Whether sleeping on a rock, surfing down a wave, or snapping at a penguin, seals and sea lions are a key part of our modern oceans.

These charismatic creatures are somewhat unusual, as air-breathing mammals that sleep and breed on land, but venture into the ocean in pursuit of food. But it's impossible to imagine our coastline without them – in many places the beach rocks are literally worn smooth by the countless generations that have come ashore to rest.

Yet the species that sun themselves today are not necessarily the same as those who visited in past millennia. Long ago there were other seals, species whose existence is only known from the fossils buried in these rocks. And today, the count of ancient seals has gone up, as we describe two new species discovered at the far ends of our planet, rewriting our understanding of what ancient seals were like, and where they evolved.

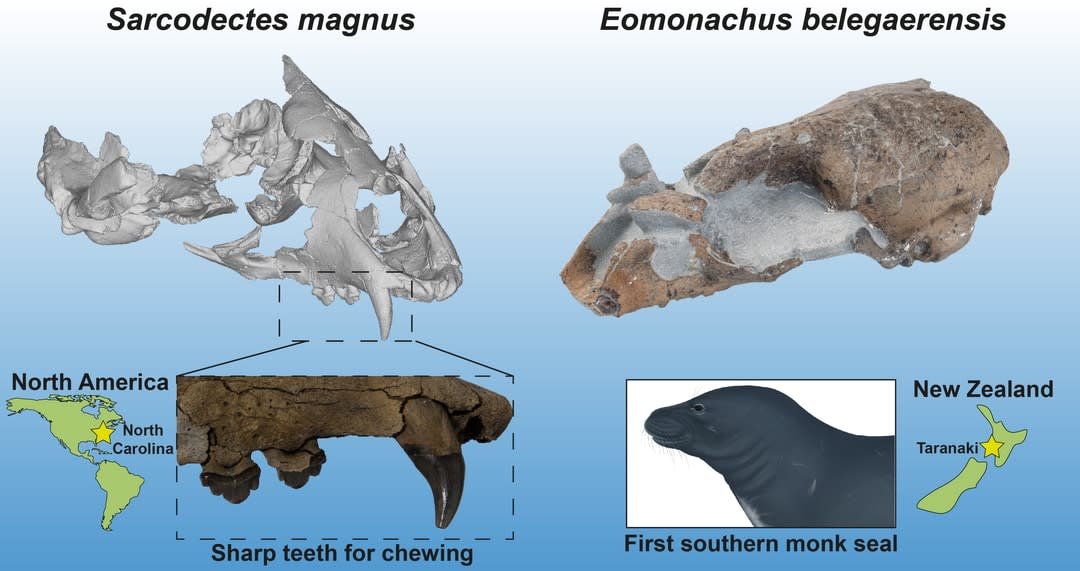

The first of these, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, is a large fossil seal with sharp bladed teeth, giving it the Latin name Sacrcodectes magnus, which means “large flesh biter”. Today’s seals, in contrast, mostly have simple pointed teeth that are good for snapping up fast-swimming fish, but Sarcodectes’ teeth seem better-suited to chewing up large prey.

This style of feeding is more similar to how land-dwelling carnivores eat, and so helps us to understand the changes that seals went through over time as they evolved from an otter-like semi-aquatic animal through to the agile aquatic hunters that dwell in modern oceans.

Sarcodectes, whose fossilised remains are housed in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC in the United States, lived on the east side of North America about 4.5 million years ago, a coastline that is today home to only the smaller harbour and grey seals.

Based on the size of its skull, we think Sarcodectes would have been around 2.8 metres long, making it one of the largest fossil seal species to be discovered. But this is still small compared to the true giants of the seal world – the living southern elephant seals, which can reach up to five metres long and weigh in at 4000kg.

Read more: Rare fossil tooth discovery reveals extinct group of seals from Australia’s deep past

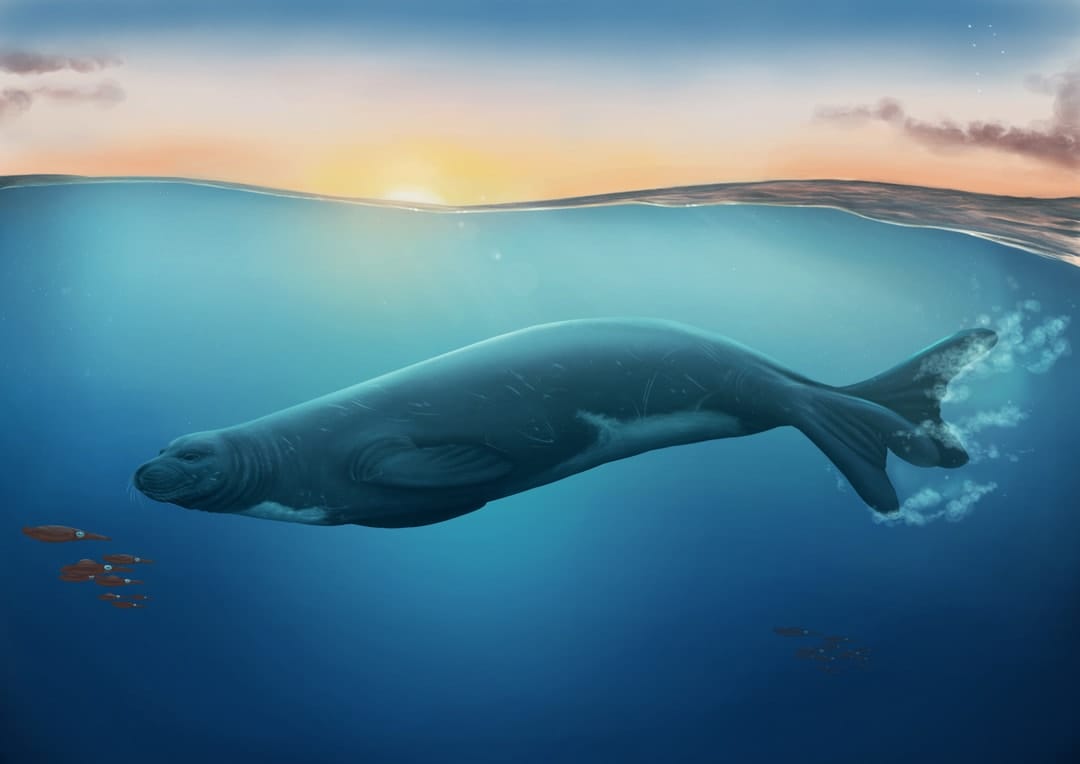

It is here, in the southern hemisphere, that our second newly discovered seal once lived, swimming along the shorelines of New Zealand about three million years ago. Today, this part of the world is home to fur seals and sea lions. These are the fast-swimming seals known for their wing-like flippers and dog-like barks.

However, when we examined fossils from the Taranaki coastline, on New Zealand’s North Island, we were shocked to discover the world’s first southern monk seals.

Today’s surviving monk seals are sun-loving tropical species, living in the warm waters of the Mediterranean and Hawaiian islands. Discovering monk seals in New Zealand therefore came as a surprise, because it writes a very different picture for how the southern hemisphere’s seals evolved long ago.

Read more: Deep impact: grey seals clap underwater to communicate

Rather than first appearing in the North Atlantic before moving south, these new fossils indicate that the southern seals originated “down under”, and for that reason we have named this seal Eomonachus belegaerensis – the dawn monk seal from Belegaer (the western “Great Sea” from Tolkein’s Middle Earth, whose unofficial home is also in New Zealand). This species is also first published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society.

The discovery of these new species helps to paint a clearer picture of what life was like in the ancient oceans. However, it also highlights the changing fates that can allow some species to thrive, while others are lost to the mists of time.

Sarcodectes and Eomonachus both disappeared at a time of climatic turmoil, as shifting sea levels led to habitat changes that may have made it difficult for these seals to find food and safe beaches to rest and breed.

In a worrying parallel, today’s surviving monk seals remain some of the world’s most endangered marine mammals, at grave risk of extinction from changes in their environment due to human activities and the ongoing threat posed by climate change.

So perhaps these discoveries can also act as a warning, reminding us of what can be lost from the world forever, while we still have time to act.