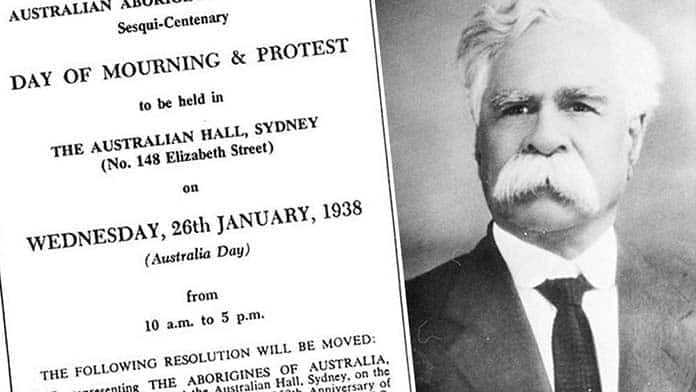

Three years ago, cardiologist and Monash PhD student Jessica O’Brien began an important heart research project looking at ways to understand a potentially fatal but preventable disease affecting mainly young Indigenous Australians – rheumatic heart disease.

Then, two-thirds of the way into it, everything changed. After all her clinical and research training in a biomedical system, O’Brien underwent a kind of academic and cultural awakening in terms of Indigenous health and the problems with what the researchers describe as an overwhelmingly “colonial” health system.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare tells us that the median age at death for Indigenous Australians with rheumatic heart disease is 43, with half of those who died aged under 45.

“Karen [Adams] and I began talking about the paradigmatic clash between biomedicine and Indigenous health,” she says. “What I needed to learn is, how do we make our very colonial hospital and medical systems appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“I’m Aboriginal myself, but I'm new to Indigenous research. I’m only now learning and trying to apply new ideas in an Indigenous research paradigm.”

Evolution to an Indigenous paradigm

Dr O’Brien’s mentor towards this new direction is Professor Karen Adams, Director of Gukwonderuk, the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences’ Indigenous engagement unit. Together, they’ve written a (as yet unpublished) paper titled Taking on Colonial Institutions: Making Room for an Indigenous Research Paradigm in Prospective Biomedical Research in Tertiary Hospitals.

“She helped me to reflect on how the project necessarily evolved from the biomedical into one more in keeping with an Indigenous paradigm,” Dr O’Brien says.

The “Indigenous paradigm” ideas are being applied directly in O’Brien’s study into using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify inflammation in the hearts of people with acute rheumatic fever. Participants for the study are being recruited now from Darwin, Alice Springs and Cairns hospitals.

“We still don't really know whether everyone gets inflammation of the heart with rheumatic fever,” she says. “Are there people whose hearts are not affected? We don't think so, but that's what we're trying to prove with this study. Some of the sequences on MRI can pick up even low levels of inflammation that wouldn't be evident in the blood tests, on the ECG, or heart ultrasound.

“We’re hoping that cardiac MRI will be able to differentiate between someone who has rheumatic fever and someone who doesn't, removing the need for the ‘possible’ and ‘probable’ rheumatic fever diagnoses that we currently use.”

Benefits of antibiotic injections uncertain

Rheumatic fever is treated with a monthly regime of antibiotic injections to prevent further episodes occurring, and therefore reduce the risk of progression to rheumatic heart disease.

When children have “definite” rheumatic fever, the benefit from these injections is clear. However, about half the time, it’s uncertain that it’s rheumatic fever causing the symptoms.

In case it is, the monthly antibiotic injections are prescribed. These are painful, and require frequenting health services, often hospitals, where Indigenous Australians unfortunately are still not guaranteed culturally-safe care – all for injections they may not even need.

Read more: Mental health and wellbeing: Listening to young Indigenous people in Narrm

Australia has one of the highest reported rates globally of rheumatic heart disease, where it’s overwhelmingly found in remote Indigenous communities. It’s caused initially by a contagious group A streptococcus bacteria that spreads more easily in overcrowded conditions without much in the way of healthcare or health services.

Researchers think there’s a genetic vulnerability at play, as well as the poverty and poor living conditions that stem from the enduring effects of colonisation.

“Two or three weeks after the strep infection is when kids and young people will get fevers and sore joints; they can get chest pain or a racing heart. They can get involuntary movements. That’s all the rheumatic fever.

“All of that can resolve with no long-term effects, except for the heart, and that’s where you can get rheumatic heart disease as a complication of the acute rheumatic fever.”

Rheumatic fever still on the rise

Rates of rheumatic fever appear to be increasing, O’Brien says, despite decades of government-funded research into it.

“But we still have high rates in a discrete population. Like most colonised high-income countries, we have the money for research, but we have such inequity and such disadvantage in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations that we still have the high rates that aren’t seen in many other countries anymore.

“Since the 1990s, rheumatic fever virtually only occurs in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It's not only regional and remote areas either – in urban Alice Springs, rates remain very high.”

Therefore, as an “Indigenous paradigm” reflects, anything to do with rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease must be innately Indigenous-focused.

“We talk a lot about household crowding and socioeconomic disadvantage,” says Dr O’Brien, “but we need to get better at acknowledging the role that colonisation continues to play when these occur in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.”

Read more: In rural and remote healthcare, investing in the workforce isn’t enough

Making our health system more culturally safe would play a significant role in eradicating rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease for good. Targeted improvements in health services buildings and locations, accessibility, language, transport, and cultural safety training for staff are needed.

Most important is increasing the Indigenous health and research workforce, and addressing the high turnover of healthcare staff in remote Australia.

“Karen and I talk a lot about how an Indigenous paradigm is relational,” Dr O’Brien says. “What actually works is a relational approach of having a doctor, health practitioner, or a nurse that patients trust, that they know, the longer probably the better. This way places all the value on that relationship, on that connection.”