Meatless burger maker Beyond Meat has just reported quarterly earnings of US$67.3 million – much better than market expectations of US$52.7 million. It is now forecasting sales of US$240 million for the 2019 year, nearly three times that of 2018.

But the company is yet to make a profit, let alone one big enough to justify its current market valuation of about US$13 billion.

Since it listed on NASDAQ in May, its shares have surged more 700 per cent. Investors’ enthusiasm reflects high hopes in the future fortunes of a company promising to put the sizzle into a meat substitute.

Interest is booming in plant-based meat substitutes and lab-grown meat alternatives. The appeal is summed up by Beyond Meat’s mission statement: “By shifting from animal to plant-based meat, we are creating one savoury solution that solves four growing issues attributed to livestock production: human health, climate change, constraints on natural resources and animal welfare.”

Read more: A vegan meat revolution is coming to global fast food chains – and it could help save the planet

How realistic is this? The data suggests not very – that meat alternatives might play a positive role but in no way are going to save the planet.

Investment appetite

Predictions about the market potential for plant-based or lab-made meat vary. A lot of it appears to be only slightly better than sheer guesswork. One prediction, by the well-known Barclays, is that the market could be worth US$140 billion, or 10 per cent of the US$1.4 trillion meat market, in the next 10 years.

It’s such projections that have fuelled investors’ appetite for companies working on ways to make plant-based protein look and taste like meat.

There’s Impossible Foods, for example, whose burger “bleeds” beetroot juice and is the meat (substitute) in Burger King’s Impossible Whopper. The privately held company has reportedly raised more than US$500 million, and is valued at US$2 billion.

Other players in the market include Nestlé, the world’s largest food company, and Tyson Foods, the world’s second-largest processor and marketer of chicken, beef and pork.

Investors are also betting on the longer-term prospect that lab-grown meat can capture the hearts and dollars of carnivores worried about the ethics and environmental sustainability of killing animals.

Feeding the world

The rationale for the importance of meat substitutes and alternatives often starts with feeding a global population projected to grow from 7.7 billion now to 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100.

Most of this growth will occur in Africa, followed by Asia. Populations elsewhere are expected to increase marginally. Europe’s will decline.

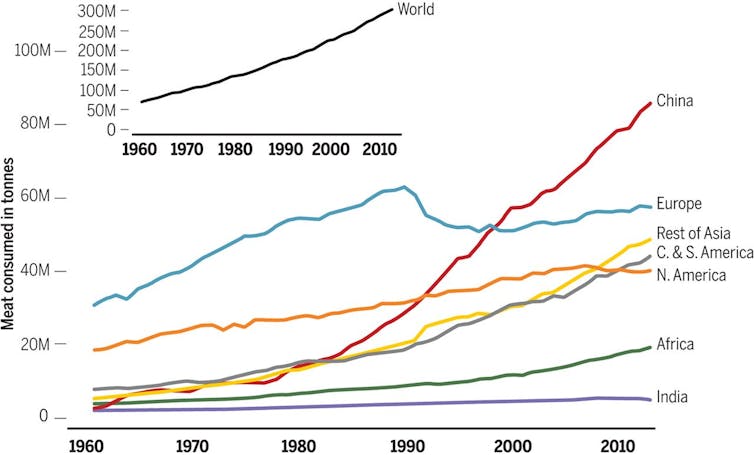

How this population growth affects meat consumption depends largely on income levels. Historical data show diets tend to become more meat-rich as wealth increases. Thus the chart below shows dramatic increases in meat consumption in China, and throughout Asia and Latin America, reflecting economic development.

Total consumption of meat (in million metric tons) in different regions and globally (inset). FAO

Only countries with cultural reasons to not eat meat, such as Hindu-majority India, are likely to buck this trend.

The fact of increasing populations in the areas most likely to also see per capita meat consumption rise is why the OECD and Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations predict meat demand in developing regions will grow at four times the rate of developed nations over the next decade.

By 2030, according to projections published by the Food and Agriculture Organisation in 2018, meat will increase by 80 per cent in low and middle incomes, under a business-as-usual scenario. By 2050, it will increase more than 200 per cent.

Can meat substitutes change the scenario? Price will make a difference. Right now consumers pay a significant premium for a plant product to taste like meat. An Impossible Whopper, for example, costs a dollar more than a standard Whopper.

But let’s say the meat substitutes can make themselve indistishuable from meat, both in taste and cost. Let’s say Barclays’ projections are accurate and meat substitutes take 10 per cent of the meat market in the next 10 years. Or even double that.

Read more: Meat consumption is changing but it's not because of vegans

It still means there are going to be more cattle, sheep, pigs and chickens on the planet than there are now. Animals will still be crucial sources of calories and protein (currently 18 per cent and 34 per cent globally), and their farming will continue to be a livelihood for hundreds of millions of smallholder farmers in Africa and Asia.

Overheated claims

In light of this, we need to have a sensible discussion about how to drive sustainability across all agriculture. This should include asking if the marketing spin of some of these companies is helping that conversation.

Impossible Foods’ founder, Pat Brown has declared: “Our mission is to completely replace animals in the food system by 2035. You laugh but we are absolutely serious about it and it’s doable.”

Really? The trends suggest it isn’t.

There’s also science to suggest it isn’t even necessary – at least from the point of view of tackling climate change. The CSIRO, for example, says Australia’s cattle and sheep industries, which produce almost 70 per cent of the nation’s agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions, could be carbon-neutral by 2030.

Read more: To reduce greenhouse gases from cows and sheep, we need to look at the big picture

Great marketing it might be, but making livestock production the great ethical and environmental bogeyman, and talking about its elimination, seems a tad overdone.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.