Australia is finally beginning a mass vaccination campaign against COVID-19. It’s been a moment many have been looking forward to, but it’s also an occasion to reflect on the important yet limited role this type of immunisation plays in the pursuit of public health.

When it comes to safeguarding communities’ wellbeing, vaccines (as distinct from inoculations, which date to 15th-century China at the latest) are a recent, expensive and modest part of the process.

Since their introduction in the 19th century, they've certainly helped to improve birth rates and reduce mortality and morbidity rates, and as such enabled populations around the globe to grow.

But vaccines have a narrow scope, and the high costs of developing new ones render them vulnerable to funding shortages in both the public and private sectors. Most human societies, most of the time, fight infectious diseases and numerous other hazards by relying on simple methods of avoidance and harm-reduction, such as filtering water, zoning, waste disposal, and using protective gear.

The current pandemic is no exception. Apart from testing, administering the COVID-19 vaccine is the first major instance in which governments and healthcare providers will be making use of a complex biomedical product.

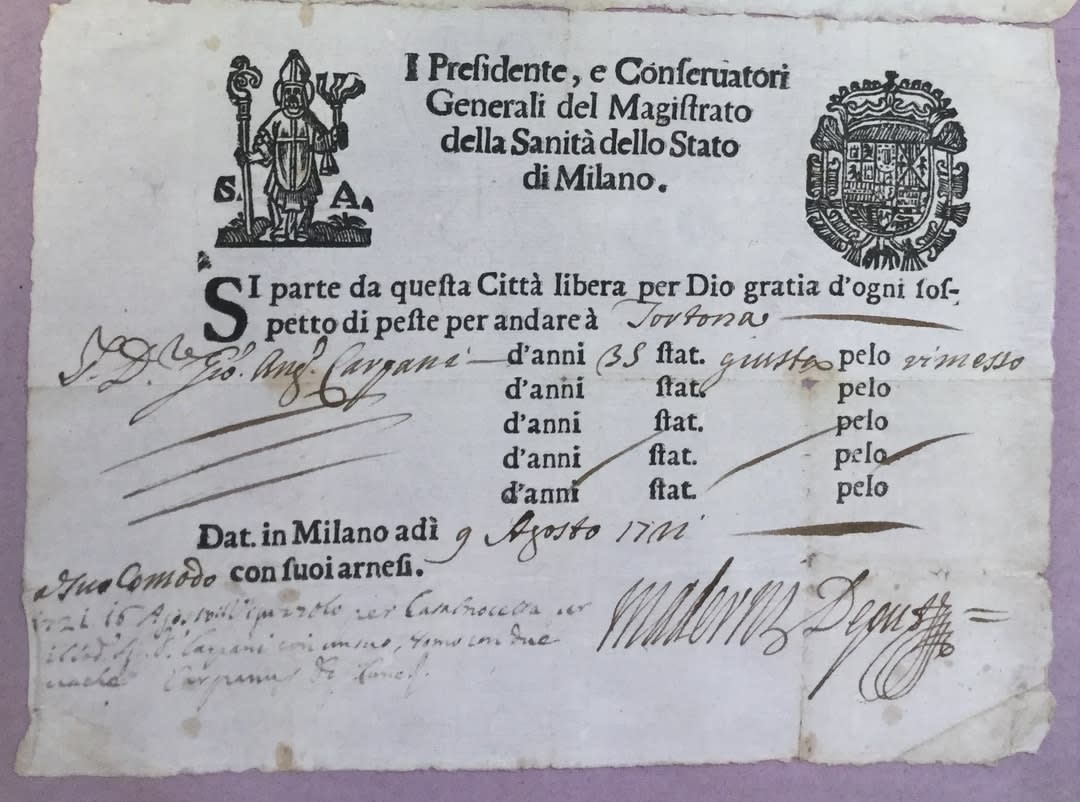

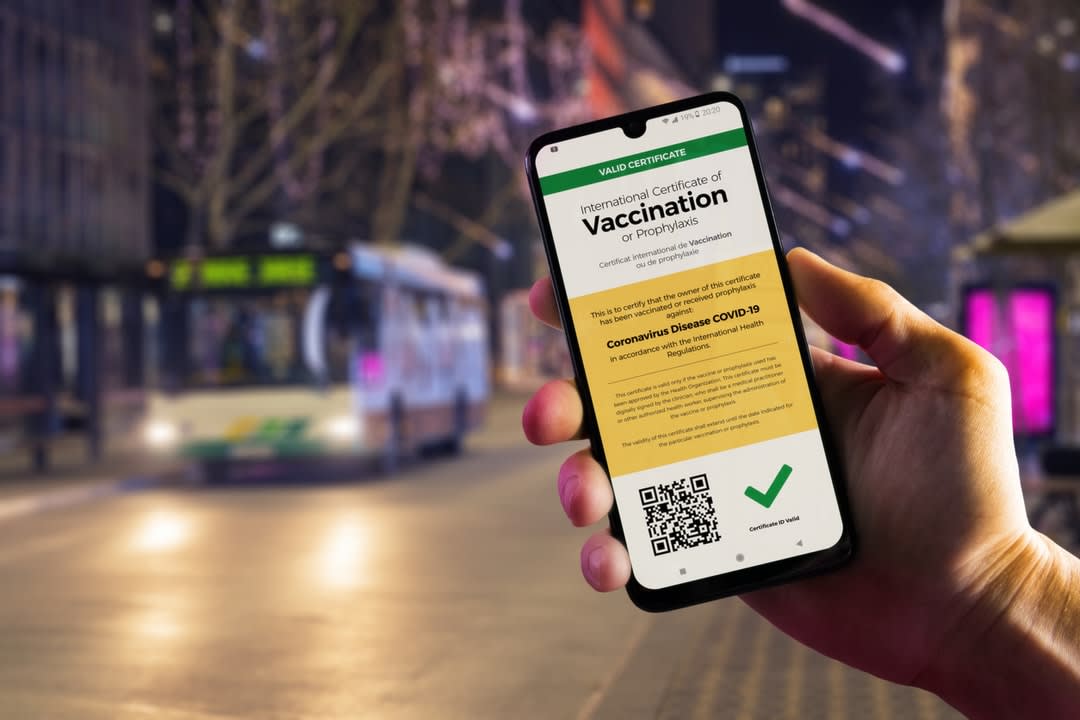

For more than a year, while data was being gathered and analysed, and vaccines synthesised and trialled, the country relied on prophylactic methods that date back hundreds, if not thousands, of years – physical distancing, travel bans, hard perimeters, curfews, quarantine, mask-wearing, and hand-washing. And once vaccination begins in earnest, the requirement to present a clean bill of health will likewise date back at least to the introduction of health passports in 16th-century Europe.

Image: Archivio di Stato di Alessandria, Comune, III, 2181 (supplied by author).

To be sure, none of the measures we’ve been practising are watertight, and each came at a price – economically, emotionally, physically and politically. Nor were they equally burdensome or beneficial to everyone. Far from it.

But collectively, non-biomedical or “low-tech” prevention, alongside the cultivation of civic solidarity, saved numerous lives every day, and at a fraction of the cost of curing the sick and developing and distributing vaccines, to say nothing of the inestimable agony of premature death.

The success of simple preventive measures, even in wealthy welfare states like Australia, should not be taken for granted. Without resources to keep un- or less-employed people from losing their homes or spiralling into debt, without medical infrastructures that are both excellent and accessible, and without informed leadership and a strong sense of mutual responsibility, any of these robust methods would be insufficient.

The rich, democratic global north has furnished us with too many examples of how shortcomings in one field literally nullified advantages in others.

But when such cohesion exists, examining our diverse hygienic pasts is essential for at least two reasons.

First, as the past year has demonstrated, excluding prophylactic methods because they were developed before or outside the context of modern medicine, Euro-American biomedicine can actually be detrimental to saving lives.

In COVID’s early days, a New York Times op-ed, among other observers, described some Asian governments’ recourse to quarantine and travel bans as "medieval". It wasn't meant as an endorsement. Twelve months later, such "barbaric" measures, having saved millions of lives around the world, are part of a "holistic strategy", striking a reassuringly modern sound.

Knowledge of hygienic pasts

Knowing more about communities’ hygienic pasts is practical in a second sense. Experiences of health and disease are culturally-specific, and people’s shared memories of health-related and other forms of trauma are an important part of what shapes their approaches to curing and preventing illnesses.

Governments and organisations seeking to impact diverse constituencies benefit from being able to tap into their pasts and understand communities on their own terms. A lockdown, for instance, is a difficult experience for most people, but there are those for whom it conjures particularly negative memories, such as living under an oppressive regime, war, or an ethnically-biased intervention.

That 's not a reason to avoid implementing such measures, but communicating about it to different audiences in appropriate ways is crucial, and often best led by local organisations and governments.

To offer a second and final example: Billions of people around the world have different ideas about disease transmission and resilience dating back millennia, and don't draw a clear line between physical and moral wellbeing. Addressing their concerns during a global pandemic in purely biomedical terms risks lowering their motivation to comply with preventative measures.

At worst it can be entirely counter-productive and lead to dismissing the gravity of a situation, at least as seen by others, shirking civic duties and inaccurate or under-reporting of symptoms.

Understanding communities’ deeper hygienic pasts makes it easier to communicate across cultural divides, and to the benefit of society at large.

Once again, understanding communities’ deeper hygienic pasts makes it easier to communicate across cultural divides, and to the benefit of society at large.

Looking forward, vaccines are not a panacea for COVID-19, not to mention its emerging variants and mutations. And if globalisation is the normalcy many people continue to crave, the likelihood of fast-spreading viruses will remain high.

Historians aren't in the business of predicting the future, but they're on firm ground to point out that the dream of eradicating all infectious diseases was, and remains, just that. Until it’s realised, we'll continue to rely for much of our health on an arsenal that's tried and true, but one that works best when its efficacy is acknowledged and appropriately explained.

Guy Geltner leads the ERC-funded project Healthscaping Urban Europe, 1200-1500. Follow the group on Twitter: @prosanitate.