Have you ever wondered what happens to the bacteria living in the food we eat?

While most of the focus is on minimising the number of harmful bacteria to improve food safety and prolong shelf-life, we often forget about other microbes that might be found in fresh produce such as fruits and vegetables.

“We’re all familiar with fermented foods like yoghurt which contain beneficial microbes, but we’ve now discovered that some fruit and vegetables can naturally contain more bacterial diversity than yoghurt,” says Dr Sam Forster, head of the Microbiota and Systems Biology Laboratory at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research.

“Our laboratory has found a remarkable number of different bacterial species living in minimally-processed foods,” he says.

“If they survive food preparation, we may consume food-derived bacteria that could ultimately colonise our gut microbiome.”

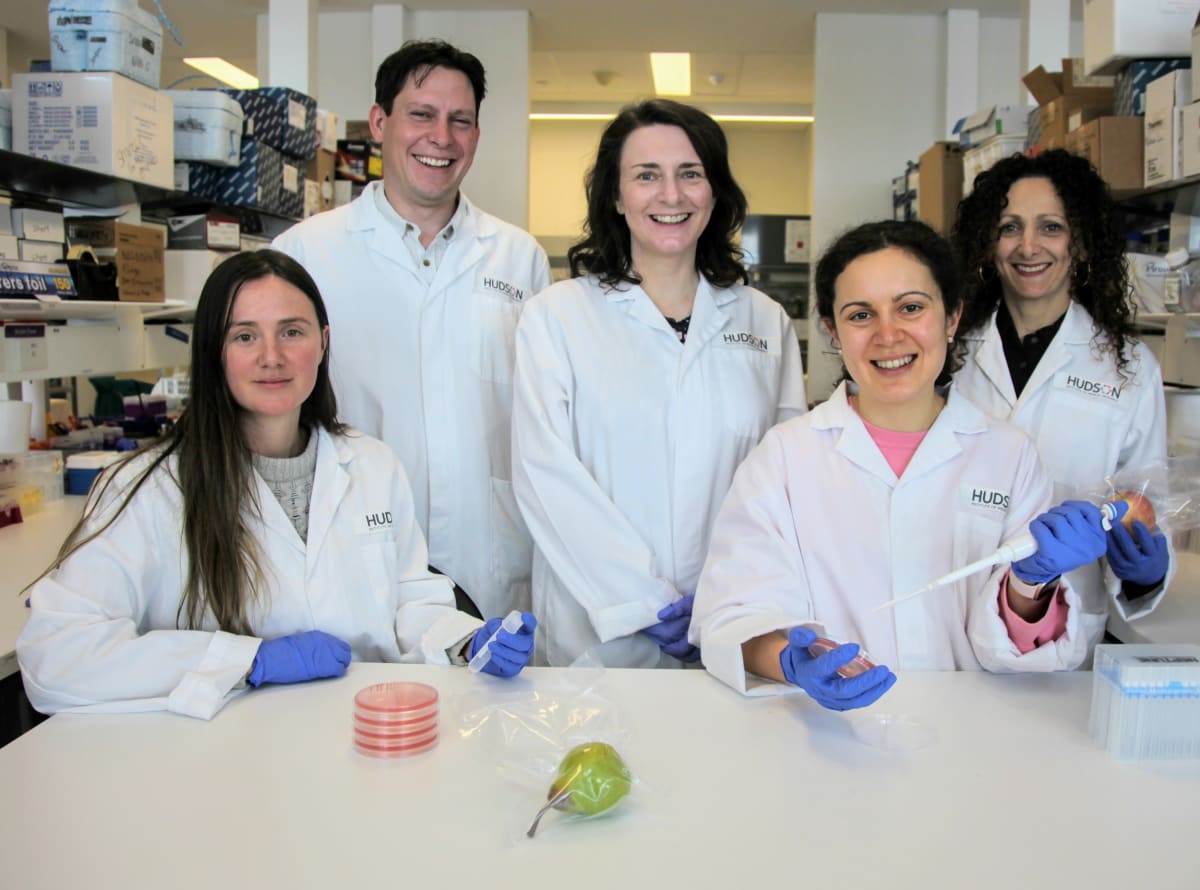

He now leads a research team of microbiologists and dietitians who were awarded an NHMRC Ideas Grant in 2020, to investigate what happens to these food-derived bacteria after they’re eaten, whether they can survive gastrointestinal transit, become established in the human colon, and potentially provide health benefits.

Major shift in gut microbiome

Researchers previously believed that the nutrient composition of food (fat, protein, dietary fibre) had the most influence on the composition of the human gut microbiota.

But that idea is now starting to change, with recent studies showing dietary changes can induce major shifts in the gut microbiome within 48 hours, and these changes are related more to the foods eaten rather than their nutritional composition.

Consuming the same food type can also have different effects on the gut microbiota of different individuals, indicating that live non-harmful (commensal) food microbes may be helping to shape the human colonic microbiome.

“A greater variety of micro-organisms living in the gut is associated with reduced chronic disease risk, so eating a wide range of minimally-processed foods containing high levels of live bacteria might be more beneficial for health than consuming sterile, ultra-processed packaged foods,” said Dr Nicole Kellow, a research dietitian at the Monash University Department of Nutrition, Dietetics and Food.

investigator), Dr Nicole Kellow (principal investigator), Emma Saltzman (PhD student), Dr Marina

Iacovou (principal investigator). Photo: Author-supplied

Surviving the gastrointestinal tract

In order to further investigate the eventual fate and function of food-derived bacteria, the team is recruiting 20 people for an eight-week clinical trial.

All food and drinks will be provided free of charge for four weeks, with meals designed by Dr Marina Iacovou (research dietitian at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research), and cooked by qualified chefs.

Participants will be required to collect regular stool samples throughout the study.

“The food provided by the research team will have a known bacterial content, so we’ll be able to detect them in stool samples if they’ve survived in the intestinal tract,” says Dr Iacovou, who specialises in formulating meals for clinical trials.

The research study is now open for recruitment. People interested in participating in this study can contact Emma Saltzman at figstudy-l@monash.edu for further information.

This project is approved by Monash Health HREC RES-21-0000-602A"