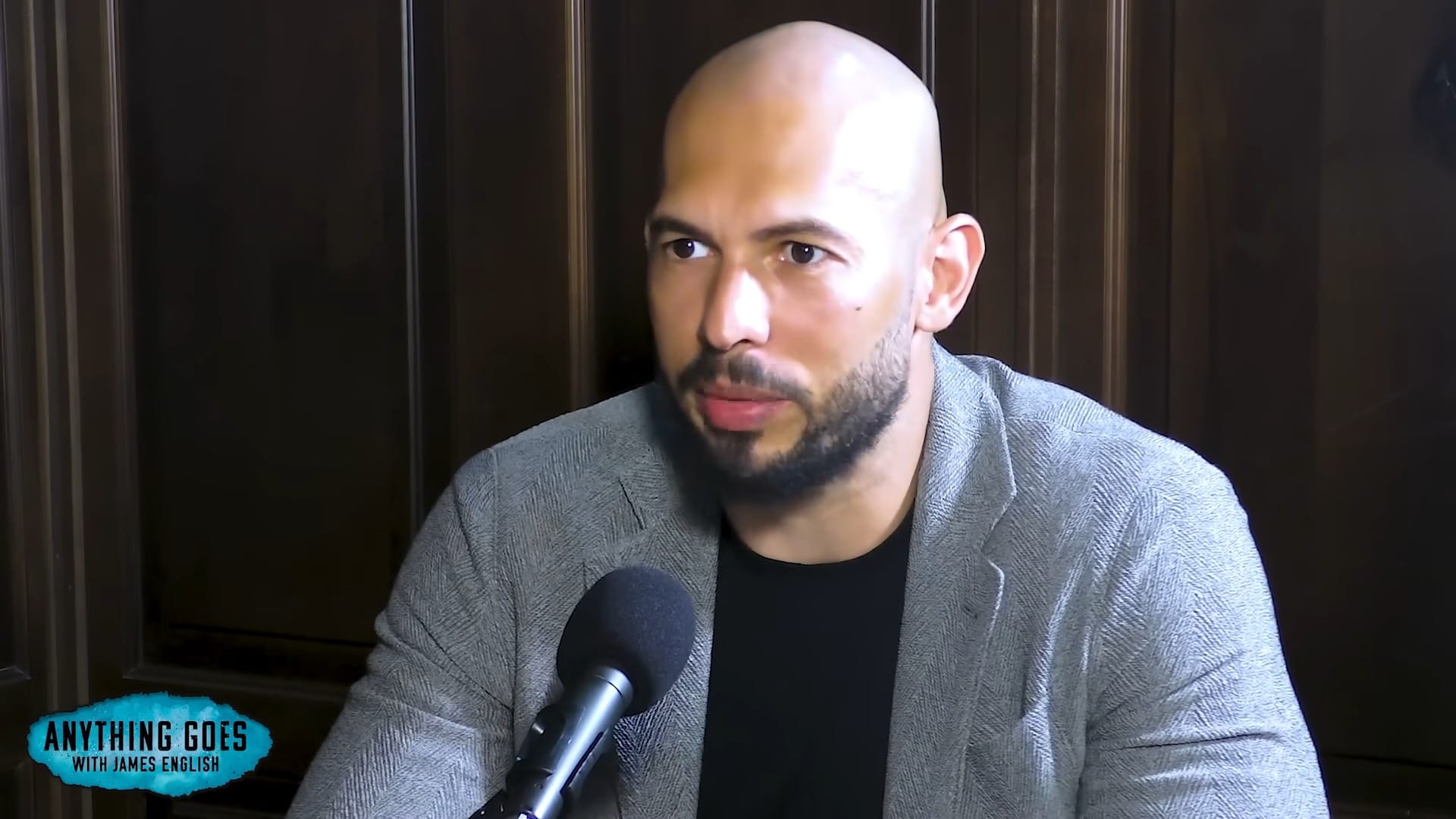

Commentary on the appeal of controversial figures such as Andrew Tate to boys and young men sometimes (and loudly) argues that these demographics are alienated by feminism, discussions of patriarchy, and use of the term “toxic masculinity”.

Some commentators suggest boys and young men are “tired of being blamed for a ‘patriarchy’ they had no part in creating”, and that this frustration drives them towards figures who appear to offer sympathy and an alternative narrative.

This explanation, however, confuses cause and effect. Regardless of whether we think the term “toxic masculinity” is helpful, the idea that boys and young men might gravitate to Tate because they hear talk of the phrase feels somewhat absurd.

To be blunter, it’s a wilful misrepresentation that puts cart before horse, and insists this nonsensical ordering is logical.

Rather than being a simple reaction to unfair societal accusations, Tate’s appeal lies in his skillful manipulation of genuine issues, such as economic hardships, and his ability to frame these issues as consequences of feminist efforts towards gender equality.

This frames women – and, in particular, feminists – as the enemy of men’s wellbeing and flourishing, which stokes an already growing ideological rupture. In doing so, Tate becomes not a reaction against patriarchy, but an embodiment of it.

Weaponising economic hardship

Andrew Tate and similar figures thrive by offering what appears to be a compelling solution to real economic struggles and political alienation faced by many young men across the world.

In an era of precarious employment, rising living costs, and growing inequality, many boys and young men find themselves facing uncertain futures. These issues are systemic in nature – rooted in neoliberal economic policies, structural inequality, and a global economy increasingly reliant on insecure labour.

Yet, rather than directing frustration toward these systemic causes, or making critiques of the political ideologies that enforce them, Tate weaponises economic anxiety, and redirects it toward feminism and advocates for gender equality. He frames women’s rights and the push for gender equity as scapegoats for broader societal problems.

This approach is incredibly dangerous. Tate’s narrative resonates with those who feel disillusioned and disempowered, and offers a simplistic, if deeply flawed, explanation: The world is unfair not because of complex economic forces, but because men have been “dethroned” by gender equality movements.

His rhetoric thus serves to reinforce patriarchal ideas by re-establishing traditional gender hierarchies as the solution to modern problems.

He tells boys and young men that reclaiming their “rightful place” atop the social order will restore stability and prosperity. In this way, Tate serves simply as the latest patriarchy-driven ideological entrepreneur, reshaping, defending and perpetuating its ideals for a new audience.

Misconceptions regarding ‘toxic masculinity’

In the public domain, an argument often made by critics of feminist discourse and advocacy is that terms such as “toxic masculinity” alienate boys and men, pushing them toward figures such as Tate.

This also assigns boys and men a victimhood status, whereby they claim to be persecuted by the use of a term that offends and mischaracterises them. This is separate from the considerable writing on the scholarly merits of the term as an academic concept.

This critique of a commonly-used lay term misunderstands the purpose and scope of the phrase. Toxic masculinity is typically taken by its critics as meaning – or at least conveying – that masculinity is harmful and bad.

We’re not committed to the term either way, but find it entirely non-controversial. Indeed, if understood in the way that the English language works, it’s pretty clear that it doesn’t label all masculinity as harmful.

Rather, the modifier “toxic” alludes to a specific set of behaviours and cultural norms that harm people of all genders – including boys and men themselves. These behaviours include aggression, emotional repression, and the pursuit of dominance at all costs, among other ideals that form a sort of “man box” that constrains boys and men.

By manipulatively framing the phrase “toxic masculinity” as an attack on men rather than a critique of harmful practices, figures like Tate exploit genuine feelings of alienation and defensiveness.

They present themselves as defenders of masculinity under siege, offering a space where boys and men can feel valued without having to confront or unlearn damaging behaviours.

This narrative, like the one around being blamed for patriarchy, is deliberately misleading. The issue is not that boys and men are unfairly blamed, but that they’re being offered false solutions by ideological entrepreneurs who profit from their discontent.

Ideological entrepreneurs in a post-truth era

The tactics employed by Andrew Tate can be understood through the lens of ideological entrepreneurship.

Ideological entrepreneurs are individuals who craft and promote specific ideologies for personal gain, often by exploiting societal anxieties. In Tate’s case, his brand of hyper-masculinity and anti-feminism taps into broader cultural insecurities and positions him as a thought leader for those seeking clarity in a confusing world.

This phenomenon is not unique to Tate. It mirrors the tactics of high-profile figures in the post-truth era, such as Elon Musk and Donald Trump. Both Musk and Trump are known for their ability to shape narratives that resonate emotionally, often at the expense of factual accuracy.

They create a sense of belonging among their followers, and make calls to broaden that following, by offering simple, seemingly compelling explanations for complex issues. In the same way, Tate offers boys and young men a narrative that makes sense of their struggles without requiring them to critically engage with the underlying causes.

The post-truth moment, characterised by the rejection of expert knowledge and the rise of emotional, subjective “truths”, creates fertile ground for ideological entrepreneurs.

Tate’s success is a symptom of this broader cultural shift. His followers are drawn not necessarily because his ideas withstand scrutiny, but because he provides a coherent, emotionally satisfying framework that appears to restore their sense of agency and control.

Challenging false narratives

Understanding the appeal of figures like Andrew Tate requires moving beyond surface-level explanations that blame feminist discourse for alienating boys and young men.

Instead, it’s crucial to recognise how these figures exploit genuine economic and social anxieties by offering regressive narratives that reinforce unequal gender power structures.

The challenge lies in addressing the real issues facing young men – economic precarity, social isolation, and the search for identity – without resorting to scapegoating or regressive ideologies.

Ultimately, combating the influence of ideological entrepreneurs requires fostering critical digital/media literacy, promoting nuanced discussions regardimng gender, and creating spaces where boys and young men can explore healthy forms of masculinity.

Only by addressing the root causes of their discontent can we hope to counter the appeal of figures like Andrew Tate, and build a more equitable society for all genders.