2020 was a year when our politicians and the press were preoccupied with the pandemic, and rightly so. However, for most young people the climate crisis has remained a persistent and uncomfortable reality.

Growing up in a time of climate crisis has been shown to have serious consequences for mental health and well being for many children and young people. These impacts did not reduce in 2020 but rather COVID-19 added another layer to their anxieties. Yet, even so, as we emerge from the restrictions of the pandemic, it seems that young people are again ready to lead the revolt and demand attention be returned to the climate crisis.

Thousands of students chanting at #ClimateStrike today @theage pic.twitter.com/gIc7PYjrbS— Anna Prytz (@annaprytz) May 21, 2021

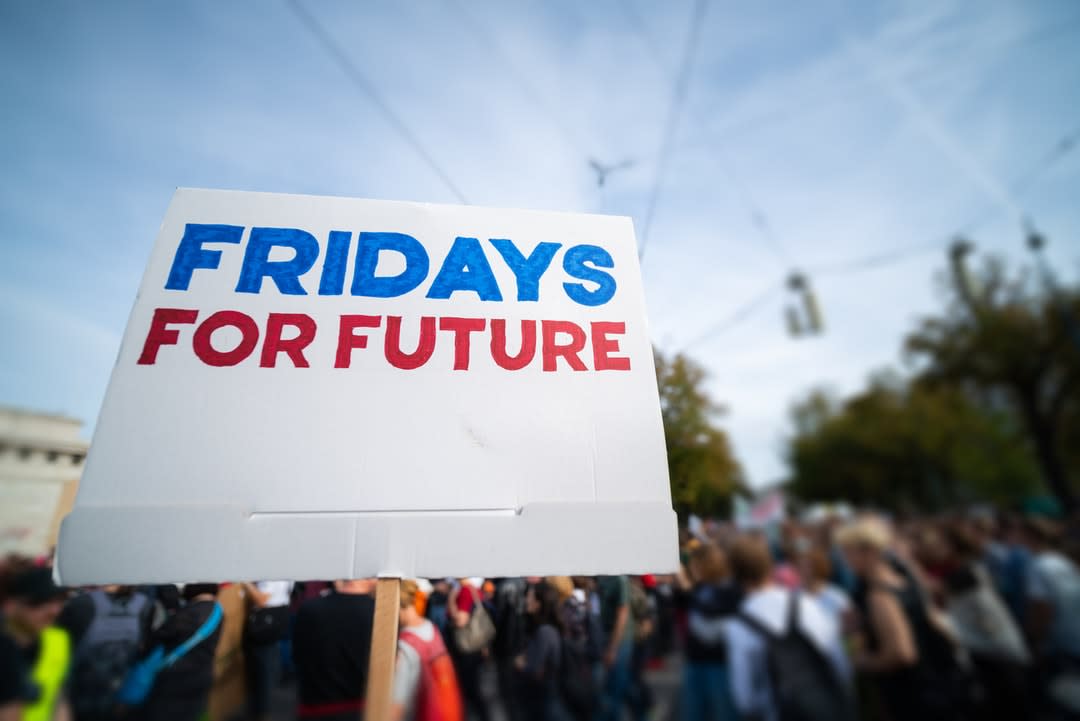

The School Strike 4 Climate movement, which happened across Australia on Friday, was initiated in 2018 and made famous by the activism of Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg. In Australia, hundreds of thousands of young people have previously joined these protests as an outlet for their concern and dissatisfaction with the political responses to the climate crisis.

For students who walked out of classes, these protests are about extending their voices beyond the stifling grasp of schools. In effect, young people’s activism is a spill-over phenomenon that escapes the bounds of schooling itself, even if it is just for one day.

How can school leaders hope to authentically engage with this imperative? After all, educational systems, arguably bastians of the status quo, are one of the many institutions that have helped sleepwalk us into the climate crisis we face.

'... It is time for school leaders to recognise that young people exercising their democratic rights are citizens, and not citizens-in-waiting.'

Education policy and the hidden curriculum of individualised hyper-competition and student docility on which typical teaching practice hinges are pathways to job-ready graduates rather than active and engaged citizenry that are vociferous in their environmental concerns. Yet, young people are no dupes.

For school leaders this perhaps is a moment to more radically understand what student voice is. While experts like Pasi Sahlberg have argued that schools and governments need to support students in their strike action, school leaders are clearly caught in a delicate balancing act between supporting students, managing the perceived expectations of their school community and wider public, and meeting their bureaucratic obligations.

However, if there is hope to escape the schoolification of the voices of young people, then one obstacle to be overcome is how school leaders set limits on student agency when thinking through routinised notions of ‘student voice'.

Narrow framings of what otherwise could be seen as an active participation in democracy constructs distinct spatial and temporal boundaries.

For example, some have argued that activism doesn’t belong in schools, or that protests should be conducted on weekends so as to not disturb students’ learning of prescribed curriculum.

Like politicians who suggest that ‘during the school time kids should be in school’, school leaders might likewise think about student voice through the lens of the current arrangements in their schools. The framing of young people’s civic activism through these school-based perspectives sets normative boundaries within which rebellion can be more comfortably, if not tokenistically, contained. In this sense, as sociologists have long understood, who frames wins.

Let’s be honest, as a form of civic engagement, the climate strikes are a political act of disobedience. Climate strikes aren’t about asking permission, but interrupting the everyday. In effect, striking is not just about ‘expressing feelings’ but also about blocking supply. In this calculation, if you don’t ruffle any feathers then you’re not doing it right.

So what now for school leaders?

Maybe it is time to recognise that we are in a common fight for the survival of our civilisation. It really is that dire.

Yet, beyond this urgency, it is time for school leaders to recognise that young people exercising their democratic rights are citizens, and not citizens-in-waiting. And further still, for young people it is more than an act of political citizenship, it is an act of self-preservation.

Instead of giving in to despair, despondency and resignation, young people are finding their voice and agency. The activism of young people needs to be understood in these broader terms, across broader terrains and beyond timetables.

Supporting young people to speak up, take action and make a difference must be a priority for educators. For school leaders, to do any less, is to fail the moral test of our times.

This article was co-authored with Dr Brad Gobby, a senior lecturer at Curtin University.