In extreme cases, a fear of the dark is a full-blown phobia called either nychtophobia or achluophobia, which are both creepy Ancient Greek names for a condition found in children and adults that renders night, or darkness, terrifying.

Greek mythology had the goddess Nyx (“Night”) wearing a black star-studded robe; when darkness fell she emerged from a cave to ride across the sky in a chariot pulled by black horses, and was perceived as the mother of the non-daylight hours, but also of death.

“Throughout literature and culture,” says psychological scientist Dr Elise McGlashan, “the dark has been associated with things like depression, fear, sadness and ghosts.

“We often think our feelings about darkness are linked to these ideas, but our fears may actually be driven by our neurobiology.”

Dr McGlashan is a research fellow with Monash’s Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, in the Sleep and Circadian Rhythms program.

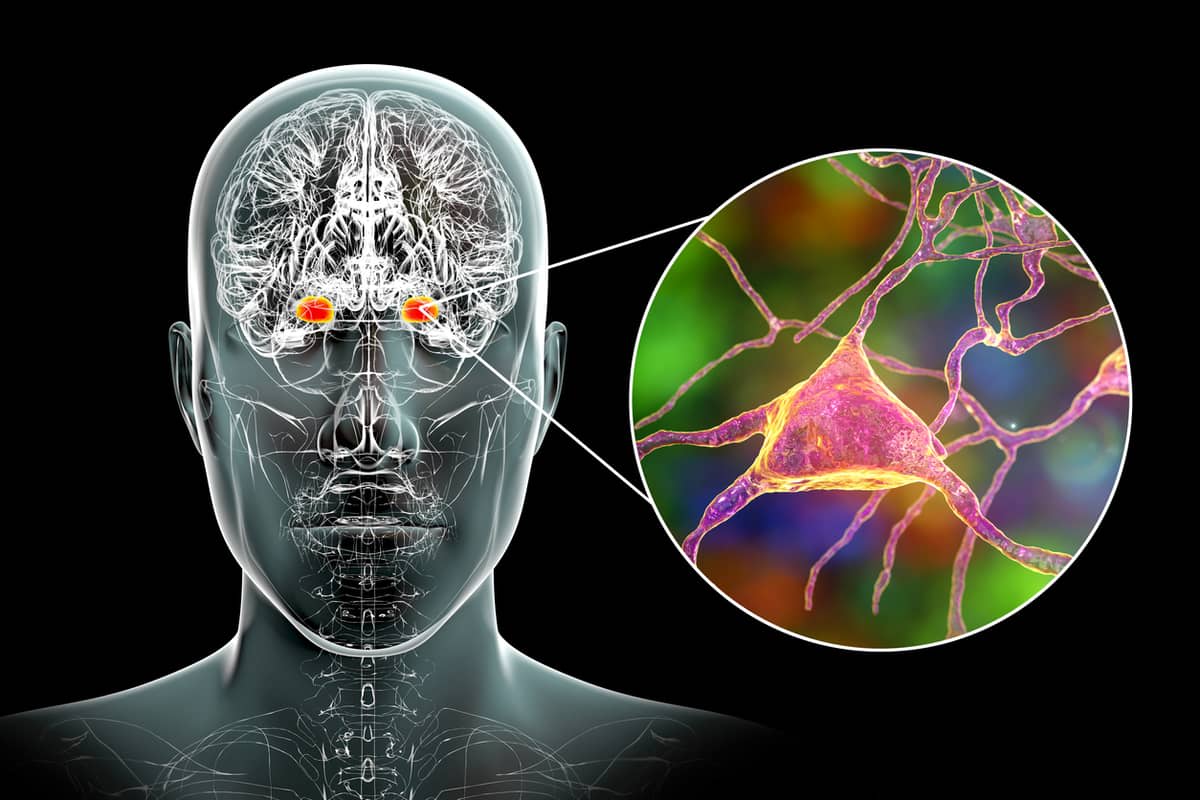

The role of the amygdala

Much of the lab’s work has focused on modern artificial light and its effect on the mind and body, but Dr McGlashan has now co-led a fascinating new study into what an absence of light – the dark – can do to a central and very curious part of the brain, the amygdala.

Among other things, the amygdala is the brain’s fear centre.

The team studies the effects of a set of cells in the eye that respond to light, but don’t contribute to our ability to see. These cells contain the photopigment melanopsin, which is most sensitive to “blue light”.

“A lot of our work has been in the context of light and circadian rhythms,” she says. “How light affects the circadian clock, and our sleep. But that’s just one of a host of what we call ‘non-visual’ effects of light on the brain.

“In addition to impacting sleep and our circadian clock, these cells in our eyes also project to other brain areas to do with alertness and mood.”

Read more: The dark side: How too much light is making us sick

In this new study, the team found that light enhances the connection between the amygdala and a part of the brain’s pre-frontal cortex, and reduces overall activity in the amygdala.

The paper states that “dysfunction in this circuitry is associated with higher anxiety”, and increased amygdala activity is associated with negative mood. The presence of light may directly lead to improved mood, and an improved ability to control our emotions.

The wellbeing benefits of light

So, light makes us feel better – more alert, more stable, and less fearful. The interesting part of this new research is that it may not be the presence of darkness per se that makes us feel fearful, as the millennia of myth, folklore and culture suggests, but rather, it’s the absence of light.

We might intuitively think that we’re afraid of the dark because we can’t see, but the team thinks there’s more going on than that.

“We’re afraid of the dark because we haven’t evolved to be active at night,” Dr McGlashan says. “We evolved to be active during the day, in the light. It isn’t a conscious effect; it’s that the presence of light changes our neurobiology in a way that makes us feel safer.”

In contrast, nocturnal animals, she says, are actually scared of light, even though it does improve their vision. “They run away and hide from it,” she says. “They feel safer in the dark, because they’ve evolved to be active during the dark. It’s just not as simple as whether or not you can see.”

The science is still young

The science on all this is still emerging. It was only about 20 years ago that the light-sensitive melanopsin-containing cells in the eye were discovered.

“The pathway by which light affects our functioning outside of vision was unknown until that revelation,” Dr McGlashan says. “There’s so much to catch up on.

“We’ve all experienced how different it feels to be in an office with huge windows, compared to one which is poorly lit,” Dr McGlashan says.

Read more: Let there be light – but make sure it’s the natural, healthy kind

“We know that light therapy in controlled high doses is an effective antidepressant. But until now we haven’t known the mechanism for how light is so effective. Our work showing light’s effects on the amygdala could be that mechanism.”

The future of this science could see light therapies used more widely to benefit more people – but also deepen our understanding of the difference between night and day, darkness and light, and what those things really mean to us as humans.