Australians like to think of themselves as living in the land of the “fair go”. Problem is, not all of us get one.

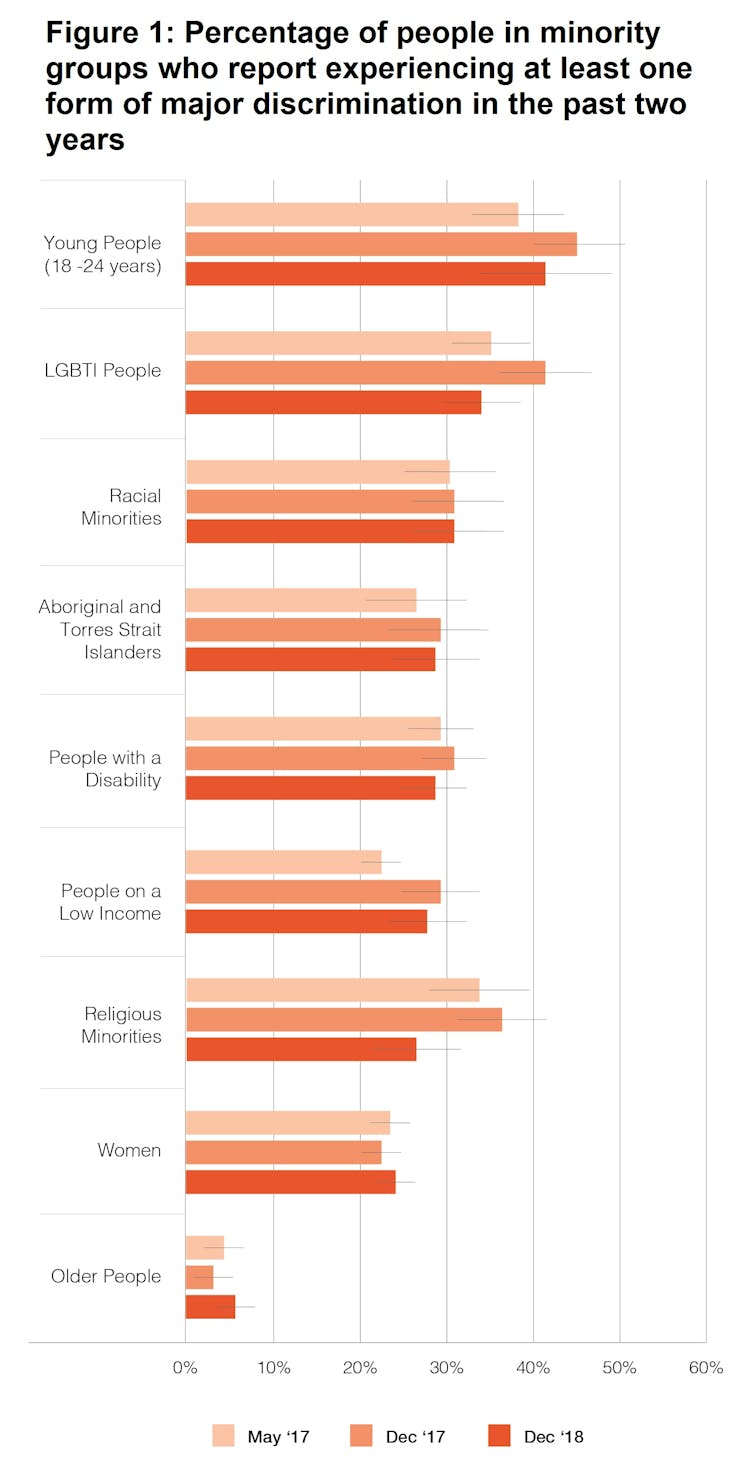

As part of a new research project, we surveyed nearly 6000 Australians over three waves between May 2017 and December 2018, and found that almost a quarter of Australians have experienced a major form of discrimination. This includes being unfairly denied a promotion or job, refused a bank loan, or discouraged from continuing education.

People under the age of 25, LGBTI people and racial minorities are most likely to report experiences of major discrimination.

Read more: Religious Discrimination Bill is a mess that risks privileging people of faith above all others

And 27 per cent of Australians have experienced other forms of “everyday” discrimination at least weekly, such as being treated with less respect, harassed, or called names.

We also found that people who have experienced discrimination have a lower sense of wellbeing and a weaker identification with Australia than those who have not.

Why social inclusion matters

The outcome of this research is a new Social Inclusion Index, released today to coincide with the launch of Inclusive Australia, an alliance of individuals and organisations seeking to promote social inclusion using techniques informed by behavioural science.

We asked participants about their views and experiences of social inclusion in Australia based on the following aspects:

- Prejudicial attitudes and experiences of discrimination

- Contact with people from minority groups

- Belonging and well-being

- Willingness to volunteer for social inclusion

- Willingness to advocate for social inclusion

Although many other surveys have focused on specific dimensions of social inclusion – such as attitudes towards immigrants and ethnic minorities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and people with disabilities – the index is unique in tracking Australia’s progress in social inclusion more broadly.

Social inclusion is the process of ensuring that all people – regardless of their race, religion, sexual orientation, age, gender or disability – are able to fully contribute to society and feel accepted.

Inclusion matters for a healthier and more economically and socially productive population. And in recent decades, governments around the world have devoted substantial attention to improving social inclusion. The World Bank has called it a “moral imperative”.

Overall, our research shows we have some way to go to become a truly inclusive nation. Australia scored somewhat above the mid-point on the index (62 out of 100), suggesting room for improvement.

Levels of prejudice and contact with minorities

To gauge the level of prejudice that Australians have towards others, we asked our participants if they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements, such as “Most politicians care too much about racial minorities” or “Women are too easily offended”.

Read more: The most important issue facing Australia? New survey sees huge spike in concern over climate change

While we found that most Australians are not highly prejudiced, a sizeable minority are.

About one in four people are highly prejudiced against religious minorities (27 per cent), racial minorities (27 per cent), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (25 per cent).

About one in five people are highly prejudiced against LGBTI people (21 per cent) and one in six against women (17 per cent). Fewer people held highly prejudiced views towards older people (4 per cent) or those with disabilities (6 per cent).

However, nearly one in three (29 per cent) people with disabilities still reported experiencing major discrimination in the past two years.

Behavioural science research has shown that contact between different groups is one of the most effective ways to cultivate empathy and reduce prejudice.

But on this, Australians also have a way to go. We found people had limited interactions with those who are different from them.

For instance, about one in five people “never” have any contact with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people or LGBTI people. One in four “never” have contact with religious minorities.

Willing to speak up

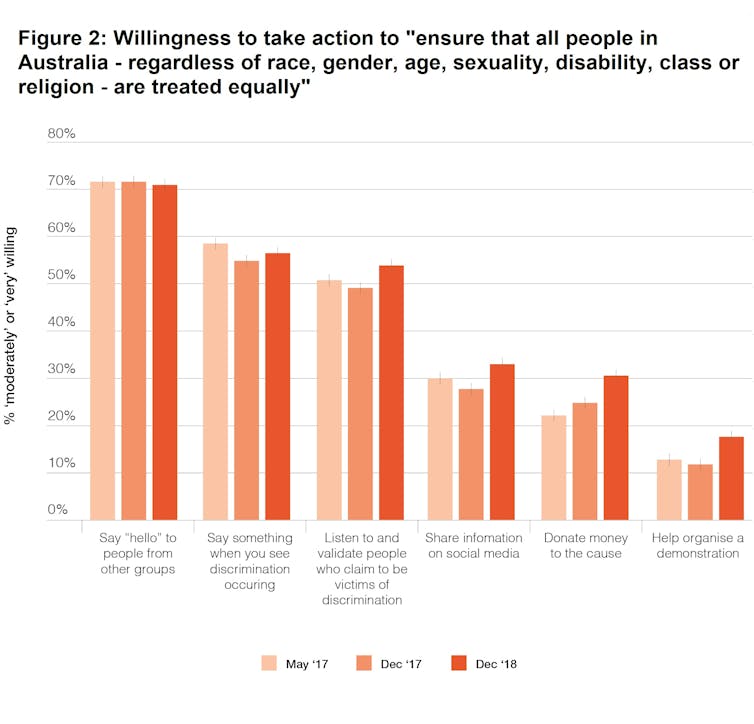

One positive finding from our research was the number of participants who were willing to take action to support social inclusion.

While most were reluctant to be involved in political action, such as demonstrations, more than half were willing to do small but important things every day to promote social inclusion.

These included saying hello to people from other groups, speaking up in the face of discrimination, and listening to and validating the stories of people from other groups.

Towards a more inclusive society

As a first step towards eliminating discrimination and prejudice, Inclusive Australia is launching an Instagram campaign to encourage people to interact with people from different groups.

Starting today, a different Australian will curate a series of posts every day on the Instagram account @_somebodydifferent.

Read more: In long-awaited response to Ruddock review, the government pushes hard on religious freedom

To counter the echo chambers of social media, in which we tend to communicate only with people who are similar to us, this account will allow followers to see posts about the everyday lives of people who may have very different backgrounds to them.

It's a small but significant step to promoting a more inclusive Australia.

Nicholas Faulkner receives research income from Inclusive Australia to his employer, Monash University, for this research. He's also received funding to his employer from various government agencies (including the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, and the Department of Justice and Community Safety) to conduct research relevant to social inclusion.

Kun Zhao receives funding from Inclusive Australia, a not-for-profit organisation seeking to improve inclusion in Australia.

Liam Smith receives funding from Inclusive Australia. He's also on the board of Inclusive Australia, a not-for-profit organisation seeking to improve inclusion in Australia.