For the fifth consecutive year, more than 2000 Australians have died as a result of a drug overdose, highlighting the urgent need to prioritise public health interventions and policies that work.

This Monday, 31 August, is International Overdose Awareness Day. It's a time to remember those lost to overdose, and acknowledge the enormous loss and grief felt by families and friends. The global campaign, which began in Melbourne, also focuses on reducing the stigma of drug-related deaths, as well as the impact of overdose around the world.

Opioids – illicit drugs such as heroin, and pain relievers such as codeine, oxycodone and morphine – are the major contributor to these overdose deaths in Australia, nearly doubling in the past 10 years, from 3.8 to 6.6 deaths per 100,000.

Read more: Prescription opioids: both a blessing and a curse

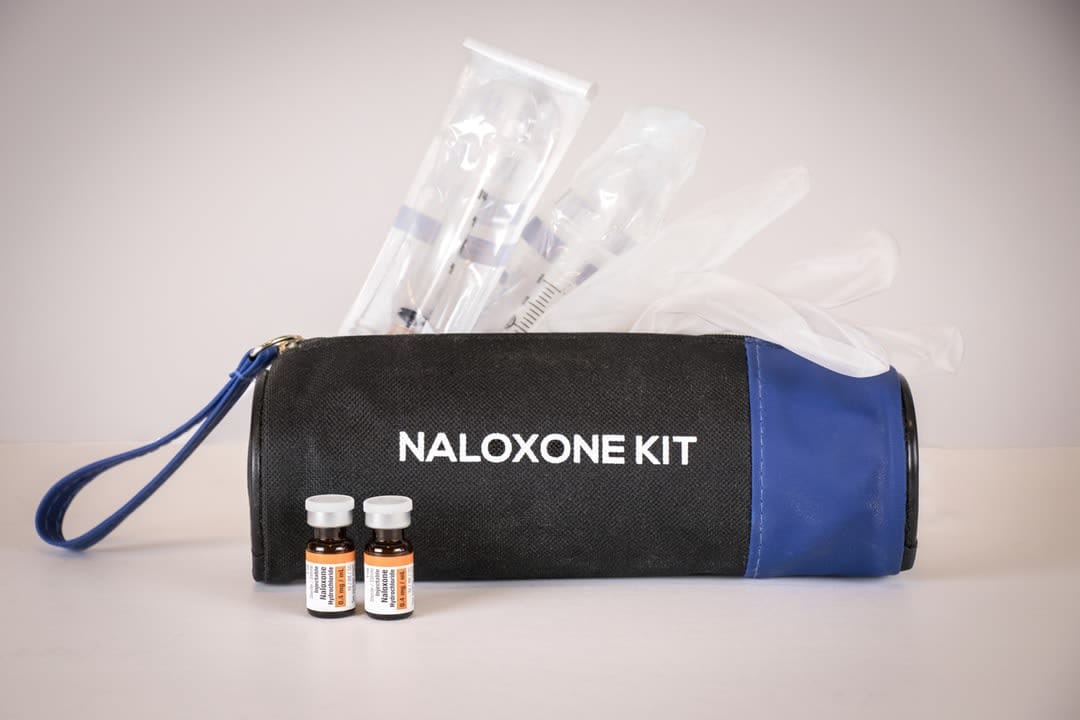

A range of important evidence-based interventions, such as naloxone, opioid agonist treatment, and supervised injecting facilities, have contributed to the reduced heroin use mortality, but this still requires substantial upscaling.

With prescription opioids now implicated in the majority of overdose deaths, Australia has started introducing a range of policies aimed at increasing the regulation of them.

These include:

- implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs

- rescheduling of the low-potency opioid codeine

- reduction in pack sizes, and limiting the indications for which opioids can be prescribed.

However, we're yet to understand the full impact of these measures in terms of reducing deaths.

While such strategies are likely to be important in reducing the number of Australians who develop long-term opioid medication dependence, the effect on those who already rely on opioids for pain management is less clear.

In the US, forced tapering or sudden discontinuation of opioid prescriptions have been followed by an increase in overdose deaths. While there are likely to be many factors involved, Australian research has found prescription opioid deaths are twice as likely to be identified as intentional when compared with heroin-related deaths. Such findings are consistent with research identifying high rates of suicidal ideation and attempts among Australians prescribed opioids for chronic non-cancer pain, many of whom report high rates of physical and mental ill health.

Read more: America's opioid epidemic is starting to hit Australia's shores

So, what do we know about the proportion of overdose deaths that are intentional, or where intent is undetermined?

A key methodological challenge here is that coding systems that provide official statistics, such as the International Classification of Diseases, require clear evidence of suicidal intent before the death can be considered to be intentional. That evidence is difficult to find in any intentional death, but for those who suicide by drug overdose, it's even more complex. Where the person was ambivalent about whether they would live or die, the task of coding becomes almost impossible.

There's growing evidence that an escape from underlying physical or emotional pain is a common driver of many overdoses. For example, in a study examining more than 4500 overdose presentations to a US emergency department, 39% of those whose most serious overdose involved an opioid or sedative reported that they wanted to die or did not care about the risks, and another 15% were unsure of their intentions.

Similarly, in a recent Australian study examining ambulance attendances related to prescription opioids, we identified that acute harms were mostly associated with pharmaceuticals taken to cope with psychological distress, physical pain or social stressors. Opioid-related ambulance attendances were also triggered by financial distress, consistent with a phenomenon in the US termed "deaths of despair", where poisoning and suicide have been linked to economic insecurity and stress.

Importantly, overdoses where the intent is unclear are unlikely to be prevented through existing overdose prevention strategies. Peer-administered naloxone and access to supervised injecting facilities will support those who do not intend self-harm, but where issues underpinning the overdose are historical trauma, mental ill health or chronic severe pain, alternative prevention strategies are also required.

However, the classification systems that inform official statistics require that deaths where intent is unclear must rightly be considered unintentional or accidental. This means that official statistics are likely to grossly underestimate the size of the problem, and key information related to these deaths is not available to inform suicide prevention strategies or relevant clinical responses.

Thus, many overdoses and deaths fall into a grey area where a clear intent to die is absent or uncertain, yet preventing death is not the focus either.

The primary driver behind some people’s substance use (regardless of whether the drug is legal, illicit or pharmaceutical in nature) is to medicate distress so that unmanageable feelings go away, irrespective of the cost. There's no clear strategy to prevent these deaths at present, as they don't fall under current responses for unintentional overdose, and they're not a target of state or national suicide prevention strategies and funding.

Understanding is the key

The challenge is how to better understand and quantify these deaths, and how to effectively respond. Developing appropriate support for family and friends, and within affected communities, to prevent further deaths needs to be a key focus for researchers and policymakers.

Critically, we must ensure that the strategies we're rapidly implementing to reduce opioid-related deaths do not inadvertently add to distress and fear among those with chronic pain who rely on pharmaceutical interventions to manage their wellbeing.

We must continue to implement and upscale overdose prevention strategies that are effective for unintentional opioid overdose-related deaths, yet we must also go beyond that. Unfortunately, there are no simple solutions for these wicked problems.

Moving forward, we must begin a more nuanced approach to determine the most effective suite of interventions and policies that address the underlying drivers of all overdose, regardless of intent, ideally with the same aspirational target of zero deaths, and the level of community and political support that we currently see for suicide.