For the past few years, it’s been impossible to escape the impact of inflation. Meeting our most basic needs – such as food, housing and healthcare – now costs significantly more, and wage increases haven’t kept up.

There are signs relief could be on the horizon. Inflation has fallen to its lowest levels since January 2022.

But Australia now also finds itself in the midst of an economic downturn, putting further pressure on households.

Read more: ‘What Happens Next?’: Can We Take a Bite Out of Food Insecurity?

Rising prices have an obvious negative impact on our financial health. But they can also have a profound effect on our physical and mental wellbeing, which is often overlooked.

Australians may continue to feel the health effects of high inflation for quite some time.

It’s costing more to live well

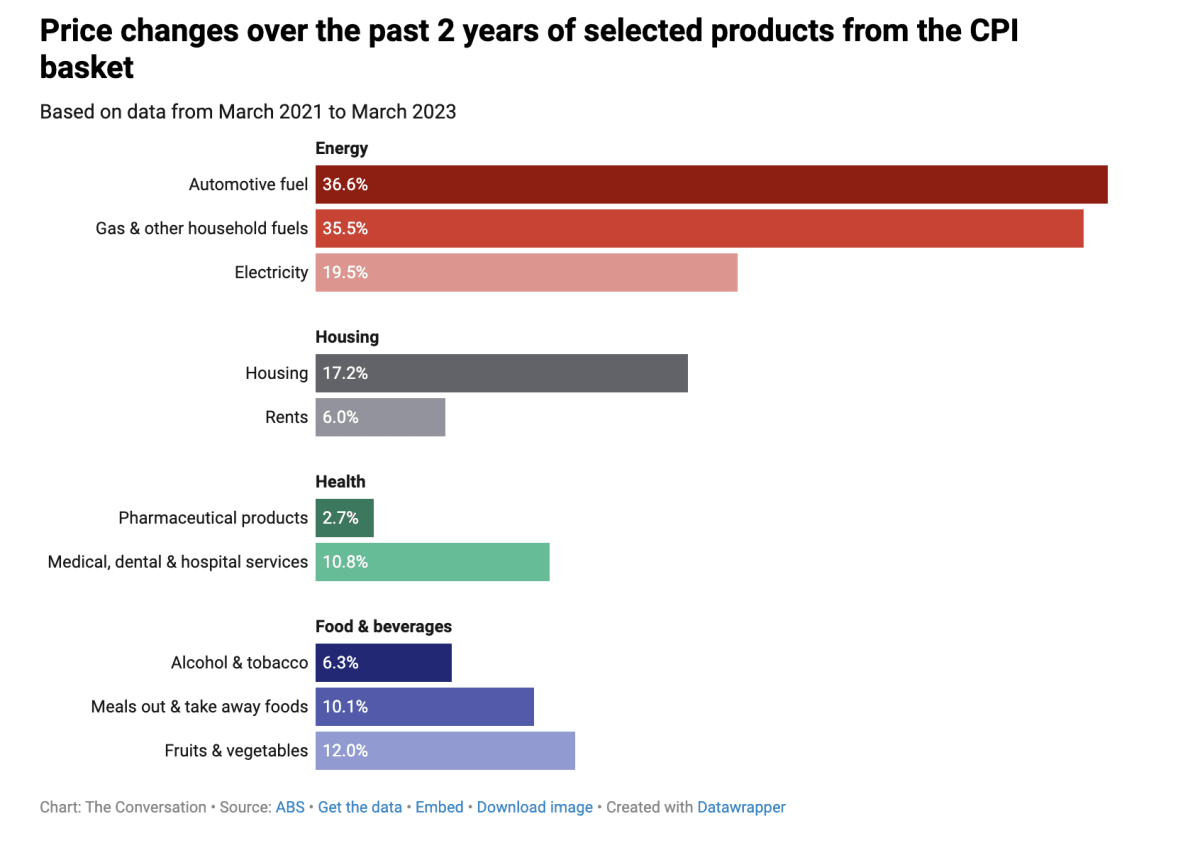

Between March 2021 and March 2023, the price of goods and services rose substantially, marking a period of high inflation.

Worryingly, the prices of basic needs that are important for staying healthy – nutritious food, healthcare, housing and utilities – rose between 11% and 36%.

Who is affected the most?

Higher prices on essentials are virtually impossible to dodge, but they impact certain groups of people more than others.

Wealthier households have managed their higher expenses by cutting back on discretionary spending and dipping into savings.

However, lower-income households spend a much larger portion of their income on housing and other essentials.

Without a savings buffer, these households experience severe financial strain and poor health outcomes.

Financial stress affects our health

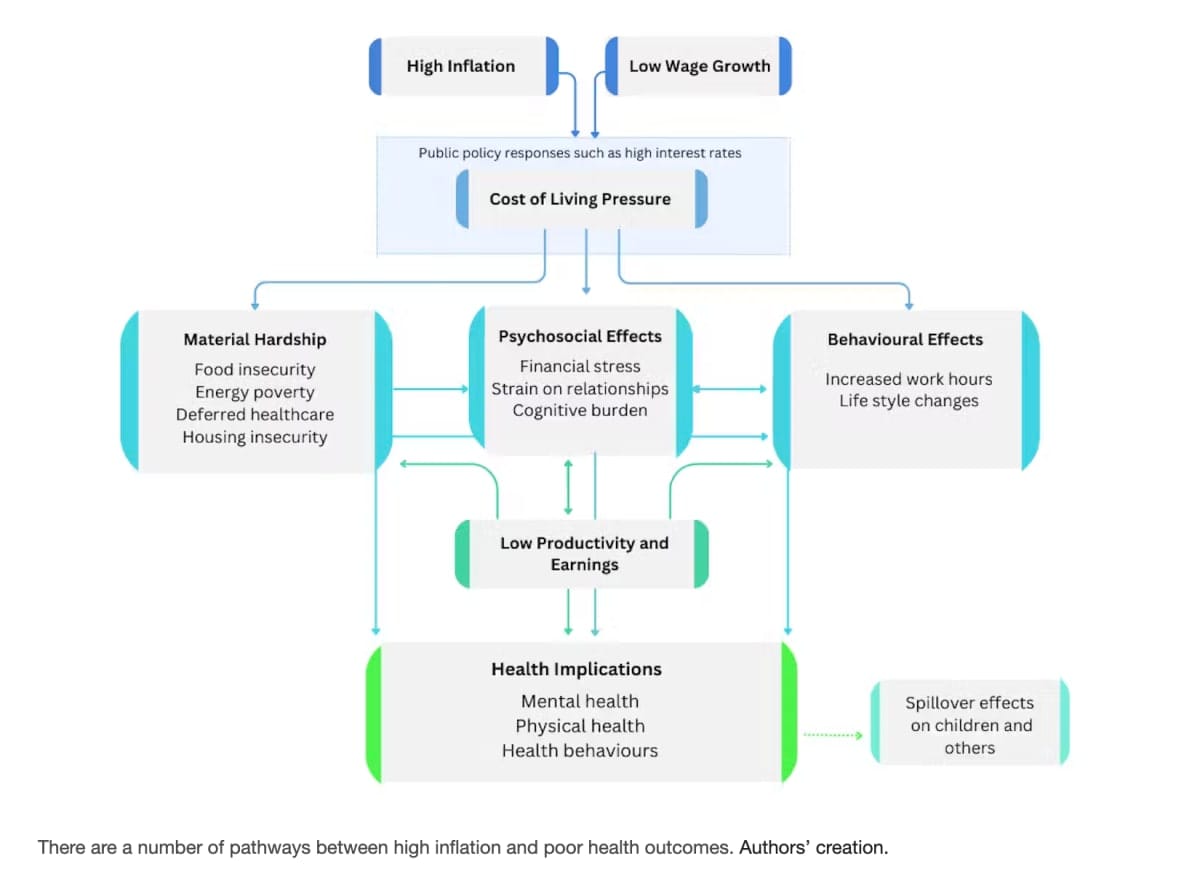

Our research shows that high inflation has a range of effects on people’s health.

These effects fall into three main groups – material hardship, psychosocial, and behavioural.

1. Material hardship

People facing material hardship can’t meet their basic needs because they can’t afford to pay for them.

Material hardship can present itself in a variety of ways:

- Food insecurity – not getting adequate nutrition

- Energy poverty – struggling to pay for electricity and gas

- Deferred healthcare – putting off medical treatment

- Housing insecurity – struggling to find a stable place to live.

Between August 2022 and February 2023, when inflation hit its highest levels in 33 years, more than half (53%) of surveyed Australians reported struggling to afford their basic needs.

Finding ourselves in this situation can have far-reaching implications for our health.

For example, food insecurity is linked to an increased risk of poor nutrition, obesity and chronic illness, as households facing cost-of-living pressures shift towards cheaper, lower-quality food options.

Energy poverty is linked to physical and mental health problems as people struggle to keep warm in winter, and cool in the summer.

Delaying healthcare increases the risk of facing severe health problems, staying in hospital for longer, and being admitted to the emergency department. This isn’t just worse for individuals, it’s also far more costly for our healthcare system.

2. Psychosocial effects

Psychosocial effects are the ways in which cost-of-living pressures impact our mind and social relationships.

Difficulties in meeting our basic needs are strongly associated with increased levels of psychological distress, including symptoms of anxiety and depression.

This impact can worsen over time if individuals experience sustained financial stress.

By undermining our ability to work well, the psychosocial effects of prolonged financial stress can initiate a “vicious cycle”, leading to reduced productivity and lower earnings.

Financial stress can also have a detrimental impact on spousal relationships, which can affect the mental health of other household members such as children.

3. Behavioural effects

Cost-of-living pressures can also cause a number of changes in the way we behave.

For many, these pressures have become a reason to work longer hours and gain additional income.

Last year, Australians collectively worked 4.6% longer, an extra 86 million hours.

But working longer hours reduces people’s overall health, especially among parents of young children facing greater time constraints.

It also leaves less time for activities that help to keep people healthy, such as getting regular exercise, and cooking healthy meals.

How can policymakers respond?

In theory, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s primary tool for combating inflation – raising interest rates – should help. By reducing aggregate spending in the economy, it’s designed to put downward pressure on prices.

But by bluntly increasing the cost of borrowing, it also puts significant short-term financial pressure on both lower-income mortgage-holders and renters.

Better acknowledgement of this fact, and of inflation’s broader impact on people’s physical and mental health, would be a great start.

When formulating policy responses to high inflation, governments could factor health and wellbeing impacts into their assessment of the trade-offs between alternative policy responses.

This could help minimise any policy’s long-term negative health consequences and its impact on the healthcare system.

Policymakers could also focus on making sure affordable and timely access to healthcare, especially mental health support, is made available to those most vulnerable to cost-of-living pressures.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.