The first time Kevin Bell saw an Australian Aboriginal was at the Royal Melbourne Show, where black men sparred with any white man who stepped up to “take a glove” in Jimmy Sharman’s boxing tent.

As a boy, he found this racially-based spectacle to be “very confronting”.

“I thought that things have got to be better than that.”

The former Supreme Court judge now has a historic opportunity to improve black and white relations in Victoria. He’s one of five appointees (the only non-Aboriginal) to the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission, a royal commission tasked with hearing evidence of past and present injustices against Victoria’s First Peoples.

“Yoo-rrook” is a Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba (an Aboriginal people in northwestern Victoria) word meaning “truth”. It’s the first truth commission to be established in any Australian state or territory, and forms part of Victoria’s treaty process with its Indigenous peoples.

Read more: What have we learnt 30 years on from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody?

The commissioners will investigate the impact of European settlement on Victoria’s Aboriginal communities, with the aim of balancing the historical record by allowing them to tell and record their side of the story.

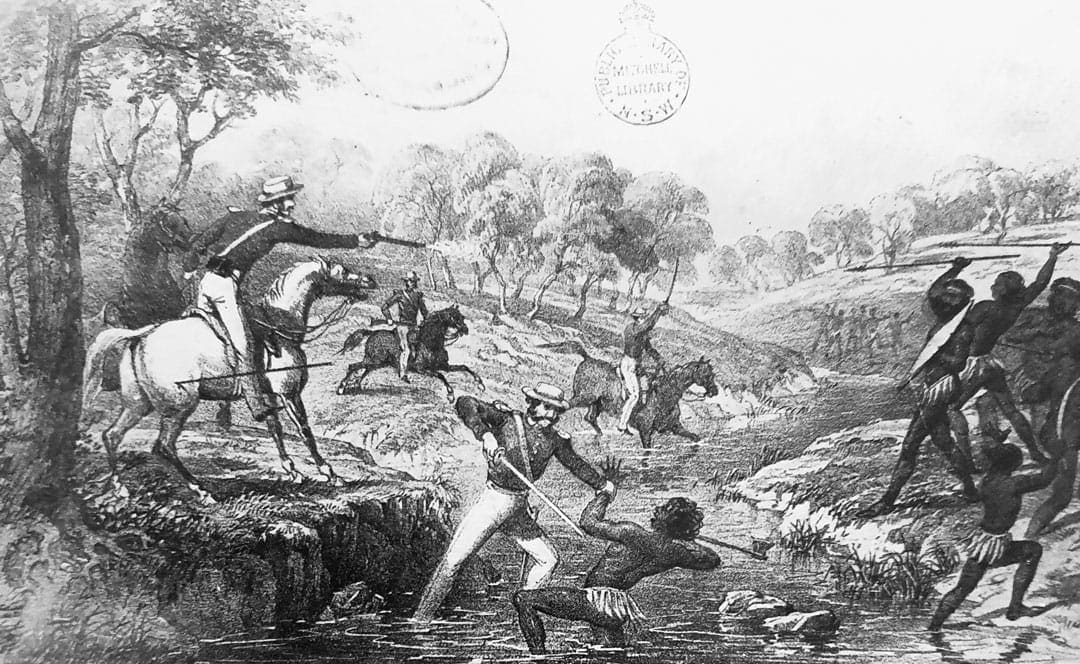

“Part of the commission’s function is to enable the truth to be told, to present a mechanism through which the Indigenous narrative can be explained and recorded in a culturally safe manner,” Professor Bell says. Hidden stories of massacres and dispossession will be told alongside “the narrative of resilience and recovery, which has manifested in the very existence of the commission”.

The other commissioners are Wergaia/Wamba Wamba elder Professor Eleanor Bourke, an Indigenous studies academic and welfare worker, who will serve as chairwoman; Yorta Yorta/Dja Dja Wurrung elder Dr Wayne Atkinson, a traditional owner and human rights advocate; Wurundjeri and Ngurai illum Wurrung woman Sue-Anne Hunter, a trauma and healing practices specialist; and Palawa (Tasmanian Aboriginal) woman Professor Maggie Walter, a sociologist.

Curriculum change on the agenda

The commission aims to gather evidence about the state’s past treatment of Indigenous people that has yet to find its way into school curricula – one of its tasks is to make suggestions for how the curriculum might change.

Victoria’s post-colonial history includes conflicts such as the Eumeralla Wars in the Western District that were reported at the time but have since largely faded from public memory, or the smallpox epidemics that decimated Victoria’s Indigenous populations before Batman made his treaty with the Wurundjeri in 1835. (The treaty wasn’t recognised by the colonial powers at that time.)

Many atrocities were deliberately kept secret; some were revealed by survivors decades afterwards; and there are those that have been recorded and will be told.

Read more: Australia’s history is complex and confronting, and needs to be known, and owned, now

How will the commission deal with past events that have largely stayed in the shadows?

“By evidence, by formal means,” Professor Bell says. “There is an historical record. This area now is not new territory, because there are scholars – for example, at the University of Newcastle – working on the whole issue of massacres.

“We will draw on their work. We will take evidence from individuals who will tell us their stories. Family history is legally admissible as evidence in this kind of context. It has a value which needs to be recognised, and will be.

“It’s not necessarily determinative, but what is remembered by elders and people with the cultural authority to speak on behalf of Indigenous peoples is part of their own reality. It doesn’t just shine light on what happened, but shines light on how they’ve responded to what’s happened.”

Drawing on the Canadian experience

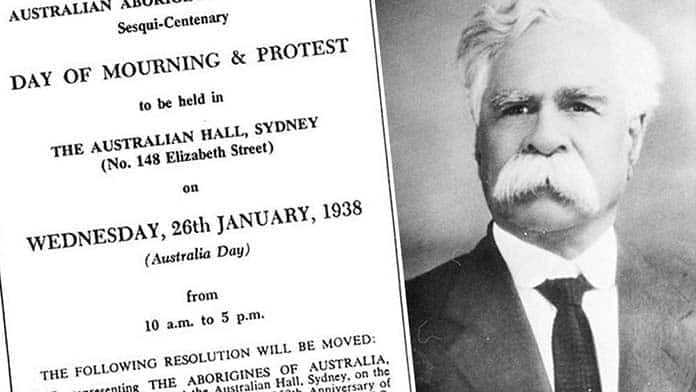

Truth commissions have previously been established in other countries, including Colombia, South Africa and Canada.

Canada’s experience is the most relevant to Australia, Professor Bell says, because it was also a Commonwealth settler nation, with settlement taking place on lands previously enjoyed by First Nations people. Its inquiry into the residential schools system produced alarming findings of cultural genocide and assimilationist practices.

How will the Yoo-rrook commission’s work, which is expected to take three years, be connected to Victoria’s treaty?

Truth-telling “is the sine qua non, the essential precondition, for any kind of partnership represented by a treaty”, Professor Bell says.

“There must be some interaction at the deep, moral level between the various elements of the Victorian community, so that we can truly understand each other,” he says. “Speaking personally, for my children and grandchildren, and for those coming even after them, I believe this provides for a richer, more inclusive sense of community than the one we have now, where so much of what has happened doesn’t rise to the surface.”

Read more: The ‘frontier wars’: Undoing the myth of the peaceful settlement of Australia

As a young lawyer, Professor Bell worked on two large successful native title cases in the Kimberley in Western Australia, as well as a case in the Northern Territory.

But native title has been more difficult to establish in Victoria, one of the most densely populated regions in Australia. The Yorta Yorta people, for instance, experienced a setback of their native title claim in 2002, which led to the Victorian government introducing land justice legislation with the aim of responding to the historic wrong of their dispossession.

About 30,000 Indigenous people live in Victoria today, many in urban areas.

A settlement to shape the future

Professor Bell describes the treaty “as a mechanism whereby Aboriginal peoples in Victoria can reach a settlement about the shape of the future political order of this state, as it affects them”. He adds that these structures “are founded on acceptance of the Commonwealth Constitution and the Federation”.

For instance, the commission will consider how, within the state’s existing governing structures, “Indigenous people can achieve substantive self-determination and go forward with their own development, politically, socially, economically, and culturally”, he says.

“It will deal with reparations, memorialisation, new treaty-based mechanisms through which Indigenous people can exercise real power and achieve autonomy in their own interests within the Victorian body politic and political system. This is the fundamental message of the Uluru Statement from the Heart: Voice, treaty, truth.”

Read more: AFL allies: How Indigenous footballers joined forces to fight racism

One question will be how “the Indigenous perspective can be expressed to Parliament and to government”, he says. Another “concerns autonomy and self-government for Indigenous peoples in relation to affairs that concern them directly”. These include, for example, “education, health, some aspects of justice administration, and caring for Country”.

In Australia, treaty-making processes have also started in the Northern Territory. They began in South Australia, but paused after a change of government.

Nationally, the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart called for a truth-telling inquiry into Australia’s history and colonisation, which it called the Makarrata Commission. It also called for a First Nations voice in the Australian Constitution.

Victoria will set the precedent

What happens in Victoria “will set an important precedent for treaty-making and truth-telling commissions in other parts of the country”, Professor Bell says.

In the meantime, “there’s much to be done in the way of sharing more respectfully and equally the space that we occupy together, to bring the Indigenous spirit to the surface”’ he says.

“The naming of public places, the presence of Aboriginal ceremony in community affairs, the ways in which Aboriginal languages are preserved, recovered, taught and shared are some examples of where progress can be made.

“We can look at how other jurisdictions have brought the Indigenous spirit to the surface in a way which makes the community more complete, fuller, more respectful, more inclusive and richer,” he says. “An obvious example is Aotearoa New Zealand, where aspects of Maori culture have penetrated and risen much more to the surface.”