Trying to define national identity is like searching for the end of a rainbow.

It isn’t something that can be found or a place we can collectively reach; it’s something that unfolds over time and through generations. It’s also something that is contested and evokes a sense of belonging individually.

“I think national identity, like so many ways that we like to think about ourselves, is very much a generalisation of a particular moment,” says Ruth Morgan, a senior research fellow from Monash University’s School of Philosophical Historical and International Studies.

“I think different groups would have different senses of national identity and I think it means different things to different people, so it’s a very slippery topic to try and pin down.”

The idea of national identity as an abstract and ever-changing concept is not lost on Monash Professor of History Alistair Thomson, who cautions that trying to define it is both problematic and self-serving.

It is also, he says, a deeply personal concept, and so if we do try to be prescriptive and define it, we run the risk of excluding people.

“As soon as you start talking about a distinctive national identity or character, you begin to exclude and you define those who are in and those who are out and that’s a problem,” he says.

“If you tried to list all the things that Australians in the street would say were archetypically Australian, you would find contradictions. You would find fair-minded and tolerant and yet exclusive and xenophobic.

“You would find egalitarianism and yet massive inequalities. You would find this notion that we’re shaped by the bush, yet this has been an urban society since early in the nineteenth century.

“There are all these contradictions in our sense of what it is to be typically Australian, so much so that it’s probably better to get rid of that notion altogether. We are too diverse.”

In trying to articulate Australia’s identity, words and phrases and values like mateship, a fair go, the Aussie battler, egalitarianism, multiculturalism, larrikinism, and the lucky country are often cited, but do they all really apply today?

Jacinta Elston doesn’t think so.

The Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous) at Monash University describes Australia’s national identity as “complex and fractured”.

“I think a decade or two ago we could have said that we were the lucky country, we were the place of a fair go and I might have been able to go along with that, but from what I see now and what I have seen of things in society, that doesn’t ring true for me anymore.

“Now, we’ve got things like people walking down the street king-hitting somebody at 10 o’clock at night that they don’t even know – that’s not mateship. That’s not giving people a fair go, that’s bullying. We’ve got women in Australia suffering domestic violence and being killed by their partners.

“And we’ve still got refugees on Nauru and Manus Island. In our hearts and minds I think most people feel and believe this is wrong.

“Why is it so hard for us as a country to deal with this properly?”

The debates and discussions, and indeed the decisions we ultimately make around issues such as refugees and Australia Day and Indigenous recognition inevitably help to shape our national identity, as does our immigrant history, and even our landscape and seascape, and geographic position in the world. But it is not a static concept.

“Our national identity - such that it is – is an unfurling and becoming type of identity,” says Monash Vice-Chancellor, Professor Margaret Gardner.

“It’s shaped by what has come before, how that is incorporated, it’s shaped by the confluence of the profile of who makes us up now. And it’s also made up of the sorts of decisions we make.”

Melissa Castan, who is Deputy Director of the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law at Monash University, says one of the problems Australia continues to face is its difficulty in articulating the place of Indigenous Australians within its identity and that this can be traced back to how our legal, social and political structures were founded.

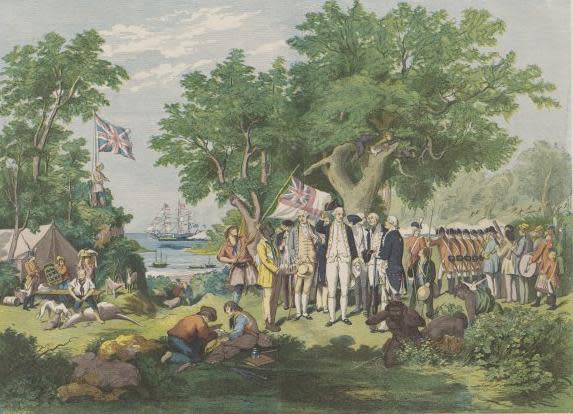

“The so-called discovery by Captain Cook and the way the British acquired the territory denied the reality of Indigenous life and culture and law and has created a fundamental flaw in our structures,” she says.

“Until we can repair those faulty foundations, we’re going to remain in this trap or this difficulty in properly relating to Indigenous identity as part of Australia’s national identity.”

Read: Celebrating and saving Indigenous Australian stories through film

She says it is possible to repair these things but that it will take good will and political willpower and “bravery on the parts of politicians”.

“Not every political leader is going to be in a position, personally or politically, where they can run with it, but eventually we’re going to get someone with a big picture kind of attitude who is capable of doing it and they’re going to drag the naysayers along with them.

“One day we will advance Australia fair, (but) we’re not quite there yet.”

Watch: Reimagining Australia Day (Episode 10: A Different Lens)