This year’s COP27 meeting in Egypt is being heralded as an “implementation COP”, where countries need to stop debating targets, and instead focus on developing real plans and timelines to reach previously agreed-upon targets.

The Albanese government will need to take rapid action to meet its pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, including phasing out Australia’s dependence on fossil fuels. It’s also recently committed to signing a global pledge to reduce methane emissions.

This latter pledge – to cut global methane emissions by 30% this decade – is an easier goal to reach than carbon dioxide emission targets, given methane is produced by fewer sectors.

Reducing methane will significantly slow climate change, as methane accounts for almost as much global warming to date as carbon dioxide does, according to the latest IPCC report.

Crucially, proven solutions already exist to rapidly reduce methane emissions in a lucrative way, and Australia is leading the world in developing ways to reach methane targets.

But we must act quickly to use already proven technologies, and rapidly adopt new ones, if we’re to meet the pledges.

The methane-making microbes

The answers to the globe’s methane problem lies in tackling microbes called archaea. Eighty percent of methane emissions are naturally produced by archaea, yet current farming and waste practices have greatly increased archaea numbers and activities. Whether in the stomachs of livestock or in landfill, they produce hundreds of millions of tonnes of methane each year.

My laboratory has studied the microbes responsible for methane cycling in all major industrial settings and natural environments where it is produced. This work has taken us to settings as diverse as livestock farms, natural wetlands, wastewater treatment plants, the Southern Ocean, geothermal springs, and even termite mounds.

Through our award-winning findings, we’ve uncovered a great deal about the archaea that produce methane and the bacterial counterparts that consume it, and shown their activities depend on complex ecological interactions. We’re now using these insights to work with the agriculture, waste, and energy sectors to reduce and recycle their emissions.

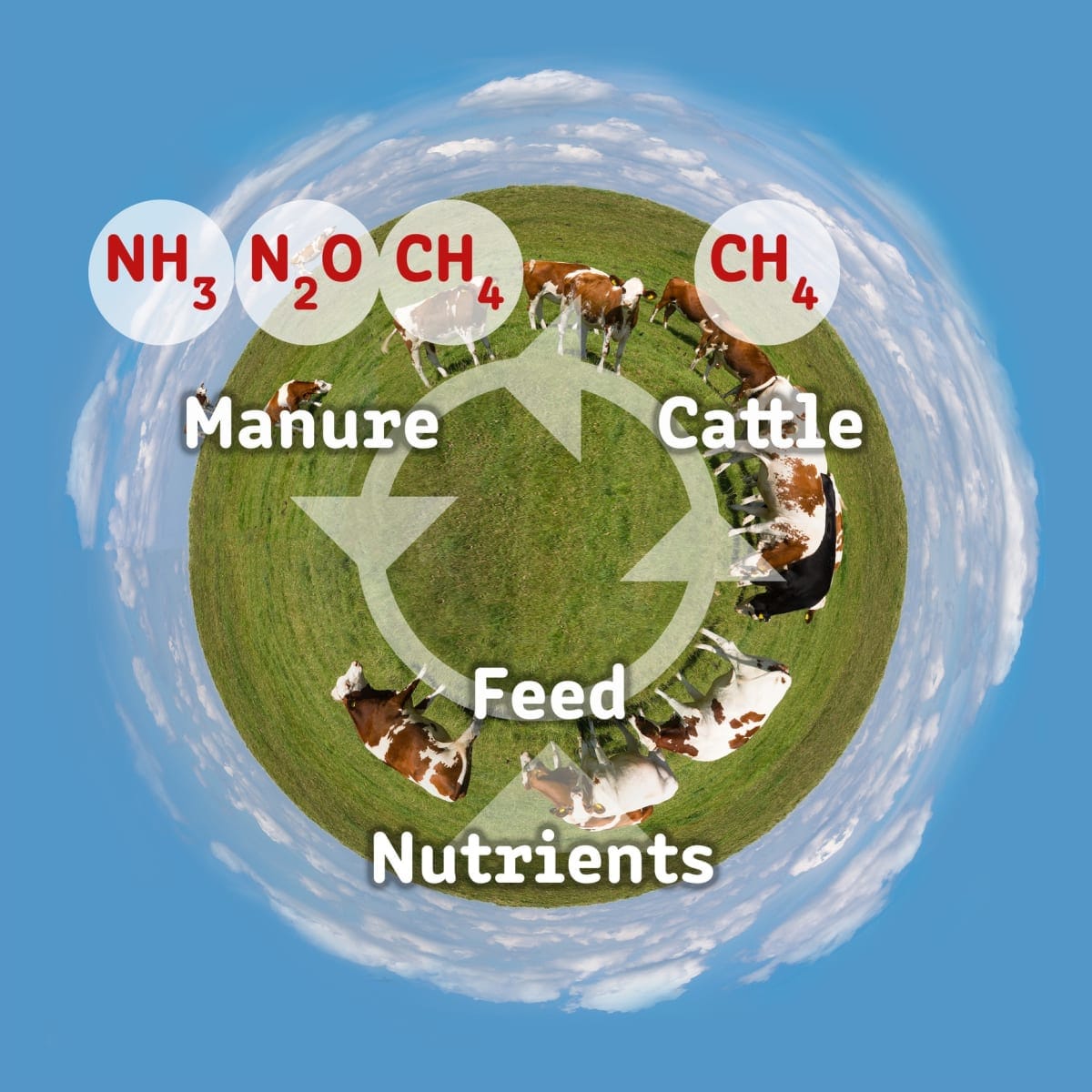

Strong solutions exist for Australia’s agricultural sector, which produces approximately half of Australia’s annual methane emissions. Simple chemical or seaweed-based feed additives can reduce methane emissions from ruminant livestock, such as cattle and sheep.

A Dutch company, DSM, has developed a feed additive called Bovaer that reduces methane production by up to 90% in Australian livestock. Essentially, it suppresses the enzyme that archaea use to make methane within the animal’s stomach.

Numerous field trials and more than 50 peer-reviewed articles have shown this feed is effective and safe in quantities as low as a quarter of a teaspoon per cow, per day. The feed is now available in multiple countries, including Australia.

Also promising is CSIRO’s FutureFeed, which uses an edible red seaweed called Asparagopsis to stop methane production.

Solutions closer to home

In my lab, we’re exploring ways to increase the effectiveness of these feeds. Normally, archaea feed on the hydrogen gas produced during the digestion of grains. However – in some animals that produce low levels of methane – we’ve shown that their microbes use this hydrogen to make desirable nutrients instead.

The holy grail is to develop a feed that redirects the hydrogen away from the waste gas methane and into these nutrients.

The end result? Less burps and farts, more muscle and milk. A win-win for the farmer, and we’re partnering with industry to help make this happen.

The end result? Less burps and farts, more muscle and milk. A win-win for the farmer.

For Australia to meet its methane emissions pledges, it must also tackle the high levels of methane emitting from coal mining, gas extraction, and waste treatment.

Transitioning our energy sector and reducing/recycling waste will help with this goal, just as it will in reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

A supporting solution is to capture some of the methane produced from these sources and recycle it into products.

For example, methane-consuming bacteria can convert emissions from the energy and waste sectors into nutritionally-rich pet and fish feeds. If scalable, this bit of Australia-led science would reduce the land, water, climate, and biodiversity impacts of current food production.

In July this year, Monash University, together with seven academic organisations and 22 industry partners, formed the ARC Research Hub for Carbon Utilisation and Recycling with $5 million federal funding. The aim is to develop technologies to transform greenhouse gas emissions from the energy, manufacturing, and waste sectors into valuable products.

Some of these technologies are already in field trials and are close to being scalable.

At Glasgow’s COP26 last year, Australia refused to commit to the global methane pledge, citing the impost on the agri-sector. The only way to reduce emissions, the former deputy prime minister said, was to “Go grab a rifle”!

If they’d looked, they’d have seen that Australia is at the forefront of developing technologies to make farming more environmentally-friendly, as well as improving agricultural production and quality.

At COP27 this week, Chris Bowen, the Minister for Climate Change and Energy, along with signing a methane pledge, can highlight Australian science, when the debate turns (as it must) to real and practical solutions to tackling climate change.