An outbreak of plague has been occurring in Madagascar, with more than 2000 cases and 170 deaths reported since August 2017.

This island nation is one of the few remaining hotspots for plague in the world, with cases usually reported between September and April each year.

But this outbreak has been unusual, as it has affected many different areas in Madagascar, including heavily populated cities.

What is plague, and how is it treated?

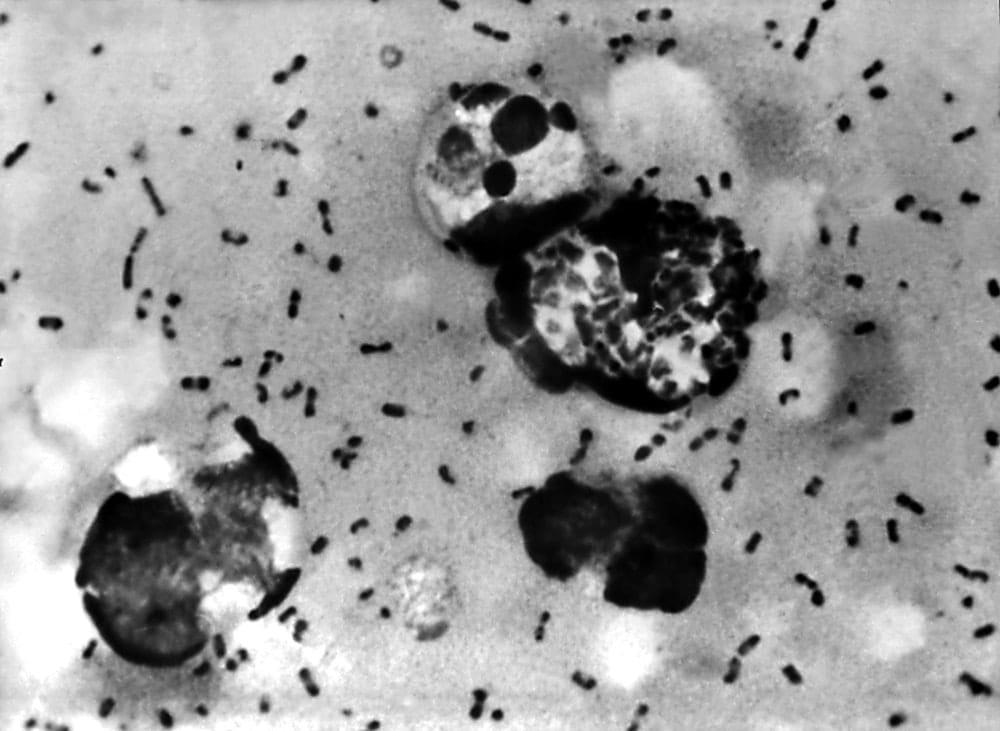

Plague is a serious disease caused by the bacteria Yersina pestis. It has a high death rate if untreated. There are several different clinical forms, including bubonic plague (affecting the lymph nodes), pneumonic plague (affecting the lungs) and septicaemic plague (involving the bloodstream).

Outside of outbreak situations, deaths from plague are usually due to delays in recognition and diagnosis, rather than a lack of treatment options. Although antibiotic resistant strains have been described, plague can generally be treated with a number of commonly available antibiotics.

Why does plague still exist?

Plague was responsible for hundreds of millions of deaths in three devastating pandemics, including the Plague of Justinian in the 6th century, the Black Death in the 14th century, and the Third Pandemic that originated in China in the 19th century.

In these pandemics, it’s generally thought plague was introduced by rats (often transported on ships) then transmitted to local rats in domestic settings. Fleas then transmit the bacterium between infected rats and humans. But there’s still some debate on the transmission pathways of plague in these pandemics. The classical cycle between an animal reservoir (rats) to humans through an insect vector (fleas) is common to many animal-associated infectious diseases, known as zoonoses.

The pattern of plague cases seems to have changed to a more complex ecology over the past 50 years. There has been a shift in cases from Asia to Africa and the re-emergence of disease in other areas such as the United States.

It’s now recognised there are many potential pathways of transmission from animals to humans in different settings. In the US, plague is thought to be transmitted from wild rodents in rural areas, such as prairie dogs and rock squirrels.

In some African countries, it’s thought cases arise where there is human encroachment into forest areas. Outbreaks have also been linked to the consumption of infected camel and goat meat in Libya, and from exposure to infected guinea pigs during preparation for cooking.

In recent years, there’s been interest in the impact of climate change on the potential for outbreaks. The prevalence of plague in animals in Kazakhstan is associated with higher temperatures in spring and rainfall in summer, as are outbreaks in the US. Tree ring studies also suggest similar climatic conditions may have triggered the Black Death and the Third Pandemic.

How can it be controlled?

Modern plague control includes finding cases and treating them, and where cases are detected, clearing homes of fleas using insecticides. Plague cases in hospitals need to be cared for safely to prevent spread to health care workers and other patients.

In affected communities, people should act to keep rats out of homes. This includes making sure food is stored and disposed of safely. Avoiding bites from fleas is also important, using insect repellents and ridding animals of fleas. Although rat control using poisons can also be used, this should only be done after fleas have been controlled, as fleas can leave dying rats and make things worse.

At a national and international level, systems to respond to outbreaks are required to make sure the public receives reliable information, to deploy logistics and resources to where they are required, and co-ordinate the various national and international organisations involved in the response.

How easily can it spread between countries?

Although the concept of quarantine arose from efforts to control plague spread, travel and trade restrictions are not often warranted given their potential economic impact. The wider fallout from outbreaks can be severe. For example, a relatively small outbreak, mostly localised to the city of Surat in India in 1994, provoked widespread panic. This resulted in a national collapse in tourism and trade that was estimated to cost up to US$2 billion.

In this current outbreak, only the Seychelles has implemented travel bans, and it’s thought the risk of transmission is low. Few confirmed cases have been reported in travellers from Madagascar during the current outbreak.

The World Health Organisation has been working with neighbouring countries to improve preparedness efforts. This includes improving surveillance at airports and sea ports, developing contingency plans and pre-positioning of antibiotics and protective equipment.

What is the future for plague?

It’s not possible to eradicate plague, as it is widespread in wildlife rodents outside the sphere of human influence. Outbreaks generally are managed reactively by “firefighting teams” deployed to clear houses of fleas, identify and treat cases and give pre-emptive treatment to contacts at risk.

A more preventative approach, such as the identification of areas at risk using climate models and animal surveys to focus flea and rat control efforts would be better. But this requires a better understanding of transmission pathways in each region where disease persists.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.

Allen Cheng is a professor in infectious diseases epidemiology at Monash University. He receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council.