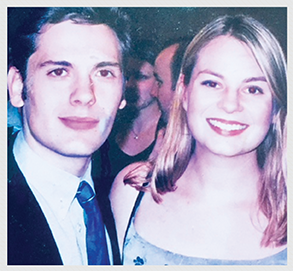

Alan and Jane Oppenheim

There’s a yellow pencil case at the beginning of the life – and love story – of Jane and Alan Oppenheim, two Monash science undergraduates in the late 1970s who have gone on to head one of Australia’s most successful skincare companies – Ego Pharmaceuticals.

As Alan tells it, they exchanged their first words when Jane enquired what the initial ‘A’ stood for in the bold lettering he’d used on it. But Jane hadn’t just noticed the pencil case. Its owner had an infectious sense of humour, and “he was tall, dark and handsome”, she says.

The two were part of a larger group of Monash science students – a studious bunch who treated university like a 9-to-5 job and took breaks at the Hargrave Cafe. “They had a relatively new thing at the time, which was carrot cake,” remembers Jane – a morsel as delicious as it was unfamiliar. “I actually thought I was eating currant cake for an entire term,” Alan says.

Alan also fondly remembers many happy hours listening to Monty Python in the Union Building’s record library, and his penchant for the theatrical extended beyond campus. He bought his friends memberships for the Melbourne Theatre Company (MTC) and, while it was sometimes a hassle to round up the money, there was a distinct upside. “I soon realised I was sitting next to Alan at every performance,” says Jane.

The two, who shared a love of maths – bonding particularly over star lecturer Andrew Prentice’s efforts to wake up his 9am applied maths class with his trademark laconic humour – slowly became a couple. A few years after both graduating with honours, they married, in 1983.

Alan joined his parents’ company in 1981, implementing, with his brother, Ego Pharmaceuticals’ first computer system – a task with a high degree of difficulty given the term ‘PC’ had barely been coined. Meanwhile, Jane was completing her PhD with such determination that she wore out every chair in Alan’s late grandmother’s dining set in the process.

Through her doctorate, co-supervised by Professor Ian Rae, Jane was at the forefront of a new movement in science driven by the sequencing of the human genome peptide creation. And she quickly found work with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, working in immunology.

That grounding, she says, was invaluable in her subsequent role at Ego, where she joined Alan in 1988 to head R&D. Together the couple have built upon the values introduced by Alan’s parents, bringing scientific rigour and innovation to all facets of the company, from product development to manufacturing processes and internal relations.

With Jane (as scientific and operations director) essentially overseeing supply, and Alan (as managing director) handling demand, the company today has more than 600 employees, and offices in 30 cities across 12 nations. A slew of industry awards were received this year, with Jane winning the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering’s Clunies Ross Entrepreneur of the Year Award, recognising her achievements in scientific commercialisation.

With their professional and personal lives inextricably linked, the two insist they do find time to wind down without talking shop. They’ve even maintained an interest in the MTC. “Jane has just booked another play,” Alan says. “A season’s pass,” adds Jane.

Teng Chye and Yvonne Khoo

Teng Chye and Yvonne Khoo grew up near each other in Singapore, but it wasn’t until they were both students at Monash in the 1970s that they met – volunteering on a newsletter for the Singapore Students’ Association of Victoria at Union Hall.

Teng Chye was an engineering student, and Yvonne was studying English and sociology, but they bonded while compiling activities for expats and news from home. “One thing led to another and soon we were studying together and going for dances,” says Teng Chye.

Romance was blossoming, but with Yvonne living “with the nuns” in a Catholic girls’ hostel in Chadstone and Teng Chye residing at the all-male Mannix College, finding time to spend together outside of university hours was a challenge.

So as the new co-ed Richardson Hall opened its doors on campus, the two became among its first residents and “life got much closer”, says Teng Chye. “And more distracting,” adds Yvonne.

The couple have fond memories of that time and were thrilled when, on returning to Monash last year for the Global Leaders’ Summit, they found a framed photo of themselves with their class of 1974 still hanging in Richardson Hall’s common room. They also took delight in regaling current-day boarders with stories of the era.

“Standing just behind us in the photo is a student with very long hair about to tip a pitcher of beer over his friend’s head, and they wanted to know if he actually emptied it,” says Yvonne. “The students today seem to be very serious and well-behaved compared to us,” observes Teng Chye.

The couple, who have two daughters and are celebrating 40 years of marriage this year, moved back to Singapore after graduating in 1974. Being a Colombo Plan scholar (an Australian government scholarship for students to strengthen relations between Asia and the Pacific), Teng Chye was obliged to work for the government and, after completing military service, began what would become an illustrious career in urban infrastructure and development.

Today, as executive director of Singapore’s Centre for Liveable Cities, he still enjoys a connection with Monash, particularly through CRC for Water Sensitive Cities CEO Professor Tony Wong, and the University’s Sustainable Development Institute chaired by Professor John Thwaites.

Yvonne became a teacher of English and literature and, to this day, takes special delight when her students go on to further study at Monash. “When I tell them I studied there, they say ‘Which campus?’, and I say ‘What do you mean?’. There was only one campus when we were there and it was rural. We used to call it ‘the farm’.”

On their return, Teng Chye couldn’t help casting a professional eye over the significant changes to the Clayton campus since those student days.

“The architecture, the landscaping, it’s really like a whole new town,” he says. “It’s very well done.”

Xiang Ao and Li Zhaoyuan

Ao and Li Zhaoyuan didn’t meet at Monash, but through Monash, signing up as undergraduates at China’s Central South University for the 2+2 Bachelor of Engineering program – an initiative that provides education at Monash and partner institutions, and qualifications from both.

But it was during their two years at Monash from 2009 that their relationship flourished. Despite Xiang specialising in polymers and Li in metallurgy, the young couple shared common subjects and friends, living in share houses with fellow students from a variety of countries including Malaysia, India, Indonesia and the Maldives.

“What we loved about Monash was its diversity among the students,” Xiang says. And what was best about that, she says, was the food. “Definitely the food. Everybody enjoyed cooking their home dishes and sharing.”

Xiang says she and Li were attracted to the 2+2 program for the opportunity to study at Monash – “renowned for excellence in engineering” – and the options it would open up in both China and Australia.

It was, she says, better than her expectations – and more challenging. “It was harder than the first two years in China because you had to be more independent, but then in fourth year it encouraged you to think about your career,” she says.

The vocational focus also prepared them well for life outside university, with both Xiang and Li’s first jobs related closely to their final-year projects – Xiang’s in water treatment and Li’s with Iluka Resources. Li’s took him to Western Australia, but the pair maintained their strong bond. And, 10 years on, the now-married couple calls Melbourne home, with Xiang working in the energy sector and Li in management consulting. “We are definitely here to stay,” Xiang says.

Gary Chan and Amy Tam

As international students from Hong Kong, Gary Chan and Amy Tam knew no one when they met as undergraduate students in their economics tutorial nearly 10 years ago.

Connecting quickly at an intellectual level, the commerce students began to spend more time together after class, staying on campus to study, eat and play – a particular favourite being badminton in the sports centre.

As the months passed, their study and sports sessions turned into a friendship, and then more. And their relationship had plenty of time to flourish – not only on campus. They both lived in the CBD – Amy at a student hostel, and Gary at a homestay, before moving out together in their final year – and they spent many hours commuting together by tram, train and bus to the Clayton campus. “We talked a lot,” Gary says.

That journey was one happily relived last November as the pair again travelled out to Monash to have their wedding photos taken.

Now based in Hong Kong (where they returned after graduation to be closer to their families), Gary and Amy were thrilled when University management agreed to their photo shoot at Robert Blackwood Hall. “We thought of Monash because, along with our apartment in our final year, it was our home,” Amy says. “And it was so nice – they opened the hall and turned the lights on just for us.”

Gary, who now works as a financial planner, and Amy, who’s in administration and marketing with her family business, say Monash provided some of the happiest memories of their lives. “We studied together, took care of each other, grew up and became independent,” he says.

Dr Danielle Esler and Dr David Mitchell

It was 1999, and Danielle Esler, recently returned to full-time medical studies at Monash after a research year, was feeling a little low in the depths of a cold Melbourne winter when she met David Mitchell in a student lounge in The Alfred hospital basement.

There, they hatched a plan to lift her spirits by skipping classes for a day to go skiing. “We tried to recruit a group of people to go, but they all piked because they were afraid of wagging and it affecting their marks,” Danielle says. “So it ended up being just the two of us.”

The pair got to know each other one on one, becoming fast friends and spending more and more time together: in study groups, travelling, even volunteering at a refugee camp on the Thailand–Myanmar border where they lived in a hut. “Pre-dating intimacy,” Danielle says.

By 2002 the friendship blossomed into romance and, looking back, while neither can pinpoint the exact moment this happened, they knew that with such a solid foundation the relationship would last. A year later they were married.

“Most marriages work on being very good friends,” David says. “We were a team,” Danielle adds.

The couple, who were right not to worry about the impact of a day off at the snow, have carved impressive careers, supporting each other on their chosen paths. Both general practitioners, Danielle is also a public-health specialist, working for a decade in Indigenous health after David was posted to Darwin with his job for the Royal Australian Air Force. This saw him serve in medical evacuation teams in Cyprus and Lebanon, with the UN in Timor-Leste, and in Bali after the 2005 bombings, and receive the 2008 Distinguished Young Alumni Award at Monash.

The couple then moved to the Torres Strait for Danielle’s work, only returning to Melbourne in recent years, along with their three young children. David, who re-trained in psychiatry, is now lead psychiatrist for emergency assessment at the Austin Hospital, while Danielle works with the Australian Red Cross Blood Service. Both recently returned to Monash when David delivered a graduation speech.

Theirs is a dynamic attitude encouraged by the approach of their intrepid, internationally focused alma mater, David says. “That’s the thing about Monash – you get your education and spread your wings and make your contribution, and it’s well beyond the campuses of the University – and that’s our careers and married life.”

Leonie and Peter Szabo

In a fateful decision 50 years ago, Leonie Szabo decided at the last minute to reject an offer from the University of Melbourne and study law at Monash University instead. It was a decision based on friendship – “everyone I knew was going to Monash”, she says – and one that would determine the longest and most significant relationship of her life.

On her very first day of orientation week, Leonie would meet her future husband, Peter, pointed out by one of her friends as living near her house and probably able to give her a lift home.

She approached him, he accepted, and the rest is history. Peter, Leonie says, was very nice from the start. “And he had a car,” she says. “He even had a new car.”

Peter graduated a year after they met, in 1969, but Leonie says in those days, when you “went to uni and stayed there all day”, there was plenty of time to get know each other. Before her third year began the couple had married, and Leonie, one of only a handful of women studying law, graduated in 1972.

While she felt no prejudice against her at university (other than there being only one female toilet), finding articles placements was tough, as firms were reluctant to hire a married woman no matter how good her degree. But Leonie persisted, completing her articles, before returning to Monash as a senior tutor. Over this time she saw significant social change, and by the time she left Monash to return to full-time legal practice, the female-to-male ratio of law students was about 50:50.

Meanwhile, Peter had become an actuary and, about a decade ago, after a successful career, he launched Homesafe Solutions – a joint venture with the Bendigo Bank that enables older people to sell a share of the future sale proceeds of their home, repaid when the property is sold.

The couple’s two daughters, Vanessa Zimmerman and Dr Rebecca Szabo, are also Monash alumni. The former is a lawyer specialising in human rights, the latter an obstetrician. Their choice of university, Peter expects, was influenced somewhat by their parents. “Leonie and I had a great time at Monash,” he says.

Leonie wonders whether one day her grandchildren may also follow their footsteps to Monash. “It’s well on the way to becoming a family tradition,” she says.

Dr Mohamed Hassan Ariff and Dr Rohana Jamil

One of the biggest culture shocks Mohamed Hassan Ariff experienced when he came to Monash University from Malaysia in 1975 to study medicine was the shopping hours.

“I was used to going out at 10 or 11 o’clock at night for food, but in Clayton after 5 o’clock everything was closed,” he says. “I couldn’t get anything. It was a shock.”

But helping to negotiate the cultural differences were the people he met through organised get-togethers for Malaysian students.

One of them was Rohana Jamil, a Malaysian-born student who had come to Melbourne a year earlier for her final year of secondary school at McKinnon Secondary College, before enrolling in medicine at Monash.

The two became friends, but it wasn’t until they both emigrated back to Malaysia in 1980 that they became a couple.

“I think it was [because] we had a lot in common being in Australia together in that formative part of your life,” he says. “And coming back we had difficulty adjusting to the Malaysian way of life, and we could understand each other.”

It also helped that, on their return, they were by chance posted to the same surgical unit in the same Kuala Lumpur hospital. Two years later they were married and today have four adult children, who are all working or studying in the medical field.

Mohamed is now a senior anaesthesiologist at the National Heart Institute, Malaysia’s biggest heart hospital, and Rohana runs a general practice.

Still, they’ve found time to return to Australia, for work at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in 1990, but also to show their children where they met. They hope to visit Monash University’s Clayton campus again in 2020 for the 40-year reunion of their 1980 graduating class. “I have very fond memories,” Mohamed says.

Professor Ingrid Scheffer and Dr Katherine Wallace

There are certain bonding experiences that come with a medical degree. For Professor Ingrid Scheffer and Dr Katherine Wallace, it was all-night study sessions in the anatomy museum surrounded by body parts; and, when, as first-years in a hospital neonatal unit, they watched a baby scream its lungs out as its wrist was ‘stabbed’ for a sample of arterial blood.

“Now I’m a paediatrician, so I know that the baby was not too sick, but the poor doctor was trying to stab its artery and all of us fainted except Kathy,” Ingrid says. “It’s events like that that make friendships, because you go through so much trauma together.”

Katherine, Ingrid says, is simply the best person she’s ever met; the person you want to be. “She’s the epitome of a good human being,” she says. “She’s kind, she’s thoughtful, she’s generous and she’s very bright.”

And there’s much Katherine admires about Ingrid, too. A trailblazing paediatric neurologist who identified the first gene for epilepsy and is defining the genetic basis of this complex group of disorders, Ingrid has achieved so much for others through her determined pursuit of excellence and wonderful communication skills. “And on a personal level, she’s a vivacious and loyal friend,” Katherine says. “She is just totally trustworthy and has great integrity and warmth.”

The two connected immediately when they met in 1978 at a university orientation party. Despite coming from quite different cultural backgrounds, the two had a lot in common.

“We just clicked as two people and became friends from that first moment on,” Katherine says.

As years went by, their friendship only grew. This, Katherine says, is because they share the same sense of humour and a passion for medicine that has seen them encourage each other in their chosen fields – Katherine is a GP and teaches at Monash – while supporting each other in their lives beyond work.

Plus, they’ve shared some significant life events. “I remember visiting Kathy to see her newborn (second) baby, Hannah, in her arms, and showing her my ultrasound of Edward, my first child, in utero,” Ingrid says.

Those two babies would grow up together and follow in their mothers’ footsteps, studying medicine at Monash. They’re now both junior doctors: Edward at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Hannah at the Austin Hospital.

“It was very exciting to see them going into medicine and then getting as much enjoyment out of it as we did, because Ingrid and I both absolutely loved medicine from the very beginning,” Katherine says. “And it’s been lovely that they’ve had a similar experience together, with their group of friends supporting each other as they went through.”

Max Ji, Jun Lee and Rio Yoon

Never in their wildest dreams did Max Ji, Jun Lee and Rio Yoon imagine that some 15 years after meeting at Monash University they would be running a business turning over $25 million a year serving Korean fried chicken and beer – no matter how delicious it is.

The international IT students had other things in mind when they met in the early 2000s. Max was busy studying computer programming, and Jun business systems. But Rio, although a computer science student, had always wanted to be a chef. And, Jun says, Rio was good; “the one who made dinner for us every day during school”.

After graduation, Jun went to work in IT, rising to the ranks of international management at Samsung’s headquarters; Max succeeded in software sales management; and Rio defied his parents and got a job as a cook. But they never forgot their promise made during regular Friday-night university bonding sessions over a few beers that, after 10 years gaining experience in the world, they would start a business together.

Max was the first to throw in his corporate job, joining Rio in the small Korean restaurant he had opened in suburban Melbourne, closely followed by another longtime friend and chef, Ayden Jung. Together they refined the vision, and opened their first Korean ‘chicken and beer’ outlet in the CBD, Gami.

Translating as ‘beautiful taste’, and built on the Korean tradition of chicken and beer eateries “on every corner” where friends get together to catch up and relax, Gami grew in reputation and, within a few years, three more stores opened.

Then, in what some called a “crazy” move, Jun quit his high-flying job “just to sell chicken with a few mates”, joining the trio in 2006. Instrumental in overseeing its growth through franchising, the move turned out to be a masterstroke, with Gami expanding to 16 stores around Australia – and a total of 21 due to open by the end of 2018.

The three say their recipe for success is an open and honest management style built on support for each other and trust that was incubated as students at Monash.

“We fight a lot – don’t get me wrong. But after a fight we always go for a beer,” Jun says. “Sometimes a whisky,” Max says.