Last week, menstrual pad brand Libra launched its Blood Normal commercial in Australia, running it during prime-time TV shows including The Bachelor, The Project and Gogglebox. Australia is a little late to the party – Blood Normal first ran in the UK and Europe in October 2017, and won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2018 for its de-stigmatised depiction of menstruation.

Breaking ground in menstrual product advertising terms, the ad has received most attention for showing menstrual blood as red and on the inside of a woman’s thigh, rather than as the bizarre blue liquid we’ve seen for decades being squirted onto a pad by someone in a lab coat.

Busting period stigmas

The ad bombards us with a rapid-fire array of stigma-busting micro-dramas featuring fashionable young people (some of whom are well-known European cultural influencers). A hip boyfriend (Swedish fashion blogger Julian Hernandez) buys pads in the local supermarket; a young woman (French activist Victoire Dauxerre) stands up and asks “Does anyone have a pad?” across a dinner table of hipsters; a university student walks into a public toilet carrying a wrapped pad openly in her hand; a woman’s fingers type: “I am having a very heavy period and will be working from home today.”

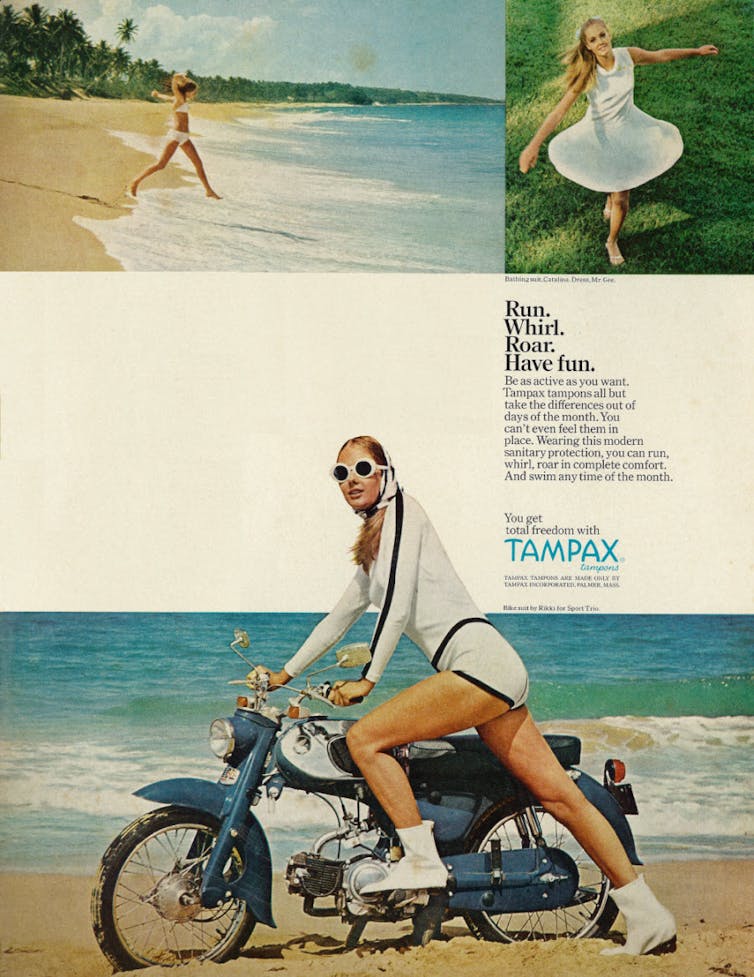

Unpacking the ad reveals a combination of the old and the new in menstruation ad-land. There's the tired old trope of the menstruating woman engaging in boisterous and fun physical activity, echoing the freedom message of women dressed in (improbable) white, riding horses and motorbikes in ads from the 1960s on.

In Blood Normal, though, the notion that a menstruating woman can do anything is taken into more intimate territory, with a scene of a couple having (gentle) period sex. A woman shown at the swimming pool looks serene and thoughtful, more as if she's taking time out for self-care than trying to prove menstruation doesn’t make any difference in her life, and that she's as non-cyclical as a man.

The modern-day stance that menstruation should be suppressed emerged from the second-wave feminist need to assert women’s equal rights within a still-masculinised world.

Where Blood Normal really breaks ground is by presenting all the moods and moments of the menstrual experience, including the pain and the turning inward. It also does a brilliant job of showing the sweetness of getting and giving support within a sisterhood and brotherhood, in an idealised setting in which everyone is menstrually-aware.

This vision may be nearer than we might think: the characters in Blood Normal are in their teens and 20s, and recent reports indicate this generation is rapidly shifting in terms of menstrual norms. Young women are reporting much higher interest in menstrual cycle awareness and it is now one of the “biggest wellness trends”.

In Australia, talkback radio reflected this shift, picking up on suggestions of menstrual leave. Celebrity Yumi Stynes' book for first-time menstruators, Welcome to Your Period, was published this month.

Menstruation is big business

Despite this ad being touted by its makers as a public service, we cannot forget the corporate profit-driven self-interest involved in menstrual product ad construction. Recent valuations of the “global feminine hygiene product” market (of which about 50 per cent is menstrual pads), vary from US$20.6 billion (A$30.5 billion) to US$37.5 billion (A$55.5 billion), with projections of US$52 billion (A$77 billion) by 2023.

High profit margins along with environmental devastation are contained within those figures. Disposable products use up resources, clog landfill sites, and pollute oceans. In the past, manufacturers have been less than honest about product safety, such as in the infamous Rely tampon Toxic Shock Syndrome scandal.

Menstrual product advertising has been shown to increase self-objectification and has cynically exploited and added to anxiety surrounding leaks and smells.

There’s a massive gulf between the sweet and loving world of the Libra ad and the uncomfortable reality of the disposable menstrual product industry.

More work to do

So, why now? Why has it taken the disposable menstrual product industry almost a hundred years to talk about menstruation as normal and in terms that actually match lived experience, rather than as an unspeakable problem that their products will absorb and conceal, allowing the menstruator to “pass” as a non-menstruator.

The answer partly lies in the process of cultural change – things take time, and menstrual stigma was a big chunk of patriarchal power relations for feminism to tackle. It also lies in the influence of the new “femtech” – new cycle tracking apps, and reusable pads, period underwear, and menstrual cups made using new technologies. These innovations are reshaping menstrual experience in ways that disrupt self-objectification based on stigma, while replacing it with new forms of control through data collection.

Blood Normal is a great ad campaign, and yes, menstrual stigma is being dismantled. But we’re not there yet. When all women have access to reusable, sustainable menstrual products; when menstrual self-care becomes a cultural norm in homes, schools and workplaces; when women feel free not only to jump around when bleeding, but to live with the cycle rather than against or despite it … then we’ll be there.

Lara Owen is a founding member of the Menstruation Research Network (UK) funded by The Wellcome Trust 2019-2020.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.