It’s humbling – and possibly a bit challenging – to learn that you’re mostly microbe. There are at least as many bacterial cells – most of them in your gut – as there are human cells in your body. And the 23,000 genes on your genome are hardly a match for the 3.3 billion genes your microbiome collectively possesses.

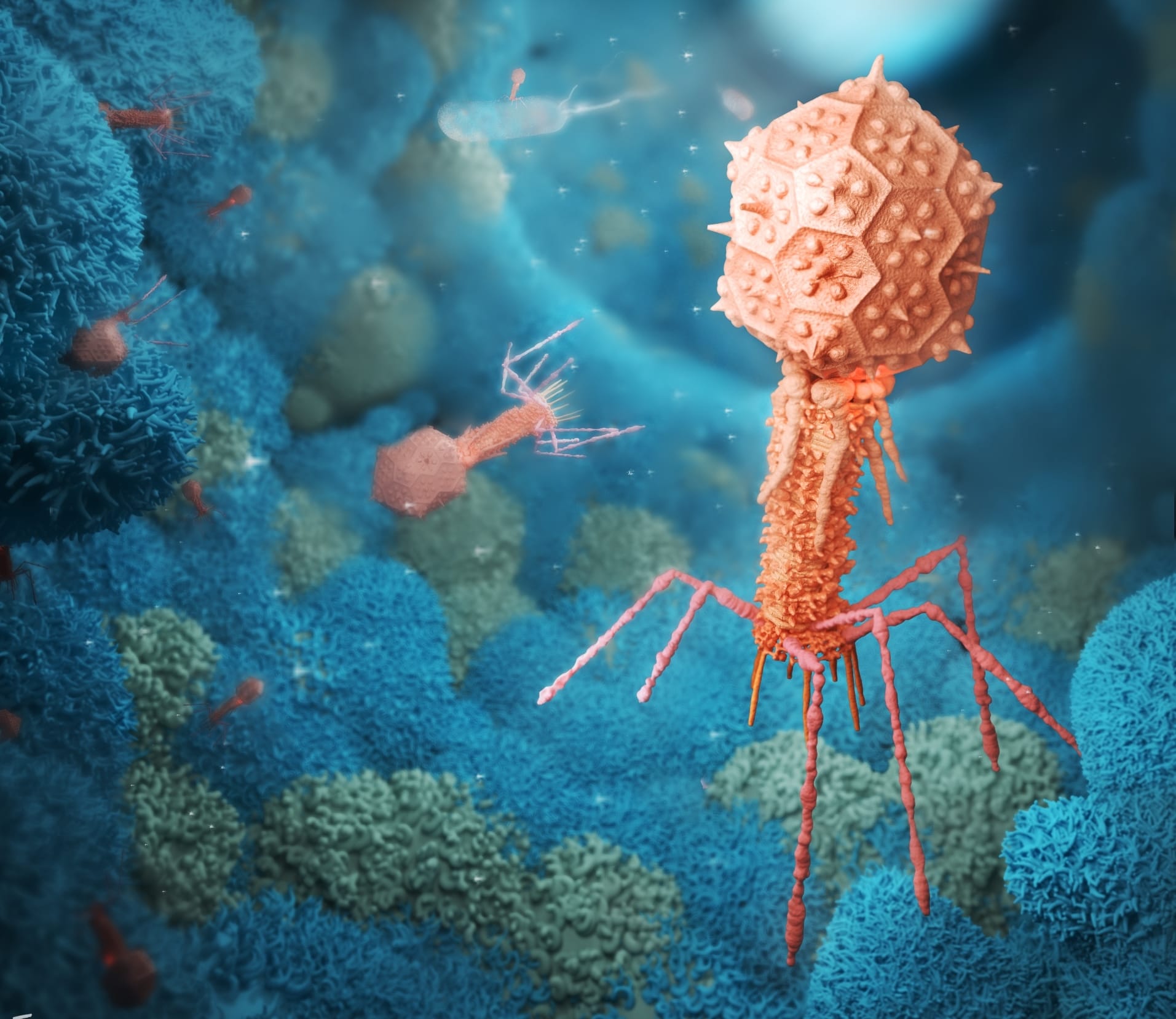

But the strange story doesn’t stop there. Crank up the resolution on your electron scanning microscope a notch and prepare to have your mind blown again. There’s another massive community lurking in you, the bacteriophages, or ‘phages’ for short. And if you aren’t fazed by your microbiome, you might be by your phages: they outnumber our resident microbes by another factor of 10, meaning you harbor 100 phages for every human cell in your body.

Watch the latest episode of A Different Lens: Beating the Superbugs

Phages, whose name is derived from Phagein, Greek for “eat”, were first discovered around the time of WWI and were successfully used to combat various bacterial infections including dysentery and cholera.

The history and use of phages in WWI is described in The Invisible War, a multiple award-winning graphic novel co-authored by Jeremy Barr along with Gregory Crocetti, Briony Barr, Ailsa Wild and Ben Hutchings, published by Scale Free Network.

Set in the trenches of World War I, featuring dysentery-ridden nurses, warring microbes and heroic phages, the reader is taken on a rollicking journey into the human body to witness war on a sub-microscopic scale.

When remembering our troops, doctors and nurses this Anzac Day, consider also tipping your hat or your glass to the vital role bacteriophages play in our world.

Watch: More on the inspiration behind The Invisible War story

Interest in phages waned with the advent of antibiotics (around WWII), which were much easier to apply. But now, with antibiotic resistance looming on the horizon and vastly improved gene sequencing technology available, phages are once again on the research agenda. Resident phage expert Jeremy Barr shares some highlights of these fascinating creatures.

Ten fun facts about phages

World: A centennial field guide to Earth’s most diverse inhabitants, by Forest Rohwer, Merry Youle, Heather Maughan and Nao HIsakawa.

1. Phages are the most abundant biological entity on the planet – at an estimated population of 10^31 (10 million trillion trillion), there are more phages on Earth than every other organism, including bacteria, combined.

2. Phages are also the most diverse entity on the planet – there are millions upon millions of varieties of phage, in different shapes and sizes, that infect millions of species of bacteria, most of which we don’t even know about yet.

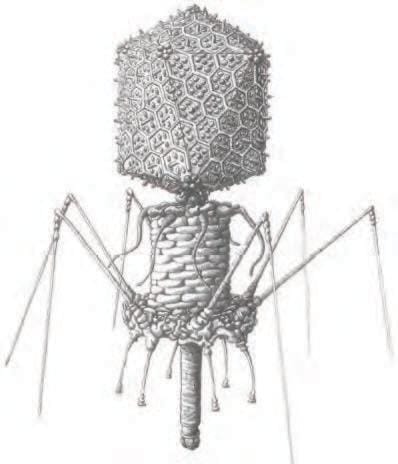

3. Are phages alive? The jury’s still out; they’re organic nanomachines that contain DNA or RNA and can self-assemble, but they have no intrinsic source of energy and cannot reproduce outside a host.

4. Phages are tiny – at 24 to 200 nanometers they’re 10 to 100 times smaller than the average bacterium, much too small to see with an ordinary light microscope.

5. We absorb about 30 billion phages into our bodies every day. They form an integral part of our microbial ecosystem. In Dr Barr’s tissue culture experiments, phages were shown to pass unchanged through every kind of human cell investigated.

We absorb about 30 billion phages into our bodies every day.

6. All the phage’s genetic material is squeezed under enormous pressure - up to 50 atmospheres - into a protein shell called a capsid, which usually takes the form of an elongated icosahedron (a shape with 20 equilateral triangular faces). When the phage lands on a host bacterium, this material shoots like a bullet into the interior of the cell.

7. Phages cause a collective trillion trillion successful infections per second, in the process destroying up to 40 per cent of all bacterial cells in the ocean every single day.

8. Researchers have suggested that ocean phages may turn over as much as 150 gigatons of carbon per year. But because we know so little about them, they’re not included in global climate models.

9. Scientists can currently only identify ~10-20 per cent of the genes in a given phage. That means 80 to 90 per cent of the genes have never before been seen. Phage genomes evolve extremely rapidly, and scientists think there’s a huge amount of gene transfer between phages, bacteria and eukaryotic cells.

10. All of the basic molecular biology tools that are used every day in the lab – DNA polymerase, restriction enzymes, CRISPR – came from phage research. But when US president Richard Nixon declared the ‘War on Cancer’ in 1971, microbiologists followed the funding, and phage research in the West stalled.

Read more: Doctor calls on medical profession to use phage therapy to tackle antibiotic resistance