It’s not the first time Notre-Dame de Paris has been threatened.

The Gothic cathedral in Paris, built more than 850 years ago, has withstood rioting Huguenots in 1548, had its treasures either plundered or destroyed during the French Revolution in 1793, and suffered minor damage during the liberation of Paris in August 1944.

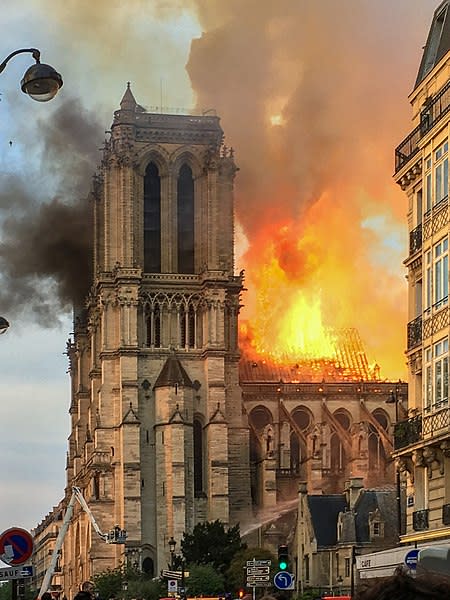

And yet it stands, even now, after fire ripped through its interior and caused the collapse of its spire on 15 April, 2019.

French President Emmanuel Macron described it as “the epicentre of our lives”, 188 years after the publication of Victor Hugo’s novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame transformed the neglected cathedral into a Paris landmark. Macron has vowed to rebuild it, and already more than $700 million has been pledged in donations to do so.

In a televised address, President Macron on Tuesday called for unity and declared the cathedral would be rebuilt within five years.

"We are rebuilders," he said. "There's a great deal to be rebuilt. And we will make the cathedral of Notre-Dame even more beautiful. We can do this, and we will mobilise everybody."

A sacred place like no other

Constant Mews is the director of Monash University’s Centre for Religious Studies. He said the building “is probably the most deeply loved and most visited monument of medieval France”, with about 12 million people a year passing through its doors.

“Whereas those who visit St Peter’s in Rome have to be ready to make a long queue before being checked by security, visitors to Notre-Dame are able to drift into a building in which they find themselves in a sacred place, unlike any other,” he says.

“Unlike Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Notre-Dame is still a place of worship. Its organ, with 8000 pipes the largest in France, combines with the remarkable acoustic of the cathedral to create a musical feast that thousands of people can appreciate.”

He says what visitors may not fully appreciate is the importance of Notre-Dame to the history of architecture.

“Throughout the early medieval period, churches had been built in the Romanesque style, namely with strong thick walls, round arches and relatively small windows – modelled on military architecture going back to the Roman period,” he says.

“The problem with this style is that churches were dark, creating a defensive space against the world. The first elements of what is misleadingly called Gothic architecture were first developed at the abbey church of Saint-Denis, now in the northern suburbs of Paris.

“The revolutionary idea underpinning the new style was that a church should be supported by its structure, rather than by its wills. The pointed arch, a style already picked up in Islamic architecture, had the capacity of sustaining a much greater weight than Romanesque buildings, which inevitably started to sag when carrying a great weight.”

“It may take decades to rebuild Notre-Dame, but in the process we may learn much more about a marvel of engineering that still has the power to take our breath away."

He says the unknown master architect of Notre-Dame dared to expand the new style of architecture to a scale not previously seen, a building 48 metres wide, and 128 metres long. Its towers, which remain standing after the fire, are 69 metres high.

“Scholars still debate the precise evolution of the cathedral, but there's now a strong possibility that its flying buttresses were central to supporting the walls of the nave from the outset of its construction – although they were only completed in the 13th century,” he says.

“These flying buttresses held up the walls, while permitting great windows to be build. We still have to learn how much of the stained glass of the cathedral has survived.”

He says that as a building, Notre-Dame set a gold standard that other Gothic cathedrals sought to surpass.

“It may take decades to rebuild Notre-Dame, but in the process we may learn much more about a marvel of engineering that still has the power to take our breath away.

“Its geometric perfection makes it the equivalent of the Parthenon in the ancient world, a statement of confidence in the power of both faith and of engineering reason.”

A symbol of national identity

Notre-Dame, which means Our Lady of Paris, sits at the eastern end of Ile de la Cite, one of two remaining natural islands in the Seine. It's a symbol of French identity and home of important religious relics, artefacts and treasures that have been saved after firefighters formed a human chain to pass them to safety.

“For French people, it is a symbol of historical continuity, because it features in many major events of French history, such as the revolution of 1879 or the liberation of Paris from Nazi occupation,” says Natalie Doyle, senior lecturer in the French studies program at Monash University.

“The spire that was destroyed by the fire was part of a controversial renovation,” she adds, “conducted in 1844 by the Romantic architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, after Victor Hugo’s novel had brought to the public’s attention the building’s state of decay.

“Ironically, the fire may inspire a more authentic re-creation of the cathedral’s true original form,” she says.

But Note-Dame isn't just a very significant building.

“Even for non-Catholics and non-French people, it's more broadly a symbol of European civilisational identity,” she says.

She says the timing of the fire was particularly striking and "forced President Macron to postpone a public declaration he was supposed to make on the 'great national debate' he called in response to the yellow-vests crisis".

“Instead, he's now pledged to rebuild the cathedral, but the question on everyone’s mind is: how?

“Macron was supposed to cut down public spending in accordance to the EU’s budgetary rules. He's already pledged money to respond to some of grievances of the yellow vests protest, which has endangered the goal of budgetary alignment. So it looks like the solution will be a public appeal for donations.”

Doyle says some people are in fact unhappy that Macron’s speech was postponed, “as French society longs for the crisis triggered by the yellow vests protests to be resolved, and are waiting for concrete steps to be taken”.

“To some French people, the fire appears as a symbol of the turmoil in which French society has been plunged, and they want answers.

“How did it happen? Incompetence? Lack of sufficient protection?" she says.

“Since 1905, the French state has been responsible for the cathedral’s upkeep, and a major program of renovation was underway, so it can be seen as a failure on the part of public authorities.

No mere mistake?

Officials have linked the fire to the cathedral’s restoration project, but “some have been quick to establish a connection with another fire on 17 March in Saint Sulpice, in another Catholic church in Paris that was found to have been the result of a criminal act”, Doyle says.

Could it have been something else other than a mistake by a tradesman?

The Saint Sulpice fire occurred after a series of cases in which Christian churches were vandalised or even desecrated.

As Doyle points out, already there are some people who are espousing conspiracy theories: that the Notre-Dame fire has come just before the holy week, and was started by Islamic terrorists as part as their “war on Christendom”.

Will the damaged cathedral be caught up in the divisions of French society, or will it, once more, play a role as symbol of the nation’s unity? It remains to be seen.