Children and youth have largely been spared the direct health effects of the COVID-19, but that obscures a huge part of the story. Mitigation measures as the pandemic rages push children into vulnerable positions that put them at risk of becoming seriously impacted.

Indeed, the effects will be unequal both between and within countries. The United Nations has already painted a grim picture of how the pandemic threatens the livelihood of children and youth around the world, while reversing the progress made on their welfare.

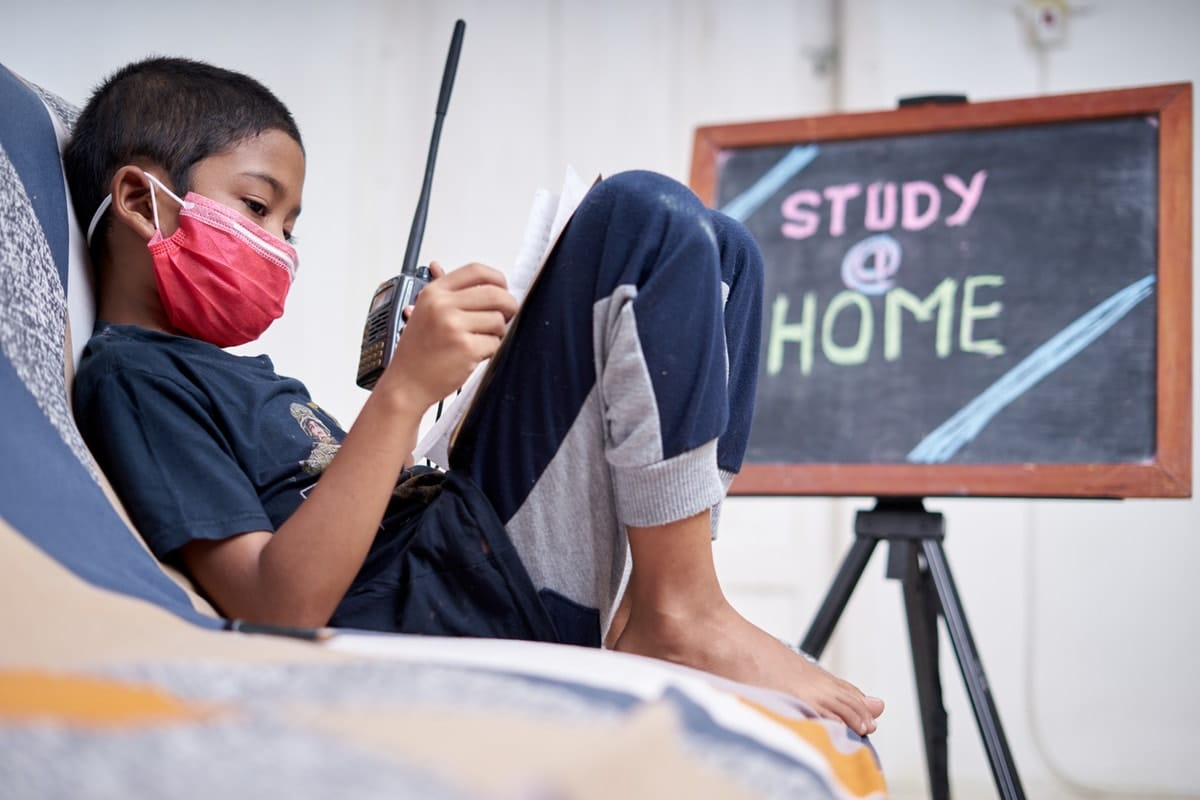

Lockdown policies implemented by countries to contain the virus have adversely affected children in terms of educational access. With almost 195 countries having partially or fully closed schools, more than 1.57 billion students, or 91 per cent, of children across the globe are forced to study from home.

Consequently, distance learning is the only solution, meaning devices and an internet connection are essential. However, just 30 per cent of low-income countries are preparing for national distance-learning platforms in response to the social distancing restrictions.

The intersection of existing vulnerabilities and the scavenging effect of the pandemic could be worse in developing and/or conflict-affected countries.

In Africa, low broadband penetration, compounded by high cost and over-concentration in urban areas, is threatening to further widen the education inequality gap. In Indonesia, the lockdown policy is impacting children in households struggling to secure income, as well as those losing jobs. In the Philippines, mistreatment of children has been reported.

The COVID-19-driven exacerbation of education inequalities will have a telling effect on human capacity development in regions that already have the lowest human development indicators. With poor health systems to contain the virus, and delayed responses at the initial stage of the outbreak, developing countries are likely to prioritise measures to restrain further spread. This way, support systems for children’s protection in times of the pandemic risk being overlooked.

Domestic violence and educational burden for Indonesian children

Human Rights Watch reported that with many parents and caregivers suffering job losses and income shortcomings, the children are more at risk of domestic violence, sexual exploitation, teenage pregnancy, and child marriage. For families lucky enough to secure jobs by working from home, the parents’ increasing stress level of navigating work, house chores, and home-schooling their children gives rise to domestic abuse to their children.

Concerns about finances, loneliness and isolation contributed to physical (spanking or slapping) and psychological (yelling, screaming and shouting) abuse of 407 children in Indonesian households from 2 March to 25 April.

There are at least 71.7 million informal workers – or 56.7 per cent of the total workforce – in Indonesia, with the average income of about IDR16,250,958 (A$1625) per year. This line of jobs, being dependent on the mobility of the now working-from-home formal workers, is the sector worst-hit by the COVID-19 lockdown and social distancing policies.

Distress brought on by the loss of these already low-paid jobs is exacerbating the possibility of both physical and emotional violence towards children.

Distress brought on by the loss of these already low-paid jobs is exacerbating the possibility of both physical and emotional violence towards children.

Children in Indonesia face significant challenges in adapting to learning from home. Teachers with little understanding of technology are often ill-equipped for the distance learning system, leading them to set students too many assignments, rather than teaching.

Assignment overload, combined with the inability to consult their educators on subjects that require adult supervision, leads to depression and emotional fatigue among children.

The Indonesian Commission for Children Protection (KPAI) received at least 51 complaints from parents regarding the excessive amount of homework their children have been set since the implementation of home learning. Adjusting to online education in these times could take a longer-term toll on children’s mental wellbeing.

Juveniles dealing with the law in the Philippines

While the Philippines is, like most countries, doing its best to control the spread of COVID-19, several human rights groups and international organisations are raising concerns about some of its drastic measures.

As part of the Philippines’ “enhanced community quarantine measures”, the country has been strictly enforcing a nationwide curfew, with about 30,000 violators reportedly arrested as part of the 126,302 lockdown and curfew violations across the country over 32 days.

The inhumane treatment of quarantine violators has sparked human rights and child rights concerns after several posts on social media went viral. In three such videos, some “violators”, mainly children, were squeezed into a mobile dog cage; others were forced to sit for hours under the high-noon sun; and children were placed in a coffin.

Human Rights Watch has reported that seven of eight young boys and girls who violated the curfew were forcibly given a haircut, while one who resisted arrest was denuded before being released. These apparently militaristic pandemic mitigation measures violate the fundamental rights of children, and humans in general – the right to dignity and respect by avoiding inhumane or degrading punishment.

As a signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), the Philippines is duty-bound to respect and observe the rights of every child.

In addition, under the Philippine Republic Act 9344 as amended by Republic Act 10630, otherwise known as the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act, “curfew and ordinances are issued for the protection of children”. Hence, “no punishment shall be imposed on children for their violations. They shall instead be brought to their residence or to any barangay [village] official to be released to the custody of their parents and provided with appropriate interventions.”

This concerning treatment of young curfew violators in the Philippines could potentially worsen, particularly since the country’s enhanced community quarantine measures were extended in the capital and certain major regions until 15 May.

Adding to this concern is President Rodrigo Duterte’s command to law enforcers that “if there are troubles, ... shoot them dead”. Considering the administration’s infamous record on its “war on drugs” that have cost the lives of juveniles, this appears a warning to everyone, including children, to not disrupt the measures during the extended lockdown.

Youths in a post-conflict environment: the African experience

As many African countries migrate learning online, an examination of the continent's internet penetration rate is telling. The World Bank put Africa's broadband penetration rate, including 3G and 4G, at 25 per cent in 2018, the lowest in the world. In 2019, Africa had both the lowest rates of households with internet access at home (17.8 per cent), and households with a computer (10.7 per cent), according to the International Telecommunication Union.

The effects of the digital divide have already been felt across Africa. In Ghana, the nationwide closure of schools on 16 March, and the digital divide compounded by erratic power supply, is taking a toll on children's education. The West African Senior School Certificate Examination, a standardised test taken by final-year senior high school students across five West African countries (Ghana, Nigeria, Liberia, Gambia and Sierra Leone) in May/June has been suspended indefinitely. The exorbitant cost of internet connection means few children can access online tutoring.

The situation could be shattering for children in war-affected environments and those living in camps.

In Uganda, for instance, it’s estimated that about 1.5 million children are in need of humanitarian assistance, as a staggering 58 per cent of the refugee population who fled conflicts in South Sudan, Burundi and DRC are minors.

Squalid camp conditions that make social distancing impossible could cause a repeat of Goma, should the virus hit the camps. Already, due to insufficient funds, the UN World Food Programme in east and central Africa announced a 30 per cent cut to the food rations it distributes to refugees; this came into effect on 1 April.

The children’s program will be further affected as funding cuts hit the development community. There are reported frustrations among the humanitarian community over unredeemed pledges to humanitarian interventions in Africa.

As COVID-19 pushes developed countries to the brink of economic recession, they’re more likely to focus on reviving their economies post-pandemic. This could reverse the gains made in combating child poverty, child mortality, health risks, and education access as funding dries up.

Global action is urgently need

It’s likely, particularly from the perspective of developing nations, the pandemic will increase the risk to children’s security.

In countries where most households earn an income through menial jobs, a lockdown could have far-reaching consequences on children’s wellbeing and add to malnourishment, especially in post-conflict societies.

One goal out of COVID-19 should be to improve our ability to swiftly respond and minimise vulnerabilities in future health emergencies. This starts with investing in today's children, and requires action at both national and international and national levels.