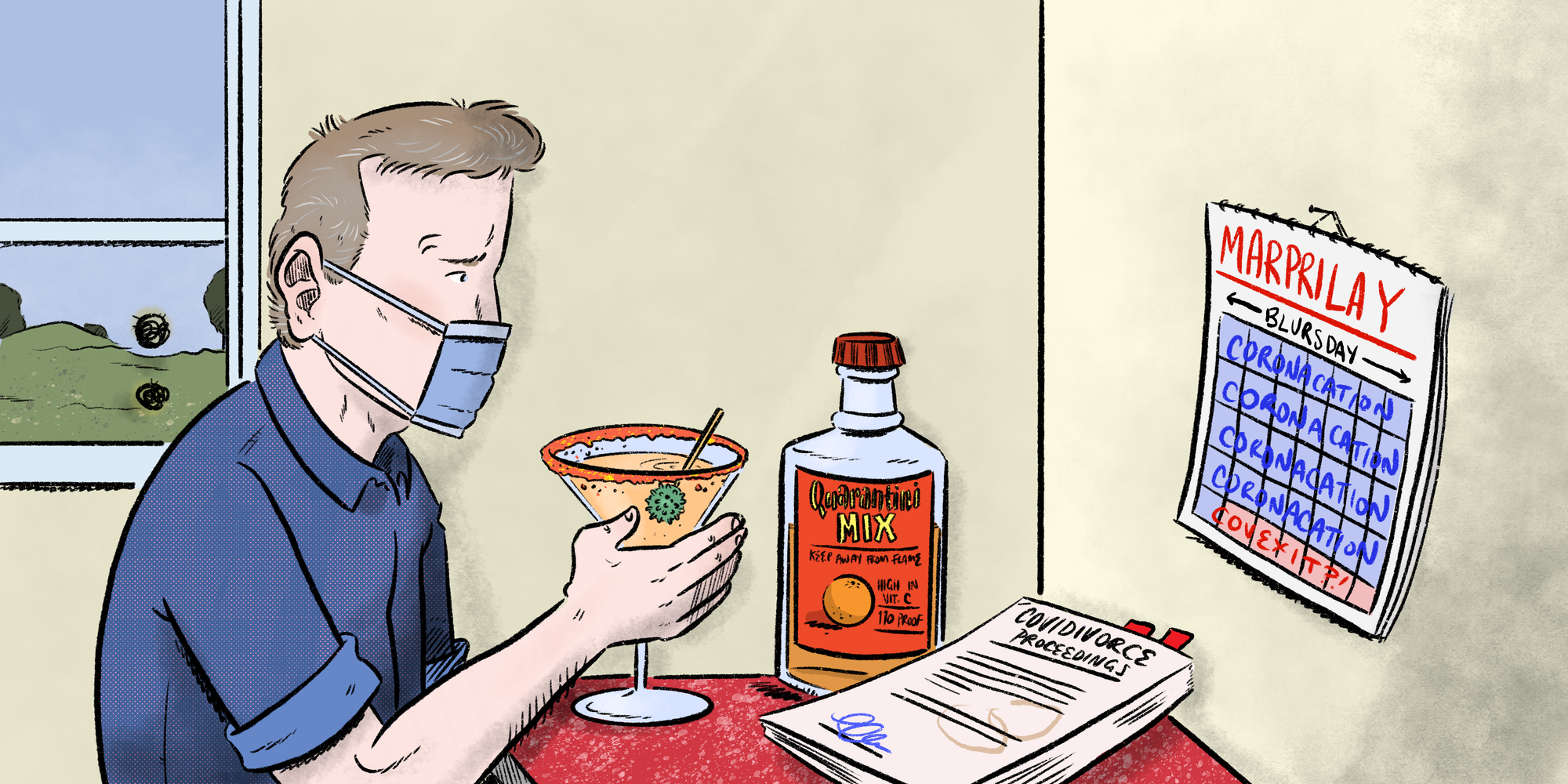

“Blursday” has been around since at least 2007, but originally described the day spent hung over — it’s now been pressed into service because no one knows what day of the week it is anymore. The official disease name itself, “COVID”, is somewhere between a blend and an acronym, because it takes in vowels to make the abbreviation pronounceable (CO from corona, VI from virus and D from disease).

'Blursday' has been around since at least 2007, but originally described the day spent hung over — it’s now been pressed into service because no one knows what day of the week it is anymore.

True, we’ve been doing this sort of thing for centuries — “flush” (flash and gush) dates from the 1500s. But it’s never been a terribly significant method of coinage. John Algeo’s study of neologisms over a 50-year period (1941-91) showed blends counting for only 5 per cent of the new words. Tony Thorne’s impressive collection of more than 100 COVID-related terms has about 34 per cent blends, and the figure increases to more than 40 per cent if we consider only slang.

Not only have blends become much more common, the nature of the mixing process has changed, too. Rather than combining splinters of words, as in “coronials”, most of these corona-inspired mixes combine full words merged with parts of others. The “quarantini” keeps the word “quarantine” intact and follows it with just a hint of “martini” (and for that extra boost to the immune system, you can rim the glass with vitamin C powder). Many of these have bubbled up over the past few weeks — “lexit” or “covexit” (the strategies around exiting lockdown and economic hardship), “coronacation” (working from home), and so on.

Humour – from the gallows to quarantimes

Humour emerges as a prevailing feature of these blends, even more so when the overlap is total. In “covidiot” (the one who ignores public health advice and probably hoards toilet paper), both “covid” and “idiot” remain intact. There’s been a flourishing of these types of blend — “covideo party”, “coronapocalypse”, “covidivorce” to name just a few.

Clearly, there's a fair bit of dark comedy in the jokes and memes that abound on the internet, and in many of these coinages, too — compounds such as “coronacoma” (for the period of shutdown, or that deliciously long quarantine sleep) and “boomer remover” (used by younger generations for the devastation of the baby boomer demographic).

Read more: Oi! We're not lazy yarners, so let’s kill the cringe and love our Aussie accent(s)

Callous, heartless, yes. But humour is often used as a means of coming to terms with the less happy aspects of our existence. People use the levity as a way of disarming anxiety and discomfort by downgrading what it is they cannot cope with.

Certainly, gallows humour has always featured large in hospital slang – diagnoses such as GOK (“God only knows”) and PFO (“pissed and fell over”). For those who have to deal with dying and death every day, it's perhaps the only way to stay sane. COVID-19 challenges us all to confront the biological limits of our own bodies – and these days, humour provides the much-needed societal safety valve.

So what will come of these creations? The vast majority will fall victim to “verbicide”, as slang expressions always do.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.