Did you have strange dreams during the COVID-19 pandemic?

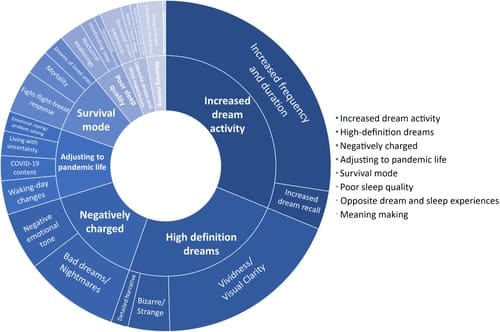

You’re not alone. Researchers have published a new study in the Journal of Sleep Research that found 45% of people in a global sleep and mental health survey had changed dream experiences during the pandemic.

The researchers, from Monash’s Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, had more than 2000 people complete the survey.

“Many reported having more dreams and nightmares than usual in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Dr Melinda Jackson, a principal investigator, senior lecturer and sleep psychologist at the Turner.

“These dreams were described in high definition – more vivid and colourful than normal, with increased visual clarity – but often had a strange or bizarre twist to them.”

These early pandemic dreams also had a more negative “valence”, or tone, with participants reporting more bad dreams and nightmares, dreaming of scary or threatening scenarios such as wars and disasters.

One participant said:

“I can't remember much now, but the dreams have been disturbing, colourful, and in some cases frightening – large-scale death, generally by war. Sometimes they wake me up.”

“There was a real ‘survival theme’ to pandemic dreams,” says Hailey Meaklim, a psychologist and PhD candidate who led the Turner’s study with Dr Jackson.

“There were lots of dreams about death, and people worrying about the safety of their family and friends. It was a scary and uncertain time for people, and these anxious feelings continued on into people’s dreams.”

“Nightmares with people I care about being sick or dying.” (Study participant)

But not all participants dreamt about pandemic-specific details.

“We did have some participants dreaming about personal protective equipment [PPE], social distancing, and fears about catching the virus, but these topics were only a small sub-theme in pandemic dreams,” says Meaklim.

“I dream about masks, making masks, and not having enough [masks].” (Study participant)

The link between poor sleep and dreams

Not everyone surveyed experienced the same level of dream changes. The researchers found people who had difficulty sleeping – with insomnia – were more likely to report dream changes than individuals who continued to sleep well throughout the pandemic.

In particular, people who developed insomnia during the pandemic had the highest proportion of dream changes (55%), compared with those who had pre-existing insomnia (that is, they already had insomnia before the pandemic, 45%), or those who were good sleepers (36%).

But do good and poor sleepers have different types of dreams?

The researchers used Linguistic Inquiry Word Count analysis to compare the language used by participants to describe their dreams. Participants with insomnia used significantly more negative words to describe their dream changes than people who were good sleepers.

Additionally, participants who developed insomnia for the first time during the pandemic used more anxious and death-related words than people who slept well.

“Overall, people with insomnia, when finally asleep, had more negative and scary dreams than people who slept well,” says Meaklim.

Why did the pandemic cause changes in dream activity?

In times of stress, it’s normal to experience an increase in dream activity.

“Increases in vivid dreams and nightmares have been observed after wars, natural disasters, and terrorist attacks like 9/11 ,” says Dr Jackson.

The threat-simulation theory of dreaming posits that during stressful events, our dreams contain threatening content and imagery to prepare us for real-life threatening situations.

An increase in stress hormones in the brain may play a key role in these changes in dream activity.

“Our brains are actually very active during rapid eye movement sleep, the stage of sleep where we experience more bizarre and vivid dreams. Our visuospatial regions of the brain become super-active, along with our emotion and memory centres. This can all be heightened in times of stress, and we get increased vivid dreams and nightmares,” says Meaklim.

Changes in pandemic sleep-wake patterns

Several other changes to sleep occurred during the pandemic that may explain the increase in dream activity.

“We saw changes to sleep-wake patterns around the world, with many people able to sleep in later due to lockdowns/work-from-home requirements. We experience more REM sleep towards the end of the night, which can be curtailed if people set an alarm to get up early for work,” says Dr Jackson.

“This natural sleep extension we saw during the pandemic may have led to increased dream recall, simply because they were sleeping in longer and having more REM sleep.”

The role of insomnia

But why did people with insomnia experience more dream changes than good sleepers?

“We have several theories about this,” says Meaklim. “One is that if people wake up directly after a dream, they’re more likely to recall it. So, if people have insomnia and are waking up more frequently throughout the night, they’re more likely to remember their dreams than someone falls straight back asleep.”

However, there may be more sleep physiology at play. The REM Instability hypothesis of insomnia suggests that people with insomnia have more unstable REM sleep, which causes them to wake up more after a period of REM sleep, and therefore recall more bad dreams. Mental health symptoms such as stress, anxiety and depression during the day may play a role, by increasing insomnia symptoms as well as bad dreams and nightmares.

“We did see that dream changes were associated with worse mental health symptoms over time, and this effect was more pronounced in individuals with insomnia” says Jackson.

The good news – dreams changes reduced over time

Thankfully, these strange dream changes didn’t last long. At three months’ follow-up, most participants noted a significant reduction in dream activity.

This continued across 12 months, with the new-onset insomnia group also having another significant reduction in dream activity from six to 12-month follow-up.

For most people, insomnia symptoms and bad dreams would have settled down after the initial stress and anxiety of the pandemic.

But if people are still struggling with sleep, the Healthy Sleep Clinic at Monash can help.

“There are good evidence-based treatments for both insomnia and nightmares, so we urge people to seek help if they’re still struggling with their sleep” says Dr Jackson.