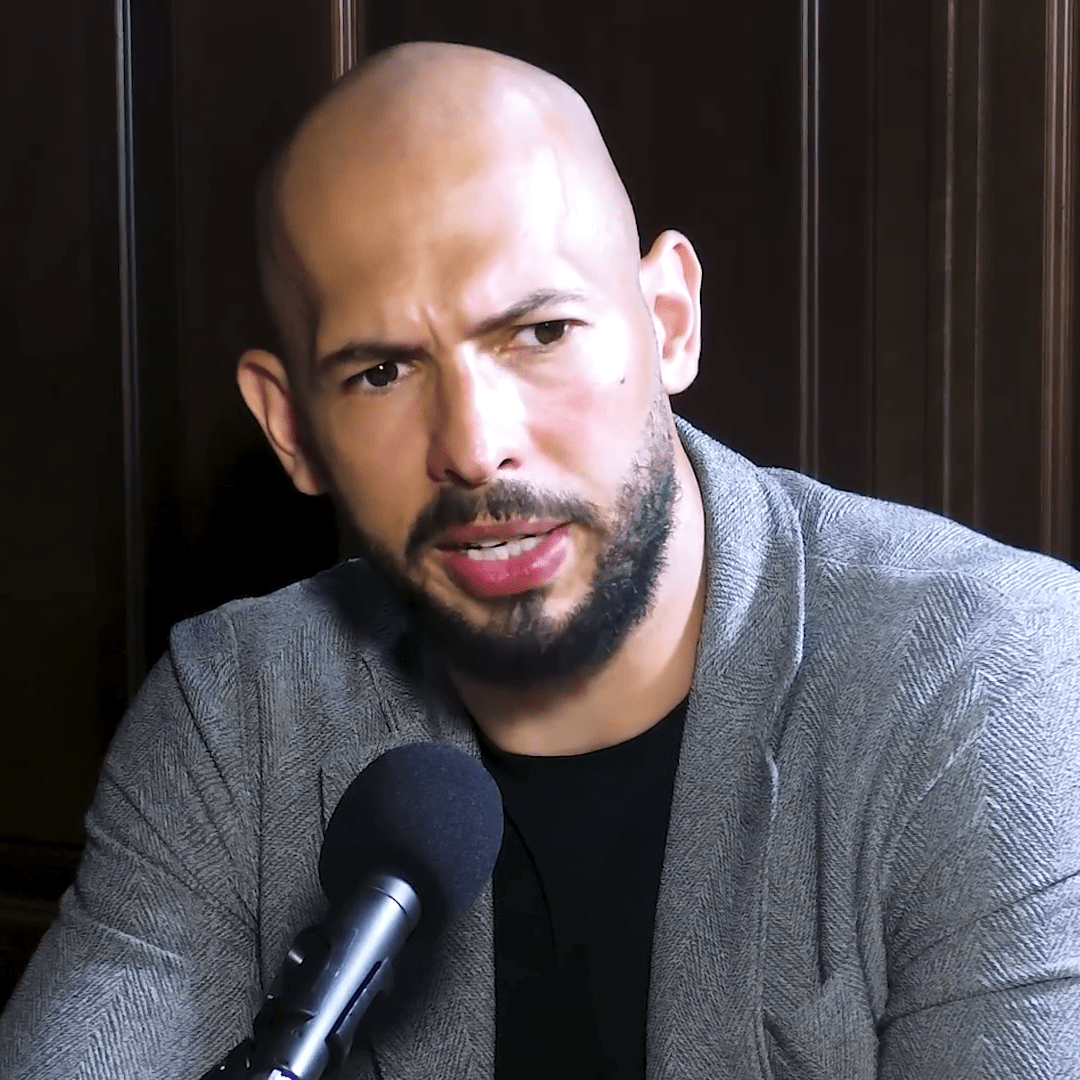

Despite facing charges for rape and human trafficking in Romania, the self-professed misogynist and social media masculinity influencer Andrew Tate (and his brother, Tristan) has arrived in the US after having his travel ban lifted.

We don’t know for sure, but there’s a suggestion that some form of pressure from Trump administration representatives has been at play in the decision of the Romanian authorities.

On the flip side, it now looks like Tate might also face a criminal probe in Florida.

What we can be more certain of is that there will be discussion of the overlaps between Trump’s policy positions and the views that Tate elevates and espouses. There’s an unmistakable alignment of their shared penchant for right-wing populism, anti-immigration outlooks, the revival of “strong man” masculinity hierarchies, and sensationalised digital culture warfare.

As this latest development unfolds, there will no doubt be talk of the way that figures of this network resonate in particular with disaffected young men. While this is certainly the case, we want to encourage us to step back to analyse the idea of who the disaffected are, and what our definition might cloud.

The economic disadvantage narrative

It’s become almost instinctive to assume that the young men drawn to Andrew Tate and the broader manosphere are primarily from working-class or economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

This narrative, often pushed by well-intentioned commentators, suggests economic hardship explains the appeal of these hyper-masculine spaces.

It also assumes that threats from gender equity and feminism are perceived exclusively by men within these communities, despite the power to resist social progress located among men of significant social and economic capital at the helm of large organisations or in government roles.

The Australian artist Tim Minchin, for example, has pointed to how financial struggle can leave young men vulnerable to promises of wealth and status offered by figures like Tate.

We have made this point ourselves, both in opinion pieces and in research that shows that economic issues can be gateways to more extremist manosphere content.

But while economic context plays a role, this explanation is incomplete and, frankly, risks misdirecting us away from the key endgame and the central “promise” of the manosphere.

Wealth and misogyny

First, let’s address the glaring contradiction – the persistent stream of news stories about boys from elite schools and prestigious universities engaging in misogynistic behaviour.

Recent cases from top private schools in Australia and the UK, and Ivy League higher education institutions in the US demonstrate that the attraction of manosphere messaging is not confined to those who aspire to economic mobility.

This is also clear in academic research showing that manosphere-inspired sexism is apparent in Australia’s elite private schools and state schools.

Read more: Post-truth politics and manosphere extremists in Australian schools

Wealthy young men, who already possess significant social capital, are just as susceptible. If the primary lure were financial, why would those already ensconced in privilege be drawn to it? Clearly, there’s something deeper at play.

Moreover, this narrative reduces the manosphere’s influence to a simplistic get-rich-quick scheme.

While Tate and his contemporaries do flaunt wealth as a signifier of success, the core underlying message is about gender dominance.

Tapping into entrenched beliefs

The manosphere is, at its heart, a revival and reinforcement of patriarchal power structures. It promises young men not just financial success, but a return to a world where male authority goes unchallenged – a world where women’s roles are subordinate and clearly defined.

This reassertion of gender power resonates across class lines, because it taps into entrenched societal beliefs about masculinity and control.

Interestingly, this economic hardship narrative comes from voices across the political spectrum. On the left, figures such as Tim Minchin and Owen Jones have discussed the allure of the manosphere in terms of economic disempowerment, framing it as a reaction to neoliberal failures and economic inequality.

Read more: Andrew Tate’s appeal to young men has nothing to do with toxic masculinity

While these perspectives highlight valid concerns about social mobility, they risk sidelining the central role of gender ideology. The manosphere’s appeal isn’t solely a response to material conditions; it’s also a powerful reaffirmation of traditional gender hierarchies.

On the right, commentators such as Piers Morgan and Jordan Peterson offer similar explanations, but from different ideological angles. Morgan has framed the issue as a response to male disempowerment in a tough job market, while Peterson often points to the lack of purpose among young men facing economic stagnation.

How such hostile economic conditions affect young women, or their reactions to such conditions, rarely, if ever, get a look in.

And anyway, despite their differing worldviews, these analyses converge on an economic rationale that overlooks how the manosphere strategically exploits gendered notions of power and dominance.

Promises of power resonate

This misunderstanding has serious consequences. By focusing predominantly on economic factors, we risk underestimating how deeply gender norms influence behaviour.

We also overlook how sexism and misogyny flourish in elite spaces where economic anxiety is minimal in relative terms.

The reality is that the manosphere’s promises of restored power resonate because they offer a clear, if toxic, script for reasserting male dominance in a world where traditional gender hierarchies are being challenged.

In tackling the influence of the manosphere, it’s essential to move beyond the narrative that it’s solely a product of economic hardship.

Yes, material conditions matter, but they are not the primary driver, per se. The manosphere’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to repackage old ideas about gender power in ways that feel new and rebellious, and in concert.

Influence of the ‘broligarchy’

It’s not without irony that these very feelings are stoked by very wealthy men who are in different ways complicit in, or take advantage of, growing economic hardship – the “broligarchy”, a collective of wealthy, powerful, right-wing men who exploit its networks of power and influence in aiding Trump's electoral win, including his appearance on Joe Rogan's podcast, and Elon Musk's monetary and public support.

But so, too, are many middle-class and/or moderately wealthy men who, emboldened by Tate and other manosphere figures, contribute to a resurgent and unapologetic sexism in contemporary times.

If we fail to recognise this, we risk leaving the core of the problem unaddressed – and leaving young men vulnerable to a seductive but ultimately harmful ideology that’s dangerous for women, girls, and gender-diverse people, and to boys and men themselves.

This focus on economic drivers of extremist sexism also works to make it justifiable, based on real or perceived challenges to stability and livelihood.

What this fails to recognise is that women and gender-diverse people harmed by manosphere ideologies are discarded as collateral in men’s struggle to survive in challenging economic landscapes – a precarity not exclusively experienced by men of any particular class background.

Shifting the narrative

Tate’s arrival on American shores will no doubt result in plenty of analysis. As disheartened as many of us are about any prospective lack of just process for Tate’s accusers, this moment also offers an opportunity to underscore that the revival of gender power and the sexism that ensues is led and perpetrated by elite, wealthy men who whip up disaffection to bring less-advantaged men with them.

It’s time to shift the narrative and confront this head-on – in schools, in workplaces, in policy discussions, and in the media.

We must stop excusing extremist sexism as an understandable response to hardship, and start recognising it as the calculated, well-funded backlash that it is. We cannot let the wealthier instigators off the hook and leave women, girls, and gender-diverse people exposed to real harm.