Most of the incredible diversity of life on Earth is yet to be discovered and documented. In some groups of organisms – terrestrial arthropods such as spiders and scorpions, marine invertebrates such as sponges and molluscs, and others – scientists have described fewer than 20% of species.

Even our knowledge of more familiar creatures such as fish and reptiles is far from complete. In our new research, we studied 1034 known species of Australian lizards and snakes, and found we know so little about 164 of them that not even the experts know whether they’re fully described or not. Of the remaining 870, almost a third probably need some work to be described properly.

Documenting and naming what species are out there – the work of taxonomists – is crucial for conservation, but it can be difficult for researchers to decide where to focus their efforts. Alongside our lizard research, we have developed a new “return on investment” approach to identify priority species for our efforts.

We identified several hotspots across Australia where research is likely to be rewarded. More broadly, our approach can help target taxonomic research for conservation worldwide.

Why we need to look at species more closely

As more and more species are threatened by land clearing, climate change and other human activities, our research highlights that we’re losing even more biodiversity than we know.

Conservation often relies on species-level assessments such as those conducted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, which lists threatened species. Although new species are being discovered all the time, a key problem is that already-named “species” may harbour multiple undocumented and unnamed species. This hidden diversity remains invisible to conservation assessment.

One such example are the Grassland Earless Dragons (Tympanocryptis spp.) found in the temperate native grasslands of southeastern Australia. These small, secretive lizards were grouped within a single species (Tympanocryptis pinguicolla) and listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List.

But recent taxonomic research split this single species into four, each occurring in an isolated region of grasslands. One of these new species may represent the first extinction of a reptile on mainland Australia, and the other three have a high probability of being threatened.

Read more: Why we're not giving up the search for mainland Australia's 'first extinct lizard'

Scientists call documenting and describing species “taxonomy”. Our research shows the importance of prioritising taxonomy in the effort to conserve and protect species.

Taxonomists at work

Many government agencies do take some account of groups smaller than species in their conservation efforts, such as distinct populations. But these are often ambiguously defined and lack formal recognition, so they’re not widely used. That’s where taxonomists come in, to identify species and describe them fully.

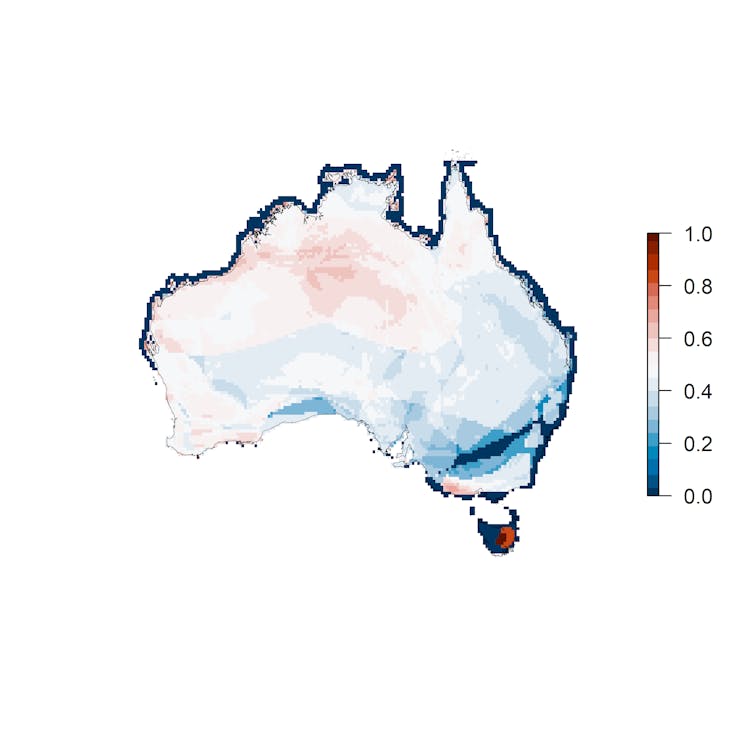

Our new research was a collaboration of 30 taxonomists and systematists, who teamed up to find a good way of working out which species should be a priority for taxonomic research for conservation outcomes. This new approach compares the amount of work needed with the likelihood of finding previously unknown species that are at risk of extinction.

The research team members, who are experts on the taxonomy and systematics of Australia’s reptiles, implemented this approach on Australian lizards and snakes. This group of reptiles is ideal as a test case because Australia is a global hotspot of lizard diversity – and we also have a strong community of taxonomic experts.

Australia’s lizards and snakes

Of the 1034 Australian lizard and snake species, we were able to assess whether 870 of them may contain undescribed species. This means we know so little about the remaining 164 species that even the experts couldn’t make an informed opinion on whether they contain hidden diversity. There’s so much still to learn!

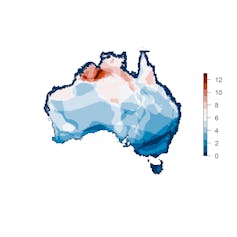

Of the 870 species experts could assess, they determined 282 probably or definitely needed more taxonomic research. Mapping the distributions of these species indicated hotspot regions for this taxonomic research, including the Kimberley, the Tanami Desert region, western Victoria, and offshore islands (such as Tasmania, Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands). Some areas in the Kimberley region had more than 60 species that need further taxonomic research.

We found 17.6% of the 282 species that need more taxonomic research contained undescribed species that would probably be of conservation concern, and 24 had a high probability of being threatened with extinction. Taxonomists know that there are undescribed species because there is some data available already, but the description of these species – the process of defining and naming – has not been done.

These high-priority species belong to a range of families including geckos, skinks and dragons found across Australia.

The high number of undescribed species, especially those with significant likelihood of being endangered, was a shock to even the experts. The IUCN estimates only 6.3% of Australian lizards and snakes require taxonomic revision, but this is obviously a significant underestimate.

A race against extinction

Beyond lizards, there’s a huge backlog of species awaiting description.

Recent projects have used genetic analyses to discover unknown species, including a $180 million global BIOSCAN effort aiming to identify millions of new species. However, genetics is only a first step in the formal recognition of species.

The taxonomic process of documenting, describing and naming species requires multiple further steps. These steps include a comprehensive diagnostic assessment using a combination of evidence, such as genetics and morphology, to uniquely distinguish each species from another. This process requires a high level of familiarity and scholarship of the group in question.

Among the Australian lizards and snakes alone, there’s a backlog of 59 undescribed species for which only the final elements of taxonomic research are awaiting completion.

To work through these taxonomic backlogs – let alone species that are so far entirely unknown – resources need to be invested in taxonomy, including research funding and increased provision of viable career paths.

Without taxonomic research, the conservation assessment of these undocumented species will not proceed. There are untold numbers of species needing taxonomic research that are already under threat of extinction. If we don’t hurry, they may go extinct before we even know they exist.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.