Dementia is one of the greatest public health and healthcare challenges of this century. Nations are grappling with the rising prevalence of dementia and its vast impacts on health services, aged care, and the broader community.

Consequently, dementia is the second-leading cause of death in Australia, and the leading cause of death for Australian women.

Governments over the past decade have responded with increased investments in dementia research, leading to significant biomedical advances in diagnostics and potential therapeutics.

It’s crucial to accompany these biomedical advances with an understanding of Australians’ experiences of navigating dementia diagnosis and care.

Such insights help shape future care paradigms and identify priorities for an equitable implementation of such advances.

We conducted qualitative research as part of the Centre of Research Excellence in Enhanced Dementia Diagnosis’s (CREEDD) pre-implementation project, speaking with 37 people who have experienced the dementia diagnosis process throughout Australia.

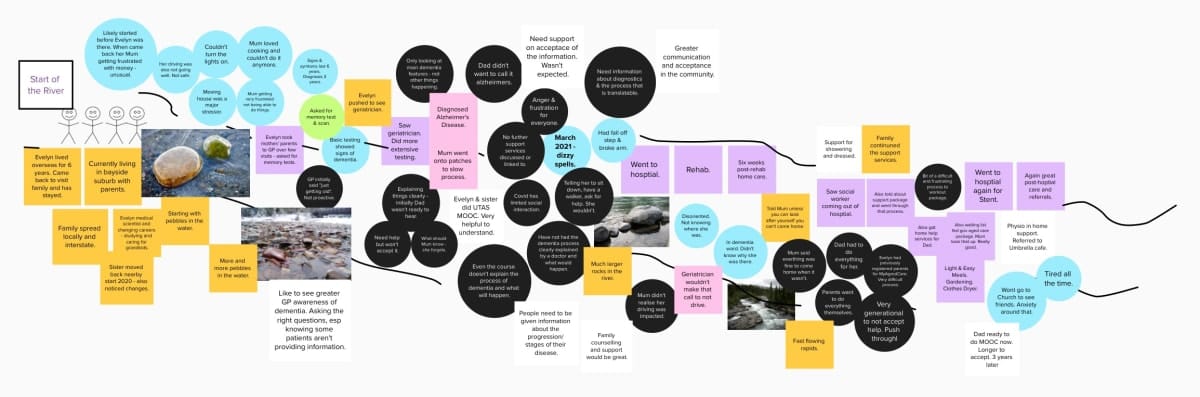

We used an arts-based method called the River of Life Storytelling, inviting interviewees to consider how they might represent their experience as though it were a river.

Interviewees included people diagnosed with dementia, people concerned about symptoms that could be dementia, people who had genetic testing identifying their dementia risk, and people who are caring or have cared for a loved one with dementia.

The interviews involved descriptions of health professionals they saw, tests conducted, experiences of attending appointments, alongside the daily activities, broader events happening, and support from family and friends along the way.

Interviews finished by asking:

“What would you like to see changed?”

This generated much discussion and passion about the urgency for governments, organisations and researchers to create a clearer, easier and more supportive pathway for Australians diagnosed with dementia.

Below we highlight the interviewees’ priorities for change in dementia diagnosis (the quotes and diagrams below use pseudonyms):

1. A consistent and clear pathway to dementia diagnosis

People spoke about feeling unsure of the diagnosis process and what it entails. In Australia, a number of specialists can diagnose dementia, including neurologists, geriatricians, psychiatrists, and occasionally general practitioners. For many people it can be confusing to understand how and when to start the diagnosis journey, and what the different specialists do.

“God, it was muddy for a long time. You are walking around with your eyes shut because you just don’t know where you’re going.” – Iris, the daughter of a person diagnosed with dementia.

2. Being told the how and why of the tests

A dementia diagnosis process can involve numerous tests – including clinical assessments, imaging (MRI scans, CT scans, PET scans), blood tests, and cognitive tests. Many participants spoke about “drawing a clock” and doing “written tests”, but often didn’t understand what the tests were for and what they were revealing to the doctor.

“The cognitive testing is very embarrassing. Most people who do it will say, ‘I hate it because it makes it very obvious that one has got a big problem with their short-term memory.’” – Felix, a person living with dementia

3. A system that supports people diagnosed and their families

Many people spoke about a complex system that was hard to navigate. The onus rests heavily with the individual diagnosed and their family to find the right pathway, navigate care systems across hospitals, aged care and social care, and solve problems. People spoke about wanting tailored information with “more than a website”, and having someone to talk to who could point them in the right direction.

“The difficulty is when you enter a really structured medical system and try to navigate that and find where you need to go. People have different pathways of getting to their diagnosis, too, so that doesn't help.” – Loretta, caregiver.

Associate professor Ayton has launched a podcast, Is This Dementia?, to help address some of the key questions raised by the research participants. You can find it on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.