A renaissance for the old folks at home. In the future, our elderly friends and neighbours could be seen as a precious resource rather than a problem to be managed.

“A burgeoning elderly population is actually an asset,” says software engineer Professor John Grundy. By 2050, 9.1 per cent of Australia’s residents are expected to be 80 years and older (compared to 3.9 per cent today). Professor Grundy foresees people living at home for longer, working for longer, and perhaps also providing care and guidance for their grandchildren, or young people in their neighbourhood.

Australia could already benefit much more from the experience and skills elderly people possess, he says. “There’s actually an opportunity to better enable our ageing population to have a more connected and fruitful life by careful and appropriate use of technology.”

"We need realistic solutions for everybody – not just the elite, not just the young.”

Technology “is not serving older people anywhere near as well as it could do”, Professor Grundy says. He gives the example of a future “smart home” where an older person living alone could be monitored by a range of sensors that enable them to feel “looked after, safe, secure” and also “in control of their environment”.

This might allow a person who is “lying unconscious on the floor” to receive timely emergency assistance, for instance. The technology that allows a refrigerator to remind its owner to have their midday meal, or a medicine container to indicate which pills to take, already exists, Professor Grundy says.

Read: Smart homes: innovation, evaluation and real-life experience

But before the software can be rolled out, some important hurdles need to be cleared, he says. “We don’t often ask the elderly people what they want, and everyone is different.” A software developer might think a device that tells him whether Nana has taken her medicine is a great idea, but Nana may not agree. “Some people don’t want to be monitored. Some people want a different kind of interaction or support.”

Installing and servicing tailored software across the population will be expensive, Professor Grundy predicts; the challenges will be particularly acute in sparsely populated areas.

“If you’re living on a farm or even in a small township, who’s going to look in on you?” he asks. “How are you going to access services, maybe help to do your washing, food delivery, technology updates – whatever technology looks like then … All of that will need a lot more support and care in terms of design and infrastructure than it does now.”

More people to live alone in the future

If present trends continue, more people will be living alone in the future, and not everyone will be able to stay in their homes, he says. Smaller family sizes will mean that it’ll be more difficult to care for elderly relatives who develop dementia, or who are no longer mobile, for example.

At present, “by far the majority” of dementia sufferers are cared for by their partner, friends or family, he says. With Alzheimer’s Australia, software engineers led by Professor Grundy at Deakin University have developed virtual reality technology to help carers understand the challenges a once-familiar domestic environment can pose for a dementia patient.

“You need to be very careful about how things are set out in the kitchen so they don’t inadvertently burn themselves, or cut themselves,” he says. “How do you set up pathways within the house so that you can move around when you’re liable to fall, bump yourself against sharp corners, or sharp objects and so on?”

The challenge of providing appropriate, sensitive care to an ageing population is huge, he says, and the rate of technological innovation needs to be stepped up. Human-centric software engineering – Professor Grundy’s particular interest – needs to be developed “by people, for people – hopefully to make their lives better”.

Solutions for all

The director of the Public Transport Research Group, Professor Graham Currie, agrees. The best technology “humans find really easy to use and solves their problems”, he says. For instance, “we need vehicles that everyone can use”, including children and older people. In the future, “the majority of the population is going to be older. So we need realistic solutions for everybody – not just the elite, not just the young.”

Australia is already highly urbanised – Professor Currie predicts that Melbourne and Sydney will be “the Tokyos and Londons of the future”.

“We’re going to have many millions of people in these cities, and it doesn’t make sense that we continue to travel in single-occupancy vehicles.”

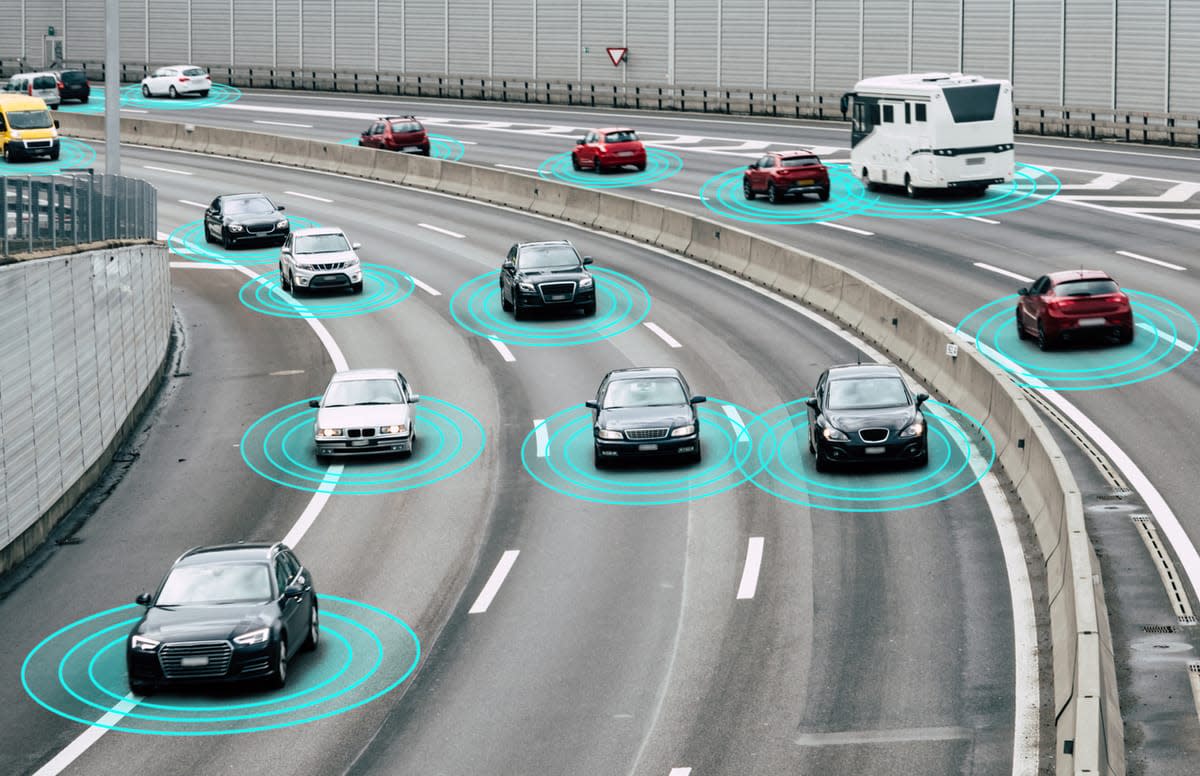

Public transport is the obvious solution – bus networks that cover the city; faster trams that are separated from traffic; driverless trains. “We need to leverage the great revolutions that are going on in public transport now, because autonomous vehicles on planet Earth today, driverless vehicles, are all trains. Forty per cent of all trains in Asia have no driver.”

Professor Currie also predicts that future travel will be more local, as a way of conserving resources and reducing congestion. “Travelling at different times rather than concentrating on travelling in the peak makes a lot of sense, and quite frankly is cheaper than providing new infrastructure.”

Thinking local with smart precincts

Professor Grundy is also thinking local, by investigating how to establish a “smart precinct” in a local government area. The project is led by Professor Le Hai Vu from the Monash Faculty of Engineering. The idea is to enable shoppers and workers who travel to the precinct to take advantage of the “increasing amounts of data-sensing intelligent technologies we have, to give them a better living experience and environment”. Professor Grundy envisages the information could be accessed via a mobile phone app.

He imagines planning a future trip to the precinct to shop and visit a cafe. Information that he’s able to access via his app could help him decide “which mode of public transport should I take, or should I take my car? What’s the parking look like down there? When are the buses going past my house, how frequently? Can I maybe connect bus and train? Is my favourite cafe going to be free at the time I’d like to go to it?”

After developing a smart home, helping build a smart neighbourhood is a natural step, he says. “There’s a lot of interest in this around the world, and I think we’ve only scratched the surface … I suspect we’ll have some really interesting ideas when we ask citizens about what they need and want, that we’ll come up with solutions that we haven’t even thought of yet.”