Competing use of medicines initially developed to treat type 2 diabetes has led to global shortages, sparking debate about who “deserves” to be prioritised for treatment.

These drugs, known as Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs), have in the past decade changed the approach to injectable therapy for type 2 diabetes.

GLP-1RAs are not only more effective at lowering blood glucose concentrations when compared to daily insulin injections, but some can be used only once weekly, and have a far lower risk of causing dangerously low blood glucose levels (known as hypoglycaemia).

But treatment with GLP-1RAs is also associated with weight loss (an important goal when treating most people with type 2 diabetes), and a reduction in heart attacks and strokes.

Because of these clear benefits, international and Australian guidelines now recommend that GLP-RAs should be considered the preferred injectable therapy for type 2 diabetes in most cases. But only if you can get hold of them.

Over the past year, the global supply of GLP-1RAs has been unable to keep up with demand for their prescription.

In Australia, this has resulted in shortages and ultimately exhaustion of residual stock, meaning not only that some people with type 2 diabetes have been unable to start GLP-1RAs, but also some pharmacies have been unable to fill established scripts, and many long-term users have had to change or discontinue their therapy.

Where did all the drugs go?

Although initially developed to treat type 2 diabetes, it’s become apparent that GLP-1RAs, delivered in high doses, can also induce significant weight loss in people with obesity.

For people who have struggled with recalcitrant obesity, unbudged by dieting and lifestyle change, and suffer its significant impacts on their health, GLP-1RA can achieve significant and sustained reductions in body weight unlike any medicine they’ve tried before.

In many countries, GLP-1RAs are now also able to be prescribed for the management of obesity, and are marketed in high-dose formulations under brand names that are different from those (low-dose formulations) used to treat type 2 diabetes.

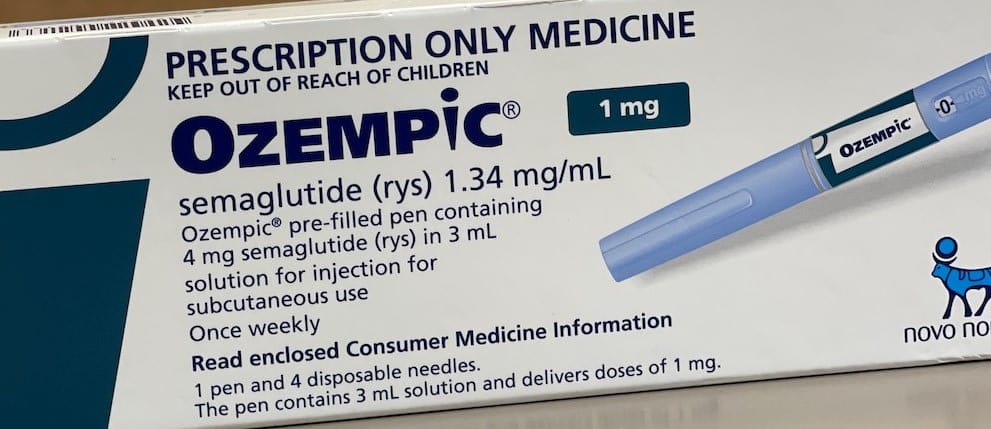

For example, the once-weekly GLP-1RA, semaglutide, is sold as Ozempic (0.5mg and 1mg) for managing type 2 diabetes, but is also sold as Wegovy (2.4mg) for managing obesity.

But such has been the demand for Wegovy, supply ran out. So physicians and patients then turned to Ozempic off-label to initiate weight loss.

In Australia, this shortage has been compounded by the fact that Wegovy stocks never arrived (due to supply), despite its approval for use in September 2022. This means that off-label treatment of obesity with semaglutide through private prescriptions has been using up the drug indicated for diabetes, Ozempic.

Understandably, this has made some (appropriately entitled) people with type 2 diabetes quite hot under the collar, filling the internet with rhetorical arguments about who really “deserves to be treated” and decrying the “cosmetic use” of “[our] drug”.

There have been calls to censor social media in Australia to prevent unsolicited promotion. Articles have also been deliberately written to highlight potential side-effects.

Recently, AMA president Professor Steve Robson weighed into the debate, suggesting reserves of Ozempic should be set aside for patients with type 2 diabetes.

However, obesity is also a disease and requires an equable response. It’s not their fault, or the platforms they use to shout out their success, that the drugs they need have been running out.

The domino effect

The global shortage of semaglutide has also had knock-on effects on the availability of alternative GLP-1RAs, including dulaglutide (sold as Trulicity) and even liraglutide (sold as Victoza) experiencing limited availability, as they get used to make up the shortfall in Ozempic, which is being used to make up the shortfall in Wegovy.

Increased demand for another GLP-RA, exenatide, has also brought forward plans for its discontinuation this year, creating another hole in supply.

In addition, the introduction of the new GLP-1/GIP agonist, tirzepatide (sold as Mounjaro) into Australia for the treatment of type 2 diabetes has been delayed until sufficient and continuing supply can be assured, due to its heightened use elsewhere, chiefly as an alternative to Ozempic – although its pending FDA approval for the management of obesity will see it also compete with Wegovy.

But, just like toilet paper during COVID-19, it’s not just demand that empties the shelves.

Pharma has also been blamed for failing to understand the market and ramp up the supply chain needed to support it. However, the need for large vats of genetically modified cells used to make GLP-1RA peptides clearly limits the speed of any commercial adaptation.

Although prohibited in Australia, pharmaceutical advertising indirectly promoting the drug treatment of obesity has also been cited. But obesity is still a disease that also deserves appropriate treatment like any other, sometimes with medication.

There is some good news

The huge demand that has caused a global shortage of these agents will lead to a massive increase in manufacture and subsequent availability.

It’s anticipated that supplies could return to Australia in the second half of this year, when Wegovy may also become available.

Should the PBS support its subsidy for people with obesity, demand will certainly tick up again. But then at least it’s likely that sufficient supply will be ready.