“We say sorry.”

With just three words, then-prime minister Kevin Rudd said in 2008 what his predecessor wouldn’t say in Parliament.

And so swelled the tears, emotion and silent pain of generations of Indigenous Australians who looked on from the gallery above, together with those glued to the broadcast all over the country.

Sometimes words really do matter.

But this significant step towards Indigenous reconciliation in Australia didn’t occur in a vacuum. Sometimes our discourse – our narratives of disadvantage, freedom, hope and fear – take on a momentum all their own.

Read more: Forgiveness requires more than just an apology. It requires action

Can discourse be quantified?

But demonstrating this momentum is hard.

The federal election is a case in point. Indigenous people tell us time and again that First Nations concerns are often excluded from the public conversation. Major surveys suggest many voters don’t seem to care.

But what if we could quantify our discourse? What if we could apply statistical tools to chart trends, shifts and deflections in our national narrative regarding First Nations issues? What would we learn?

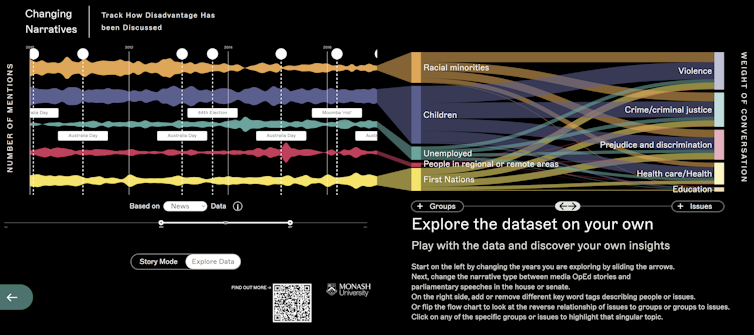

To answer these questions, we analysed more than 82 million words of Australian public discourse. We obtained nearly 500,000 Australian news and opinion articles from 1986 to 2021, and filtered these down to 143,923 pieces speaking to broad issues of disadvantage in Australia. You can explore the data for yourself in our interactive dashboard.

So what did we find?

Discourse momentum and the Apology

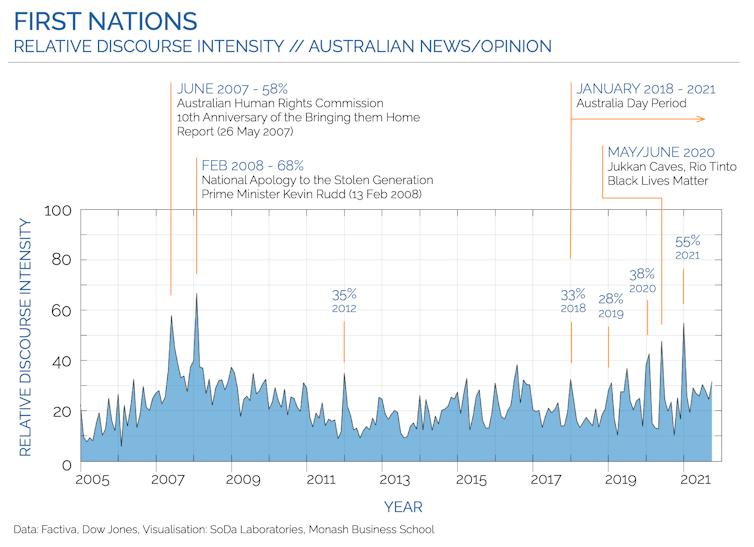

Our analysis revealed the relative attention our news and opinion pieces gave to First Nations peoples began to grow steadily from about 2005, with a huge peak (58%) in May 2007 coinciding with the 10th anniversary of the Australian Human Rights Commission’s Bringing Them Home report, which was about the Stolen Generations.

This peak was followed in February 2008 around the Apology itself. Remarkably, in that month, more than two-thirds (68%) of the news and opinion pieces that spoke to issues of disadvantage referred to First Nations peoples.

You can see from the chart above that the Apology was almost like a pressure valve being released. The relative share of First Nations discourse dropped steadily thereafter, bottoming out in 2012 – just in time for the protests of 2012 regarding Australia Day, or what many First Nations people call Survival Day or Invasion Day.

But we can also see that in the past few years, First Nations discourse is once again on the move. Like arms being lifted to the air, First Nations’ discourse share in our public media is rising.

Some peaks speak to external triggers – Rio Tinto’s destruction of the sacred, 46,000-year-old Jukkan Caves (May 2020), followed in quick succession by Australia’s own Black Lives Matter marches (June 2020), both stand out.

But then there’s also a metronomic drum beat visible in our recent First Nations discourse.

The beat’s name? January.

When we talk about First Nations – and when we really don’t

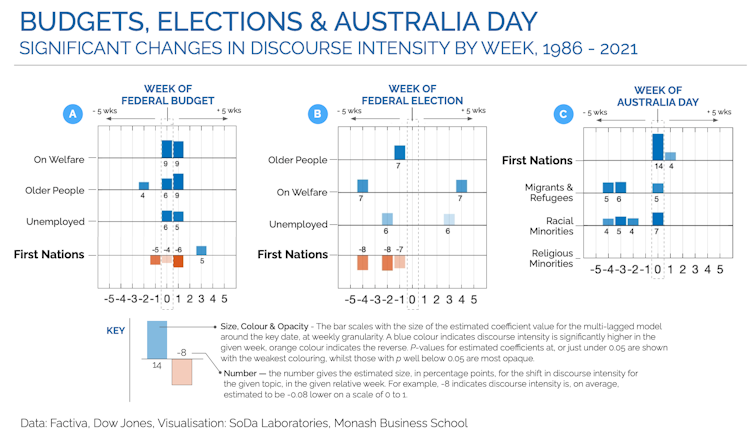

To further explore these trends, and put some stronger statistical basis to our initial findings, we undertook a second form of analysis.

This time, instead of simply eyeballing line-plots, we used models that can uncover significant shifts in relative narrative intensity regarding certain key events in our national conversation.

Specifically, we fed in the exact date of federal budget night, and the federal election, dating back to 1986, and added to these dates the annual Australia Day/Invasion Day date across all years (26 January).

The models we used effectively ask: “Did the relative share of First Nations discourse in Australian news and opinion change significantly during this week?”

To give some context, we also checked whether our discourse relating to a range of other groups shifted, and widened the search to the five weeks before and after these key events.

If anything, our work stands right behind Indigenous voices who’ve been saying the same thing for years.

Over the past four decades, in the weeks leading to the federal budget and the election, Australian news and opinion talks relatively, and statistically significantly, less about First Nations peoples than at other times of the year.

The magnitudes may seem small (-6 to -8%), but these should be read against the background of average First Nations discourse intensity of about 20%.

So the deflection to our normal discourse is, in fact, very large, comprising a 25-50% decline against the baseline.

In collaboration with Paul Ramsay Foundation, Monash University researchers have created an interactive visualisation system to showcase the data and analysis resulting from this research. The visualisation allows visitors to read data-driven stories about narratives of disadvantage discussed in the Australian media and Parliament over recent decades.

So what of the January bump?

Without question, the biggest single deflection we uncovered in our national discourse was towards First Nations during the week of Australia Day/Invasion Day each year – a huge 14% point climb during the week, and 4% in the week after.

But our results broadened the conversation. Not only do we discuss First Nations more at Australia Day/Invasion Day, we also significantly expand our share of discourse for migrants, refugees, and racial minorities.

It seems 26 January is the closest Australia has to a national discourse of identity day. In effect, we collectively ask: “Who are we, and where have we come from?”

A new day

With a new government comes new opportunities.

With the Albanese Labor government committing to significant progress on the Uluru Statement from the Heart, coinciding with a new grassroots campaign to build support for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, the indications are there that 2022 may see a significant shift in our national discourse.

We were surprised then, when we checked our most recent data.

First Nations discourse share in our national news and opinion flatlined during the weeks leading into the election campaign.

Granted, this was an improvement on the significant negative shift in First Nations discourse share the models had uncovered over the past decades.

However, for the week starting Monday, 23 May, two days after the election, something remarkable happened in our discourse – First Nations share doubled from 14% over the week of the election, to over 31%.

What a difference a new week can bring.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.