“[T]he tissues dry out, the muscles weaken, the skin sags. The bones. . . become brittle and porous, easily fractured . . . Deprived of its natural fluids by the general desiccation of tissues, the entire genital system dries up. The breasts become flabby and shrink, and the vagina becomes stiff and unyielding. The brittleness often causes chronic inflammation and skin cracks that become infected and make sexual intercourse impossible . . . nervousness, irritability, anxiety, apprehension, hot flushes, night sweats, joint pains, melancholia, palpitations, crying spells, weakness, dizziness, severe headache, poor concentration, loss of memory, chronic indigestion, insomnia . . . no woman can be sure of escaping the horror of this living decay.”

You could be forgiven for mistaking the above paragraph for a description of a woman in a horror movie transmogrifying into a zombie-like creature, but you’d be incorrect.

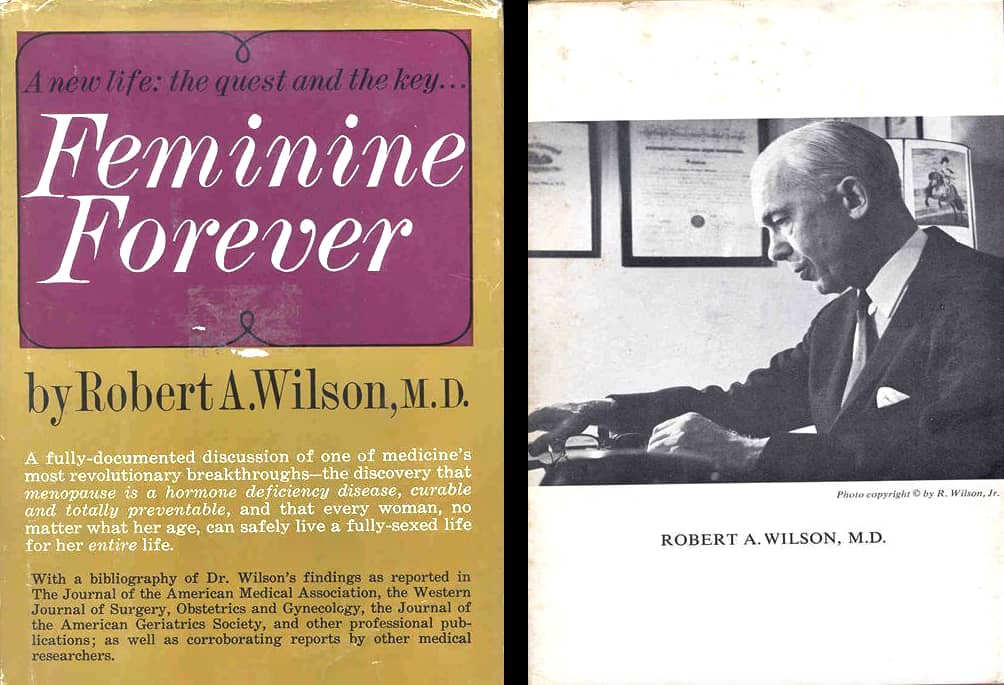

The quote is from gynaecologist Robert A. Wilson’s 1966 book, Feminine Forever, and it’s his gruesome depiction of the effects of menopause, a condition he repeatedly refers to as “castration” and as a “mutilation of the whole body”.

Throughout its 224 deeply problematic pages, Feminine Forever portrays menopause as:

“[T]he transformation, within a few years, of a formerly pleasant, energetic woman into a dull-minded but sharp-tongued caricature of her former self.”

Wilson makes the disturbing claim that, after menopause, women are “no longer women”. It’s tempting to dismiss this pathologisation of a natural process of ageing as backward thinking from a different time, but the book enjoys a 4.3-star rating on Amazon USA and five stars on Amazon Australia, and some of the accompanying reviews suggest that little has changed.

If Wilson’s terrifying depictions are to be believed, it’s more than a little surprising that menopause hasn’t been the subject of close examination and representation in entertainment media, particularly within the horror genre.

I’m especially bewildered by the complete lack of direct engagement with menopause within the sub-genre of body horror, also referred to as biological horror.

Body horror centres bodies as the focus of anxiety, fear, and disgust. As Xavier Aldana Reyes from Manchester Metropolitan University puts it:

“[I]ts workings involve the inscription of horror onto the human body by virtue of a change, or series of them, that transforms the perceived ‘normal’ body into a negatively exceptional and/or painful version of itself.”

The body horror genre hasn’t shied from engaging with other transitional times in the female life cycle.

Puberty (especially the onset of menstruation), sexual awakening, and motherhood have all been explicitly examined in body horror films.

Menopause, however, which Dr Erin Harrington from the University of Canterbury rightfully says, “marks a period of social and sexual transition for women that is no less important”, remains uncharted territory.

The journey from perimenopause to post-menopause is rich with body horror fodder, and I think it deserves specific engagement within the genre.

Abjection and the ageing female body

French philosopher Julia Kristeva uses the term “abject” to describe that which disturbs the identity of the self; that which confronts us with our “corporeal reality” – for example, bodily excretions, physical wounds, and corpses.

Kristeva explains that it is:

“... not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection, but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules.”

Dr Harrington writes that zombies are “the abject body par excellence”, and offers zombification as a metaphorical lens through which to examine the abject menopausal body.

Harrington identifies the source of abjection to zombies as the “perpetual threat of one’s own transformation”, which means that “its threat comes from within”, and she draws a parallel to “[t]he shift from fecundity to infertility as a persistent ‘threat’ from within”.

The connections couldn’t be clearer. So why is menopause so glaringly absent from body horror?

Read more: ‘It changed who I felt I was.’ Women tell of devastation at early menopause diagnosis

Dr Harrington suggests—and I agree with her— that “the figure of the older woman is so profoundly abject that it is not deemed to be reasonable for an audience to identify with her or want to watch her”.

This isn’t to say older women don’t appear at all in horror movies. There are plenty of depictions of decrepit, youth-stealing hags and psycho-biddies within the genre, but I’ve been unable to find any direct engagement with the rich, transitional journey of menopause.

So, when I took part in a devised theatrical production at Monash University titled Body Horror, I attempted to remedy that.

Disappearing women

I’m at the very beginning of my perimenopausal journey. My body temperature changes suddenly, my menstrual cycle is shifting and becoming less predictable, my skin is losing its elasticity, and I experience frequent bouts of irritability that – more often than I’d like to admit – shift into uncontrollable fits of rage.

My middle-aged female friends and I discuss our changing bodies and temperaments with good humour and just a hint of nervousness.

It’s strange and unsettling to look in the mirror and witness the slow but relentless transformation. It feels almost like the onset of a second puberty.

Depending on the day, the “threat from within” can seem all too real, and I find myself pulling at the skin on my neck in a performative attempt to coerce it back to its younger state. I don’t like that I do that, but I’m not immune to cultural programming, and, in my mid-40s, I’ve noticed myself becoming less “visible”, a broadly – if only anecdotally – documented phenomenon experienced by many middle-aged women known as “invisible woman syndrome”.

The cultural rejection of the (abject) ageing female body renders middle-aged and older women almost invisible, which many women find not only personally destabilising, but socially and professionally disruptive.

For time immemorial, women have been subjected to what Dr Harrington calls “the phallocentric order that centralises reproduction as the use-value of the female subject”, so, despite its unfairness, the phenomenon isn’t surprising.

Invisibility as a superpower

When the devising process first started for the Body Horror production, I found myself wondering how I’d be able to incorporate myself, a middle-aged woman, into a genre that generally excludes women my age.

I joked: “You want body horror? Try waking up at night drenched in sweat, or feeling like murdering someone just for leaving a cup in the sink!”

I was being flippant, but it seemed as good a starting point as any. What could I say about my experience in a changing female body?

The thing that makes this time of transition so interesting and worthy of enquiry for me is not just the observable physical transformation (although it’s a compelling aspect to a horror narrative), but also the powerful, spiritual metamorphosis that takes place alongside it.

There’s a feeling of sharing my body with a second soul of sorts – a prickly, rage-filled, formidable spirit – who’s slowly taking control. She’s at once terrifying and alluring, and her transgressive and destructive potential is only enhanced by the invisibility of my corporeal form.

My monologue is performed in a bath filled with red-stained water, a symbol of my menstrual cycle (and my fertility) leaching out of my body. I narrate a violent dream in which I eviscerate and neuter a man (a symbol of the patriarchy.)

The last line is a titillating suggestion (for other middle-aged women) and a warning (for the patriarchy and its upholders) that my invisibility isn’t a weakness, it’s a supernatural power; a cloak under which I can wreak all sorts of havoc upon oppressive systems that I want to destroy.

Although the article is written in gender binary terms, the author acknowledges that people who do not identify as women also experience menopause.