With yet another sexual harassment imbroglio in the corporate world, and the university sector now witnessing the same embarrassing failure, surely we’ve all come to recognise that the exploitation of power is not simply an aberration.

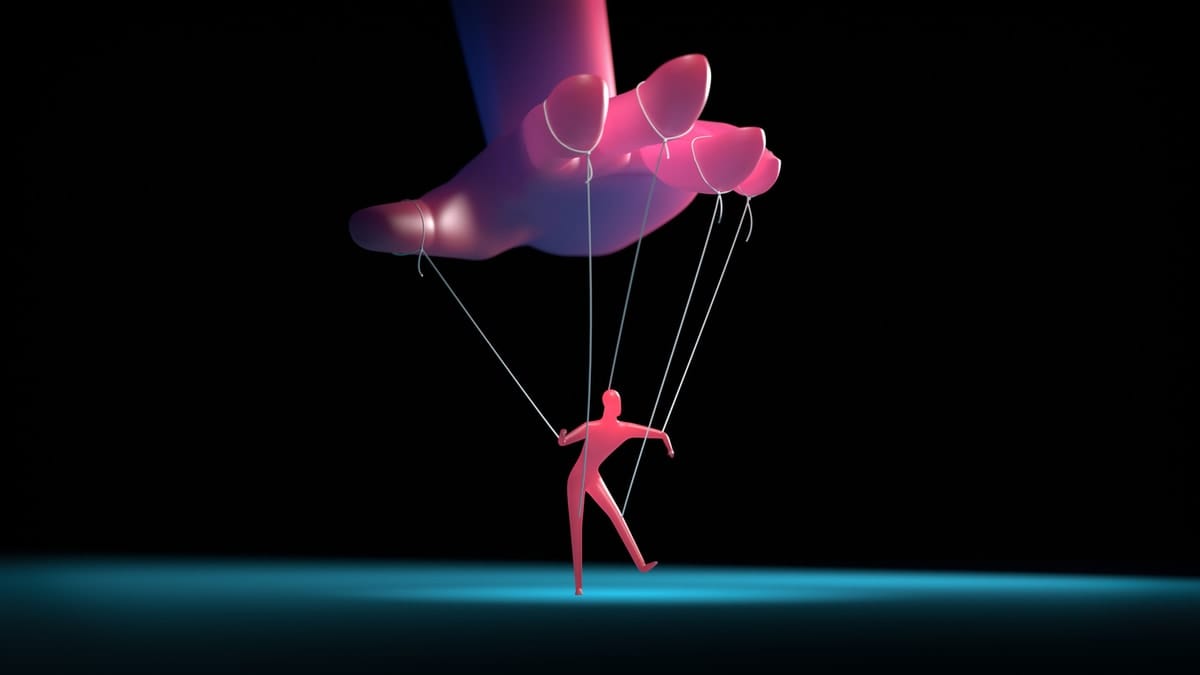

Focusing on the particulars of sexual harassment, and the outrage it rightly generates, can easily draw our attention from everyday asymmetries of power in so many of our institutions that that make these transgressions not only possible, but likely inevitable.

In my research in elite private boys’ schools, these asymmetries of power were crucial mechanisms by which sexual harassment was enabled. Like employees in the corporate world, the female teachers in the study who experienced sexual harassment were also understandably fearful of being blamed for their invidious circumstance, because disbelief and denial was commonly experienced when these teachers spoke up.

The evidence suggests that sexual harassment occurs in part because schools are run like private enterprises, and generate the very same asymmetries of power in relationships between employers and employees, but also between high-fee-paying clients and staff, that we see in so many other private sectors.

The tensions within gendered relations certainly intersects these broader relations of power, but it is power that we need to understand. Not only do we need to understand how power functions in workplaces, but also understand that highly asymmetric labour relations are the norm and not the exception.

Vulnerable workers have little choice in accepting their lot, but this comes at a price for us, too. Teachers in elite private schools may be a little more empowered when compared to workers in the gig economy, but the benefits and conditions of their work rest on their willingness to not rock the boat.

When issues like sexual harassment emerge, it’s hardly surprising they’re erased rather than addressed, because reputational damage is a central concern of any market-facing organisation. And modern elite private boys’ schools that charge high fees for the prestige they offer are certainly in that category. If employees fear their employers as much as they might dread their KPIs, or perhaps more so because our employers almost always “hold the keys to your future”, then those keys are also the keys to our shackles.

Dropping the profit-driven agenda

What’s to be done? I would argue that thinking about “What if?” might bring us from where we’re at, to where we want to be.

What if our economy privileged inclusiveness, community and wellbeing instead of an endless profit-driven agenda? Sure, profit is a great motivator, but what if we instead valorise the nurses, firemen, soldiers, paramedics, teachers, cleaners, drivers and the endless list of our fellow citizens who make society work for us, who do so without ever yearning for the excesses of corporate success.

What if schools were treated as educational opportunities rather than commodities to be bought as a competitive advantage? What if we didn’t double down on the need to eviscerate labour protections and instead start working for a fairer system that worked for everybody, not just the few.

What if a fair system was actually possible, one that included a radical urge towards levelling the dramatic power discrepancies in our institutions?

What if …?