A year ago today, all of Australia’s work health and safety (WHS) government ministers met to discuss a ban of engineered stone to protect workers from silica dust and the deadly lung disease silicosis.

Australia's workplace ministers have agreed to implement a national ban on engineered stone, over concerns its use has led to a surge in silicosis cases among workers. https://t.co/A5GjlCH4dY— ABC News (@abcnews) December 13, 2023

The national ban will now be implemented in July this year after SafeWork Australia found no scientific evidence to support a safe threshold of silica.

In Victoria, that means employers can’t manufacture, supply, process or install any engineered stone containing crystalline silica – the new asbestos.

🚫 We’re banning engineered stone imports 🚫

Silica-related diseases have been on the rise and it’s our job to do what we can to protect workers' lives - and today we’ve done just that. pic.twitter.com/h3uaS6TSio— Tony Burke (@Tony_Burke) December 13, 2023

However, that doesn’t mean the issue is over. Monash researchers, who are at the global forefront of silicosis research, warn that it’s only the beginning.

Associate Professor Jane Bourke and her team at Monash are developing research programs for non-invasive, early detection of silicosis and new drugs to treat it.

These scientists are also passionate advocates for silicosis sufferers, and for better workplace safety in industries beyond stone-cutting and installation – such as tunnelling, quarrying and mining.

“The recent increase in Australian workers diagnosed with silicosis has been a huge concern,” says Associate Professor Bourke, “and there are people who should be or will be diagnosed, but haven't been yet.

Australia now has one of the highest rates of silicosis in the world, with silicosis-related breaches being flagged in workplaces across the country.

Watch #60Mins on @9Now pic.twitter.com/SPPpKDgGoN— 60 Minutes Australia (@60Mins) February 19, 2023

“There are more than 500,000 silica-exposed workers in other industries – a hundred times more than engineered stone workers. It’s just that a lower proportion of them either have silicosis now, or remain at risk. They’re in industries including construction, mining, quarrying, and manufacturing. The challenges in identifying those people still remain.”

This month, the company Newmont reported to a New South Wales regulator that two workers from its Cadia gold mine, near Orange in New South Wales, have early-stage silicosis.

Currently, the best way to screen for silicosis is a CT scan, but this requires a visit to the hospital. But with so many potential workers with silicosis outside of stone-cutters, the volume of people to scan isn’t realistic – the cost to do so might not outweigh the benefit.

“For a larger group of workers, we need a more economic and convenient way to screen large numbers of workers, and to make sure that they don't slip through the cracks,” Associate Professor Bourke says.

The first reported case of engineered stone-induced silicosis in Australia was in 2015, and within seven years, more than 600 cases were identified. An ACTU-commissioned report from Curtin University predicts more than 100,000 cases of silicosis across Australia if effective screening and diagnosis of workers across all dust-prone industries can be achieved.

Monash-led research by Dr Ryan Hoy and Emeritus Professor Malcolm Sim AM has previously shown that silicosis affects an estimated one in four Victorian engineered stoneworkers.

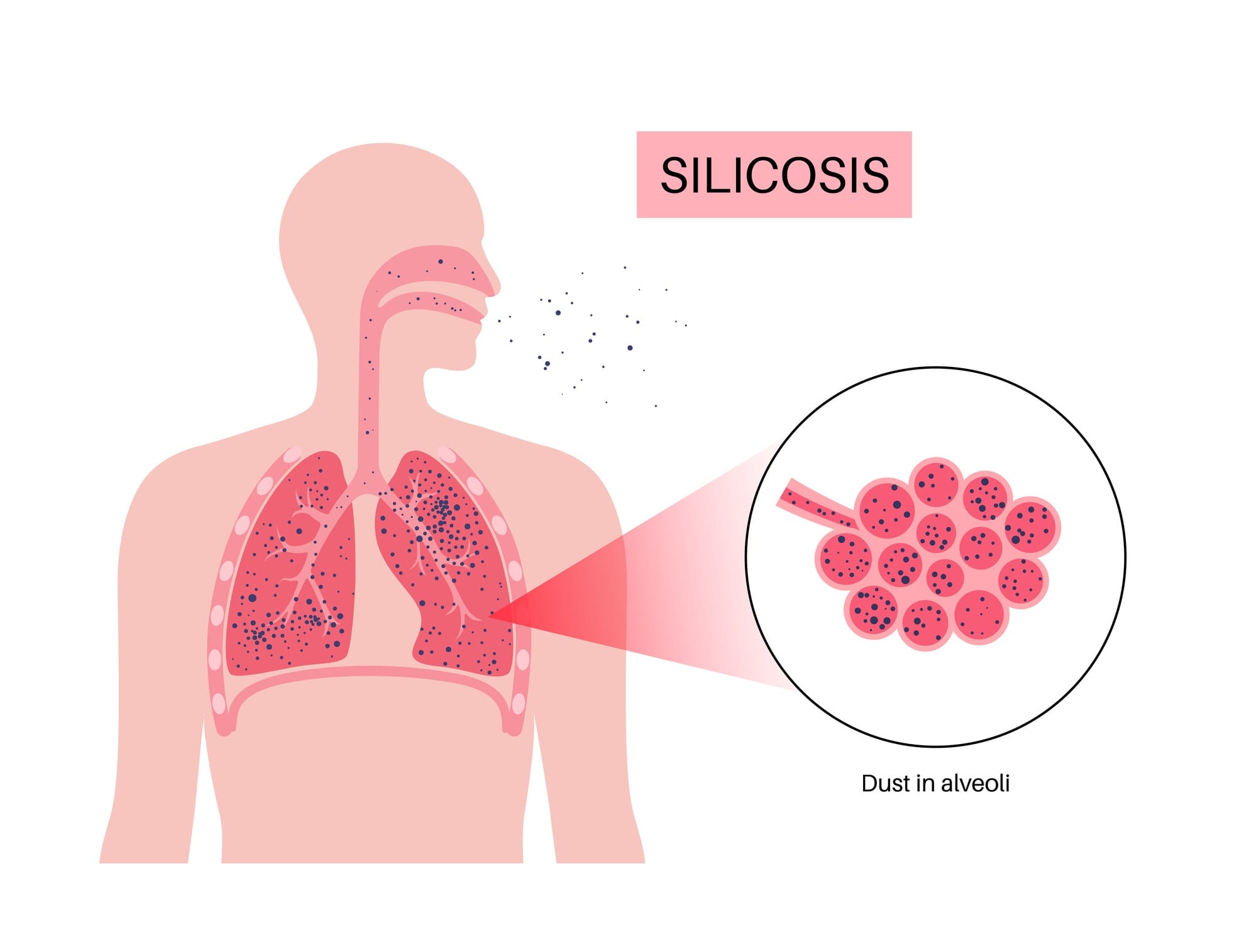

The cause is exposure to crystalline silica dust generated when engineered stone benchtops are cut, crushed, drilled or polished.

The silica particles are so small that they lodge deep in the lungs and cause inflammation and irreversible scarring that ultimately results in declining lung function. There’s no cure.

“This is a material that’s just such high-risk that it was indefensible to let people keep working with it,” says Associate Professor Bourke.

The Bourke Laboratory specialises in respiratory pharmacology, finding new drug targets for lung diseases, within the Biomedicine Discovery Institute and the Department of Pharmacology.

The Bourke lab’s team of Dr Paris Papagianis, Dr Simon Royce and PhD student Claudia Sim are beginning a trial to look for chemical markers in the breath of people with silicosis. A second project will test drugs that may help lung scarring.

“We collect exhaled breath from those people with silicosis and look at chemicals in the breath, called volatile organic compounds,” says Dr Papagianis. “Then we try to associate which of these chemicals on the breath could indicate someone with silicosis disease, compared to a healthy age-matched individual.”

This is called “breathomics”.

“We'll be able to process all the chemicals that can be detected, and then see which ones are either downregulated or upregulated in disease,” Dr Papagianis says.

“The aim is to use the findings to screen workers at their worksites, no matter where that is. No one has made profiles for silicosis in this way before, and having a non-invasive, simple test that’s cheap and mobile for screening of thousands of people is seen as the next critical next step.”

Through Claudia Sim’s research, the team has already found proteins unique to silicosis in lung fluid, rather than breath, from the same people. These findings have the potential to identify new therapeutic targets for silicosis.

To support this research, Sim has developed a novel way to test potential drugs in silica-treated human tissue to mimic the environment in the silicotic lung.

The researchers are also working alongside patient advocate Joanna McNeill, who was diagnosed with silicosis in 2019 after working in office administration at a rock quarry in outer Melbourne.

“This is a life sentence for me, and I don't even know when my time’s up.”

Thirty-four year-old mother of two Joanna McNeill never expected she would become the face of a campaign to protect workers' rights, after she contracted silicosis at work. @alicemonfries #9News pic.twitter.com/jmaFOXL2GH— 9News Sydney (@9NewsSyd) February 8, 2021

While still caring for her two young children, she’s now unable to work, and spends a lot of time in hospital because she’s vulnerable to infections. Ms McNeill helped lead an Australian Workers’ Union campaign in 2021.

“There was heavy involvement in safety [at the quarry],” she tells Lens, “but there was never even discussion about crystalline silica. For me, it was a massive shock because of all the safety stuff that I was involved in. How did I not know about it?”

She says there’s much work still to be done.

“People are still naive to it. Or they just want to not believe this is real. Mining, tunnelling, all that. I just think people are really complacent, and I think we need to talk about it heaps more. I think it needs to be in all the schools. We know what asbestos is, right? We need to get this into children so the generation changes.”

The high number of silicosis cases detected in Australia follows the recent rigorous health screening in the stone benchtop industry. The rest of the world is catching up.

“Sweden doesn’t yet have mandatory screening,” Associate Professor Bourke says. “The UK doesn't have it. Even though the first cases were reported in Israel way back in 2012, the new case series that’s emerged in California confirms that silicosis in engineered stone workers (and other industries) will remain a global issue for years to come.

“Improved and ongoing worker awareness and medical surveillance is the key,” she says.

A new WorkSafe campaign this month, in Victoria, is focused on reaching workers working with engineered stone, including those in regional communities, and will be translated for culturally and linguistically-diverse communities heavily involved in working with dust – and not just the stonecutters.