The idea of a jury – 12 impartial men and women hearing evidence, just like in a courtroom – isn’t absolutely new to medical research, but it is unusual.

The principle is to get ordinary people with no previous involvement or biases in an area of healthcare to get a crash-course in it, and report back.

According to a paper in Social Science & Medicine journal from 2014, juries “offer a useful tool for engaging citizens in health policy decision-making ... sufficiently diverse that the citizens engaged are exposed to a broad range of public experience and perspectives”.

In other words, it’s fresh eyes on an enduring problem in healthcare and public health, particularly in areas that usually struggle for ongoing funding.

“As outsiders, they saw the unique challenges of an acquired brain injury, and the fact that when you go through it, you feel so alone."

Monash University’s Professor Natasha Lannin, a neuroscientist and occupational therapist, says those “naive” to the territory can come up with the best ideas. She led a “citizens' jury” study for Monash on acquired brain injury rehabilitation.

“What we really wanted to do was put them in someone else’s shoes, and have them start to think how healthcare could tackle the issue differently.”

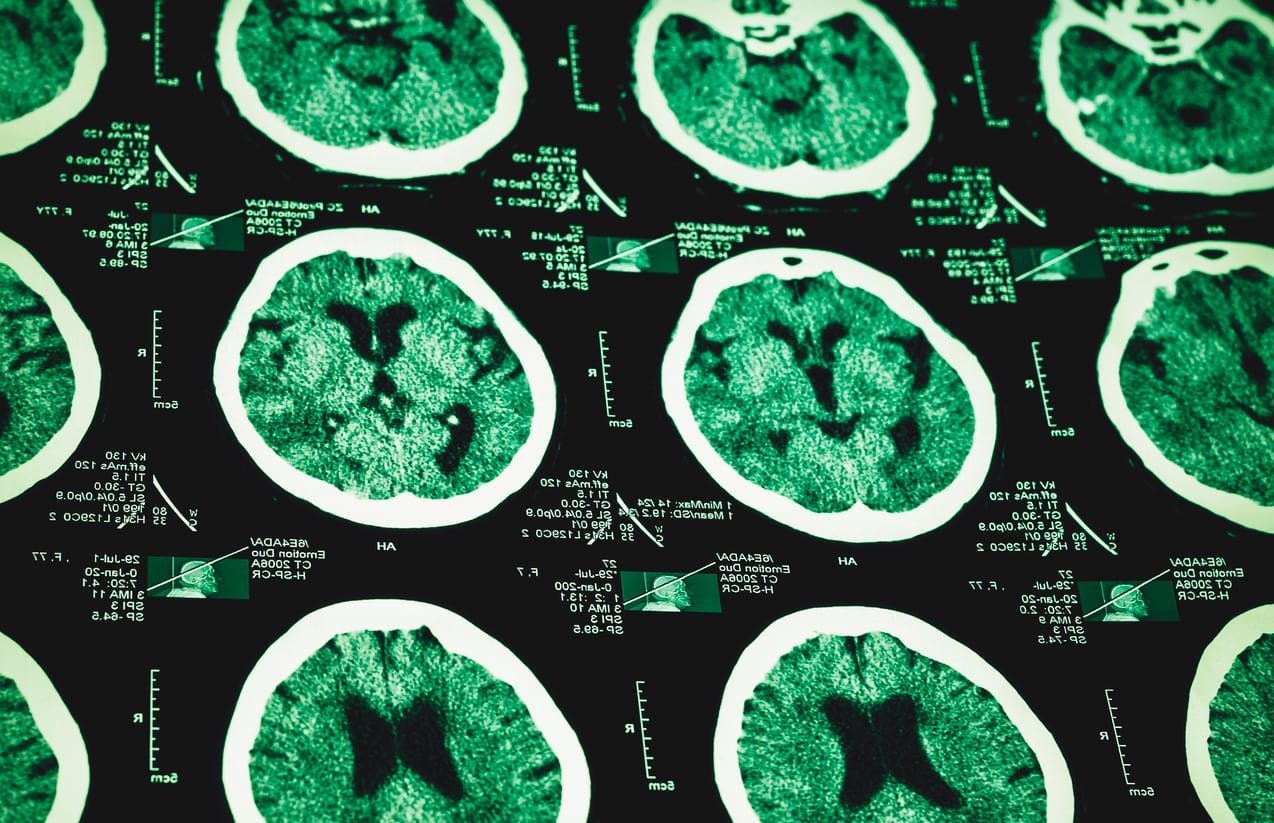

The issue in this case is acquired brain injury (ABI) rehabilitation. The paper spells out it is “expensive and (a) long-term endeavour” with “very little published information or debate” on which to build policy and delivery in Australia, especially within a context of “finite health budgets”.

Three other Monash researchers contributed to the paper: Professor of Physiotherapy Anne Holland, Associate Professor Libby Callaway, an occupational therapist, and Associate Professor Peter Bragge, of Monash’s BehaviourWorks Australia.

Jurors recruited, screened, and deployed

Twelve jurors were recruited through the electoral roll and screened for biases or personal involvement, as would happen in a legal jury. They then spent two days at a specialist brain injury unit inside a rehabilitation hospital in Caulfield, Melbourne.

The facility they saw is unique in Victoria. “It’s the first state-wide, slow-stream and long-term unit in the state,” says Professor Lannin.

“Slow-stream” in this context means the patients – with catastrophic brain injuries from accidents, falls or trauma – can stay well beyond the usual inpatient timeframes, allowing for slow gains, which is rare.

Read more: Blind spot: Are those with acquired brain injuries more vulnerable to being scammed?

Prior to this unit, many adults who suffered catastrophic brain injuries were discharged to live in nursing homes because of the level of care they needed and the lack of rehabilitation centres available.

“This facility in Caulfield has up to 42 beds each with a single room. They have ceiling hoists and all the required equipment, as well as a specialist team of nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, neuropsychologists, speech pathologists and dieticians,” she says.

The facility also offers post-discharge specialist community rehabilitation and outreach care through the ABI Community team.

Understanding the shortcomings

The jury therefore saw the best-of-the-best, with a view to them also understanding the widespread shortcomings and costs of care across the state.

They were hosted by seven specialists in ABI and rehabilitation who spoke to them and showed them data on:

- the personal and public impact of brain injuries

- funding and insurance

- personal stories of ABI and inequities faced

- how hospitals can work with ABI specialist teams

- the gap between research on brain injuries and actual clinical care

- the shortage of long-term care.

The jury found:

- flexibility and consistency are needed in healthcare to allow ABI patients to more easily access rehabilitation at times that they might need it, even many years after injury

- healthcare for ABI patients’ needs to be more family-friendly and collaborative

- patients need access to an advocate who can lobby for their needs

- public awareness of brain injuries – especially towards young males – needs to be boosted.

- brain injury inpatient rehabilitation centres need to be modernised and consider the context of a more accessible local community.

“The jury came back with strong views that there needed to be public awareness and advocacy for this group, somehow,” Professor Lannin says.

“The idea of an advocate or ombudsman is an incredibly novel solution. I hadn’t heard this raised anywhere before – someone to talk to or write to about concerns that their care may not be best-practice.

“As outsiders, they saw the unique challenges of an acquired brain injury, and the fact that when you go through it, you feel so alone. Life can essentially stop on the way to work while riding a bike or falling off a ladder.”

Data shows road trauma injuries are decreasing, while injuries from falls are becoming more common.

A fresh take on funding

Another “fresh take”, she says, was regarding funding.

“Those of us in healthcare sometimes accept the finite nature of a health budget. We accept when people say that patients have to be assessed for ongoing rehabilitation and that only certain candidates may be eligible.

“The jury came back and said, that’s not right, you should have some access to rehab, regardless how severe your brain injury is.

“But universal access to rehab regardless of severity is very challenging. Having community support from these everyday Australians helps provide a powerful motivator for policy advocacy.”