Earlier this year, we visited the Howard Springs quarantine facility in the Northern Territory, Australia’s alternative to the hotel quarantine system.

Now Victoria is set to build its own dedicated COVID-19 quarantine facility, with backing from the federal government, at a yet-to-be-confirmed location.

New quarantine hub to be built in Victoria, site yet to be confirmed https://t.co/kkbcWSUnkk— ABC News (@abcnews) 3 June, 2021

There’s much we can learn from what Howard Springs provides, in terms of how it’s staffed and its physical infrastructure. There’s a lot that’s working really well.

But if we were designing something from scratch, what could it look like? Here are some of our thoughts on how it could work.

We want to minimise people interacting

We want to minimise the number of unnecessary face-to-face interactions between staff and residents, and similarly avoid moving residents where possible.

We need to support and meet the medical needs of residents. However, where these or any other support services can be done remotely or through technology, this should be encouraged. By doing this, we reduce the number of staff at the facility.

We also want to prevent residents from physically interacting with each other. These measures reduce the chance of being exposed to the virus, and spreading it.

At Howard Springs, residents are right next to each other, in separate but neighbouring cabins. When they’re on their verandah, they can potentially come into close contact with a person on the verandah next to them. That’s not surprising, as Howard Springs was designed to accommodate miners, not as a quarantine facility.

So in a dedicated new facility, we need to design to avoid these types of close contacts, and to have clear separation of residents’ living quarters.

Howard Springs provides a separate cabin per person, in line with its original function as a mine camp. But in a newly-built facility we need to provide a variety of separate living quarters, such as separate units or apartments. For instance, we need to be able to accommodate not just single people, but family groups, especially those with young kids.

There must be no communal areas, such as shared playgrounds, which can be challenging for young kids who want to go out and play.

There must be no shared kitchens or laundry facilities. This might mean designing units with a small kitchenette or simple laundry facilities, such as a sink and a washing line.

We don’t want anything too complex that will be difficult to maintain. Maintenance means people coming in from outside, which we want to avoid.

Well-ventilated and easy to clean

Each unit needs its own ventilation system; there must be no shared ventilation between units. In Howard Springs, there’s an individual split-system air conditioning unit (to allow heating and cooling) per cabin.

Windows need to open, for ventilation. Importantly, air flow must not create a risk to others, either in other rooms or people coming to the door.

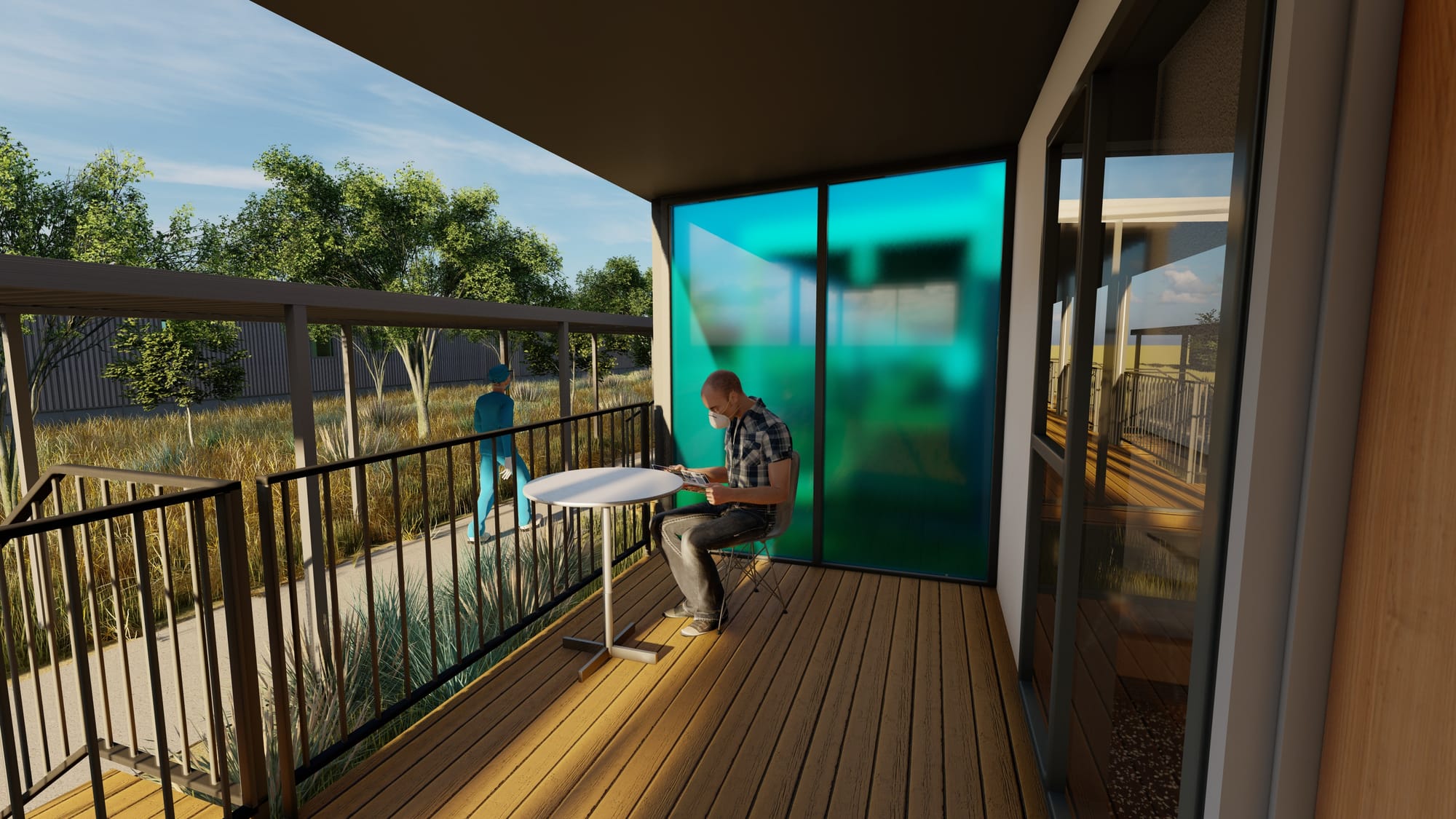

Each unit should have its own outdoor area, such as a verandah. But it needs to be covered, to allow residents to be protected from the weather (particularly for Melbourne’s climate).

Sitting on a verandah also allows residents to see other residents across the pathway, and to safely talk to them, from several metres away. If safe social contact is possible through design, that would be ideal.

Verandahs are also where all interactions between staff and residents can take place, such as swabbing of residents for COVID testing.

Units need to be easy to clean and wipe down. We need hard surfaces, like the ones we might see in a hospital, and ones that can be disinfected.

All up, the design of these units needs to be pretty simple. They need to be single-level, not double. That means residents can see each other, and staff can better keep an eye on residents.

We need an on-site clinic

We need a GP-type clinic on site. For example, there will be pregnant women who need antenatal check-ups, and people with chronic diseases who need monitoring. Then there should be protocols for transferring people to hospital, if they need higher levels of care.

We’ll need healthcare workers – primarily nurses, but also doctors. While the level of medical care is not going to be particularly complex or high, healthcare workers clearly need advanced skills in infection prevention and control. Auditing and monitoring compliance with infection control measures, including cleaning, will be important.

Like healthcare workers, security staff and cleaners also need to be trained and tested in using personal protective equipment, such as masks and gloves.

All staff need to be fully vaccinated (with two doses) of the COVID vaccine.

We need to know who’s arriving, and what they need

We need a good understanding of who’s arriving. Do they have specific medical needs? Do they have dietary requirements? We need to ask them before they arrive in Australia, so staff can prepare.

We also need clear and consistent policies about infection control, COVID-19 testing, and transfers of residents, both in and out of the facility.

We’re uniquely placed to build a dedicated, purpose-built quarantine facility, not only for this pandemic, but for future outbreaks. Including suggestions such as these will place Victoria and Australia well to meet these challenges.

This article was co-authored with Brett Mitchell, Professor of Nursing, University of Newcastle, and originally appeared on The Conversation.