The Amazon is burning, and some contentious points need careful explanation.

- Brazil is just one of nine countries bordering the Amazon.

- There are fewer fires than in past years.

- Most of the fires are burning on land already cleared.

- Atmospheric oxygen will not disappear if the Amazon is lost.

- The Amazon is not home to the biggest rainforest fire burning today.

Commentators around the world, including myself, have sought the origins of French President Emmanuel Macron’s beautiful metaphor describing the Amazon as the world’s lungs, responsible for 20 per cent of its terrestrial oxygen. Here’s where it came from:

In 1939, Dr Harald Sioli, later the director at the Max Planck Institute for Limnology, boarded a coastal steamer and ventured into the Amazon, not leaving for another 19 years.

As Dr Elke Maier wrote in the Flashback_Topical Ecology article “Amazon Adventure”:

“In an interview in 1971, he prophesied that felling the tropical rainforests would lead to a rise in the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air. The Brazilian press promptly coined the phrase “green lungs of the planet”. The journalists ignored Sioli’s misconception that a forest in equal balance between the formation and decomposition of organic matter consumes just as much oxygen as it produces. Despite this, Sioli succeeded almost 40 years ago in raising public awareness of the importance of tropical forests for the climate.”

The claim that the Amazon produces 20 per cent of the world’s oxygen suggests its loss would lead to global hypoxia. The 20 per cent claim is certainly true, but the figure only applies to terrestrial oxygen. The Amazon represents one fifth of the world’s vegetation, so this is a reasonable estimate based on transpiration alone.

However, Brazilian Vice-President Hamilton Mourao was correct when he said the oxygen produced by the Amazon is small compared to that produced by the ocean. Studies show atmospheric oxygen has shifted little more than 0.71 from 21 per cent in 800,000 years. Oxygen produced by terrestrial rainforests is only about 1 per cent, hence the small shift over millennia.

An Amazon burning is a signal to refocus on our faltering planet, to take seriously the threats of climate change and habitat destruction.

Ultimately, this means the 20 per cent oxygen claim is true, but badly contextualised. The top five rainforests in the world are the Amazon Basin, the Congo Basin, the Valvidian, the Daintree and the Alaskan Tongass. Even if all were lost, atmospheric oxygen would remain fairly stable.

That said, Yale studies estimate the world’s rainforests absorb 25 per cent of all carbon emissions. According to the WWF, a world without the Amazon would leave another 140 years’ worth of anthropogenic carbon emissions in the atmosphere. This doesn’t include emissions from its actual burning.

As 2400 fires now blaze across the Amazon, the world is distracted from 7000 fires burning in Angola, 1000 in neighbouring Zambia, 3000 in the Congo, 800 in Australia and 550 in Indonesia.

We’re also distracted from the fires crackling across lands usually covered in ice, such as Greenland, Iceland, Alaska and Siberia. Roughly, the Amazon fires represent just 15 per cent of the world’s fires affecting areas close to African and Asia Pacific rainforests.

The Amazon burning has reminded the world of Dr Sioli’s original worries in 1971. Renewed global concern emerged mere months after the world was alerted to the dangers of a global mass extinction by 145 experts from 50 nations led by Professor Sandra Diaz, of the National University of Cordoba in Argentina.

The idea that a burning Amazon is trivialised by other fires around the world hardly dismisses but rather more forcefully underlines the need for a renewed focus on the issue of agricultural arson affecting the global biome.

Why is it that Brazil has been targeted even though there are nine nations bordering the Amazon Basin? The reason is that although Bolivia has had some attention in the media, Brazil covers 60 per cent of the Amazon.

Additionally, the new government has weakened ecological controls and actively encouraged fires lit by “rancheros”. Ecological management has fallen to the local community leaders who are invariably cattle owners themselves – a conflict of interest.

The idea that a burning Amazon is trivialised by other fires around the world hardly dismisses but rather more forcefully underlines the need for a renewed focus on the issue of agricultural arson affecting the global biome.

The government grants land claims on newly deforested areas if cattle are grazing on them. When he came to power on 1 January, 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro threatened to exterminate political rivals, wind back the powers of ecological NGOs, give “not one more inch” to indigenous peoples, and run a new highway through the middle of the Amazon. Hence the focus on Brazil.

The paltry $21 million offered by the recent G7 was little more than a token gesture, but this is likely because financial aid to governments often ends up in the bank accounts of the ruling elite rather than the issue at hand. The President has a personal history of being aggressive and financially motivated. According to the IMF, Brazil’s shadow economy is the highest of the nine Amazonian states at 35 per cent of GDP, second only to Bolivia, at 45 per cent.

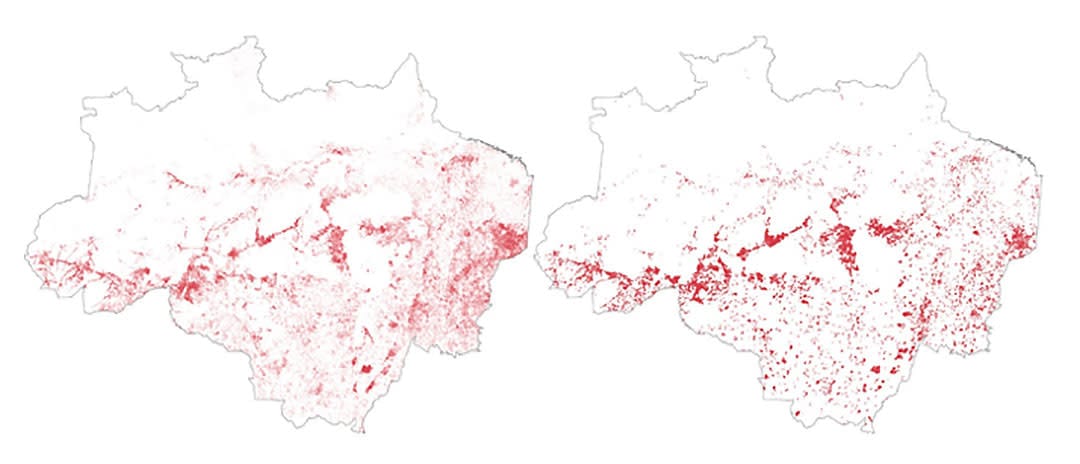

Figure 1. NASA Satellite images for August fires in the Amazon – 2011-2018 average (left) and 2019 (right). Source: NY Times, Aug 24 2019.

The next issue is that this year’s burning is by no means unprecedented. The Amazon is burnt every year as part of the quiemada, the 78,000 fires in 2019 so far dwarfed by 350,000 fires in 1987 when they took four months to extinguish. As the wet season arrives, the fires should dissipate close to Christmas. The height of the quiemada is August, hence recent global attention.

Bigger numbers of fires peaked in 2005 and 2010 under the former socialist president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, two years after Brazil’s liberation from a military dictatorship. These were drought-affected years due to El Nino, whereas this year is not; also, there have been few lightning strikes as a source of ignition.

Read more: Amazon fires: Could we reach the tipping point for runaway climate change?

From Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE), researcher Alberto Setzer confirms: “There is nothing abnormal about the climate this year or the rainfall in the Amazon region, which is just a little below average. The dry season creates the favourable conditions for the use and spread of fire, but starting a fire is the work of humans, either deliberately or by accident.”

Noteworthy also is that the number of fires is never a good estimate of actual size, usually assessed after the event. We can’t know the final impact as yet, although scientists at Brazil’s INPE calculated there were 35 per cent more fires so far this year than in the average of the past eight years.

While the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery group says the fires are mostly along adjacent tracts of land already cleared (as reported in the New York Times), this cannot be wholly true if deforestation (also measured by satellite) increased 88 per cent since last year.

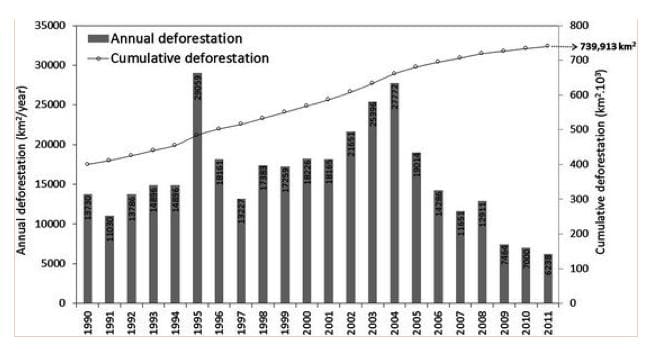

Figure 2. Annual deforestation rates and cumulative deforestation in the Brazilian Legal Amazon, 1990–2011. Source: Parro et al., 2012 DOI: 10.1007/978-94-007-4676-3_20

At present, only 0.62 per cent of the Amazon has been burnt since January 2019 – a seemingly small amount. But what’s more important is that the current president has weakened ecological protections for the Amazon, and reinvigorated deforestation for economic gain.

The cumulative amount of loss is the greater issue at hand for the world’s climate. For context, note the years with the highest fires don’t match up with the greatest deforestation in Figure 2.

In other words, the result can vary, and the number of fires ends up being immaterial compared to the areas affected. Note the loss up until 2012 represents 13.5 per cent of the Amazon. To 2019, the WWF now estimates that 17 per cent of the Amazon has been lost, so it is escalating.

On top of this, soil has degraded, especially levels of phosphorus derived from trans-Atlantic wind currents originating in the Sahara.

The AmazonFACE project monitored tree growth and leaf development above ground, and tracked root growth and activity within soils belowground. Regrowth has slowed dramatically, and the Amazon’s ability to absorb carbon emissions is expected to be halved by 2035.

Conclusion?

The Amazon will not be lost yet, but its continued exploitation under a new government has the potential to escalate. Sadly, short-term economic imperatives fail to see the long-term wealth that could be garnered on behalf of the Brazilian and neighbouring peoples. Although true that the Amazon is responsible for 20 per cent of terrestrial oxygen, its loss would not affect atmospheric levels released by the ocean. It would, however, affect climate emissions.

An Amazon burning is a signal to refocus on our faltering planet, to take seriously the threats of climate change and habitat destruction.

It’s not the number of fires that are important in any given year, but rather the cumulative destruction that rightfully has the world worried. This is especially important when almost every major rainforest system on the planet is being burned by people every year.

For the sake of younger generations, the world must find a way to properly repay the custodians of our shared planetary resources so they need not resort to destroying them. I think Dr Sioli would have agreed.

Dr Paul Read was a senior lecturer at Monash University at the time of writing this article.