Recent media coverage has revealed some of Victoria’s wealthiest private schools are reporting spikes in the numbers of students with disabilities.

Many (but not all) wealthy private schools schools were initially identified as overfunded, and were set to lose government funding to bring them into line with the Schooling Resource Standard (SRS). This makes it surprising that schools earmarked to lose funding now appear set to increase their funding through top-ups for disadvantage.

Reportage needs to be moderated to ensure these schools aren’t “gaming the system” at the expense of public school students.

Why would the numbers of students with disability change?

Some change was expected following the amendments to the Australian Education Act (2013), known as Gonski 2.0. These amendments ushered in a new model for disability funding by providing top-ups to the SRS in the form of “needs-based funding” for educational disadvantages, such as disability. It was announced that this model would use the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data for Students with Disability (NCCD) to replace previous methods for identifying and funding students with a disability.

Prior to Gonski 2.0, only those who received funding were counted, which was problematic for a number of reasons. One reason was that it involved students with disability and their families going through complex, lengthy, and potentially expensive assessments before it could be determined if a student would qualify for funding. This disadvantaged some and led to others being misdiagnosed in order to receive school funding support. Another reason was that it was deficit-oriented. Students were only eligible for funding if they failed psychological and similar tests. A further issue with this model was that it underestimated the number of students with disability, as it did not count students without funding.

So, while an increase in the numbers of students under the new model is unsurprising, an “alarming” increase in funding raises questions.

What is the new model?

The NCCD includes both a counting process and a funding formula based on an annual census. The NCCD is based on the idea that teachers are better positioned to identify which students need an adjustment relating to a disability. Teachers then determine the type and level of adjustments in teaching and learning, where this was previously done by professionals distant from the realities of the classroom. The NCCD empowers teachers to make important decisions about which students need adjustments, and the type and level of adjustment needed to provide high quality education to the students in their classroom. The student numbers, disability types, and levels of adjustment are then reported in an annual census.

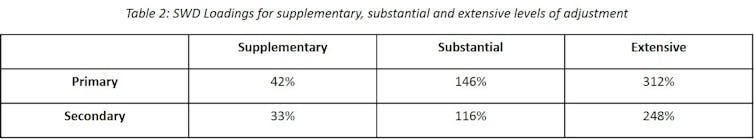

Adjustments are judged based on four levels of support: Quality Differentiated Teaching Practice (QDTP), Supplementary, Substantial and Extensive. The latter three attract a scaled financial loading that is then tallied and granted as needs-based funding to schools to fund the provision of these adjustments. Ideally, schools should ensure that funds are used in providing adjustments that are supported by research evidence.

Table notes: 2018 loadings for levels of NCCD adjustment. Australian Government Department of Education and Training Submission to Select Committee on Australian Education Amendment Bill

NCCD is robust, but overestimation can occur

Schools are legally obliged to provide adjustments, and the census provides accountability under the legislation. With the recent connection of the NCCD to a funding model, the stakes are further increased.

In light of the perceived manipulation by wealthy schools, it is important to consider that the PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) report on the quality of this model has suggested it is robust, with relative stability on the numbers of students needing support at each level throughout Australia.

However, they identified some schools that overestimated the level of support. Such overestimation could potentially explain unexpected rises in funding for those schools reporting increased numbers of students with disability needing supplementary, substantial or extensive support.

Trained staff and moderation key to getting the numbers right

Two issues are key to enhance trust in the numbers reported and data quality.

One is training. Staff should be trained in the key legislation, such as completing the online training in Disability Discrimination Act and Education Standards http://dse.theeducationinstitute.edu.au/login/index.php. The should also undertake training in the NCCD processes and engage in professional learning through working with the resources provided for this purpose.

The other is to ensure that schools engage in moderation. This would mean two or more teachers independently judging student needs and level of adjustment, and then comparing and reaching agreement using evidence. Schools can use the moderation resource produced by our team to ensure reliable reporting of the students and the levels of adjustment. By using the process outlined in this resource, schools should be in a position to defend their numbers and funding requests. Schools should also be able to produce evidence in support of their decisions.

Extending the moderation process between sectors and states can further improve the reliability of the data and the public’s confidence in the new funding model.

Schools should be able to justify their claims

An increase in numbers and funding is justifiable, providing schools can demonstrate they are not artificially increasing the level of adjustments, have qualified staff responsible for compiling NCCD data, and have engaged in moderation process. Only under these circumstances should the public trust the numbers.

This article first appeared on The Conversation

Umesh Sharma received funding from the Department of Education and Training to develop the School Moderation Resource for NCCD. Umesh is a Member of the Australian Psychological Society and the American Psychological Association.