The “smart camera” industry has seized on the COVID-19 pandemic as a business opportunity to promote its ability to monitor, track, and identify people at a distance.

Companies are promoting systems to identify people who have received a positive diagnosis, and to enforce quarantine and social distancing restrictions.

In Australia, the Chinese company Hikvision – an industry leader in facial recognition technology – is promoting the use of smart cameras equipped with thermal sensors to identify at a distance people who may be running a fever. The company envisions the deployment of the cameras in a range of locations, including nightclubs, schools, and aged care facilities, to help detect and prevent the spread of the virus as restrictions ease and facilities reopen. Similar systems have been used in China, and in airports internationally, to detect symptoms while minimising close-range exposure.

These developments add to the recent push to deploy facial recognition technology for uses ranging from public safety to workplace monitoring and “frictionless shopping” (when a camera identifies shoppers in order to directly debit their accounts for the goods they purchase).

In Australia, plans for the creation of a national facial recognition database (the National Driver Licence Facial Recognition Solution, or NDLFRS) continue to progress. As of writing, three states (Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania) have already uploaded their information to the system, and the remainder of the country is expected to follow in the next 18 months.

However, proposed legislation governing how this database could be used by law enforcement was sent back for an overhaul last year following a finding by Parliament’s Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security that it lacked necessary privacy safeguards.

As the government reconsiders how best to craft the legislation that will shape the deployment of a powerful surveillance tool, now is the time to foster public awareness and discussion of public priorities and concerns with respect to its development and implementation.

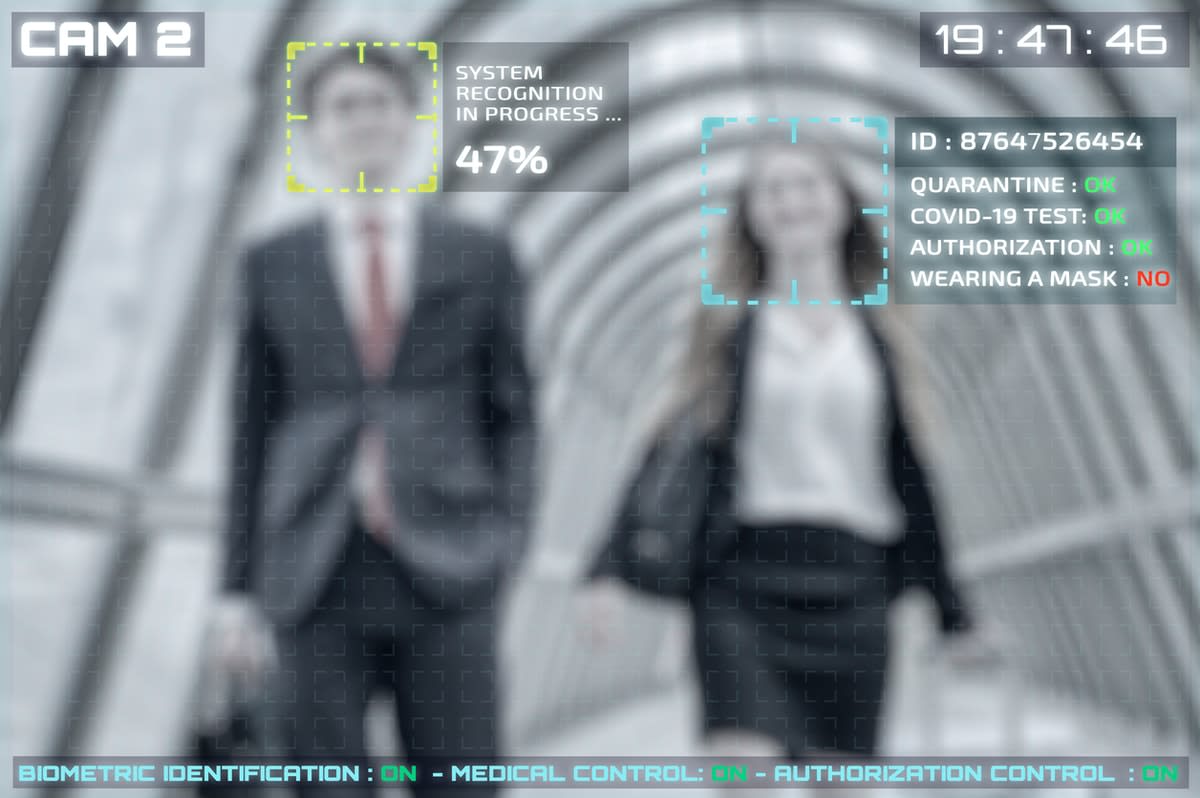

Facial recognition technology has the capability to radically transform our sense of anonymity in shared and public spaces. Even if we don’t always have an expectation of privacy when we’re out in public or in the presence of others, we know that most of the time our actions aren’t captured and stored, or linked to identifying information. People may see us stop in front of a shop window or enter a health clinic, but they’re unlikely to remember us, especially if they don’t know who we are. We know there are CCTV cameras in public places, but we don’t expect them to recognise who we are.

Facial recognition technology could dramatically revise those expectations, depending on how it’s implemented, ushering in new forms of increasingly comprehensive monitoring and surveillance.

Public concerns about privacy, security, and bias

A recent Monash survey of Australians’ attitudes towards the use of facial recognition technology revealed significant concerns about privacy, security, and bias. It also indicated a relatively high level of agreement that facial recognition could be an important tool for public safety (61 per cent) – qualified by high levels of uncertainty, and relatively low levels of knowledge about how the technology works.

Even though most of our respondents had heard of facial recognition technology (88 per cent), fewer than one in 10 (8 per cent) felt they knew a lot about it.

A significant plurality of respondents, 49 per cent, agreed with the statement that the use of the technology in public places is an invasion of privacy. Only one in five disagreed with this statement (the rest were undecided or didn’t know).

More than a third of respondents (37 per cent) agreed that the risks of using the technology outweighed the benefits (25 per cent disagreed, and the rest were undecided or didn’t know). These results suggest the need for an ongoing, informed discussion of the actual utility of the technology, and its impact on privacy rights.

Other concerns about facial recognition technology reflected research that indicates it can be biased by gender and skin colour – a fact that has disturbing implications for a technology that could have significant legal impact on people’s lives.

More than a third of respondents agreed that the technology isn’t accurate enough to be practical (36 per cent), and a similar number were concerned about racial bias (37 per cent). Almost two-thirds (64 per cent) felt that databases weren’t secure enough to protect people’s data.

In cases of commercial use, facial recognition was deemed more acceptable if it was used for managing potentially illegal behaviour than for advertising or marketing purposes. Workplace uses of facial recognition were generally the least-supported overall, likely due to the perceived infringement on worker rights and autonomy.

In many cases, the survey yielded a high percentage of “undecided” responses, further bolstering the case for more public education about the capabilities, uses, and risks of the technology.

Despite some of the media coverage of the results, we don’t see the survey as an indication that the public is unconcerned about the prospect of the widespread implementation of facial recognition technology. Rather, the findings combine a desire for safety and security that enhanced surveillance promises – often in the absence of any actual evidence – with significant concerns about the implications for privacy, security, and wellbeing.

What we still need to do

In response to the findings, we propose the following:

- The importance of increased public awareness and discussion of how facial recognition and related technology works, and how state and commercial entities plan to implement it. For example, there was strong support for the ability to opt out of facial recognition databases, whereas this is not envisioned in the plans for the NDLFRS.

- The need for policymakers and legislators to engage in a public dialogue as it crafts enabling legislation for the use of the database. This is a complex regulatory convergence environment that will require expertise from multiple stakeholders, experts, and representative bodies to create meaningful legislation that benefits the public and maintains privacy.

- Given concerns expressed by both respondents and the Australian Human Rights Commission, which has called for a moratorium on potentially harmful uses of facial recognition technology, its implementation needs to be preceded by a rigorous technical examination and public discussion of security, biases and inaccuracies. Since the use of the technology can have serious consequences for people's life circumstances, there’s a compelling case to delimit the implementation and use of facial recognition technology, as other countries and jurisdictions have done.