Rewind to October 2020, and both Melbourne and the wider state of Victoria are getting towards the end of two gruelling pandemic lockdowns. There would be five more (including in the regions) of varying lengths and restrictions to come. What does this mean for older people who already say they are lonely?

October that year was when 32 Victorians aged 65 or older, who had previously told Monash University social scientists about loneliness, were given diaries to document how they managed a week in lockdown.

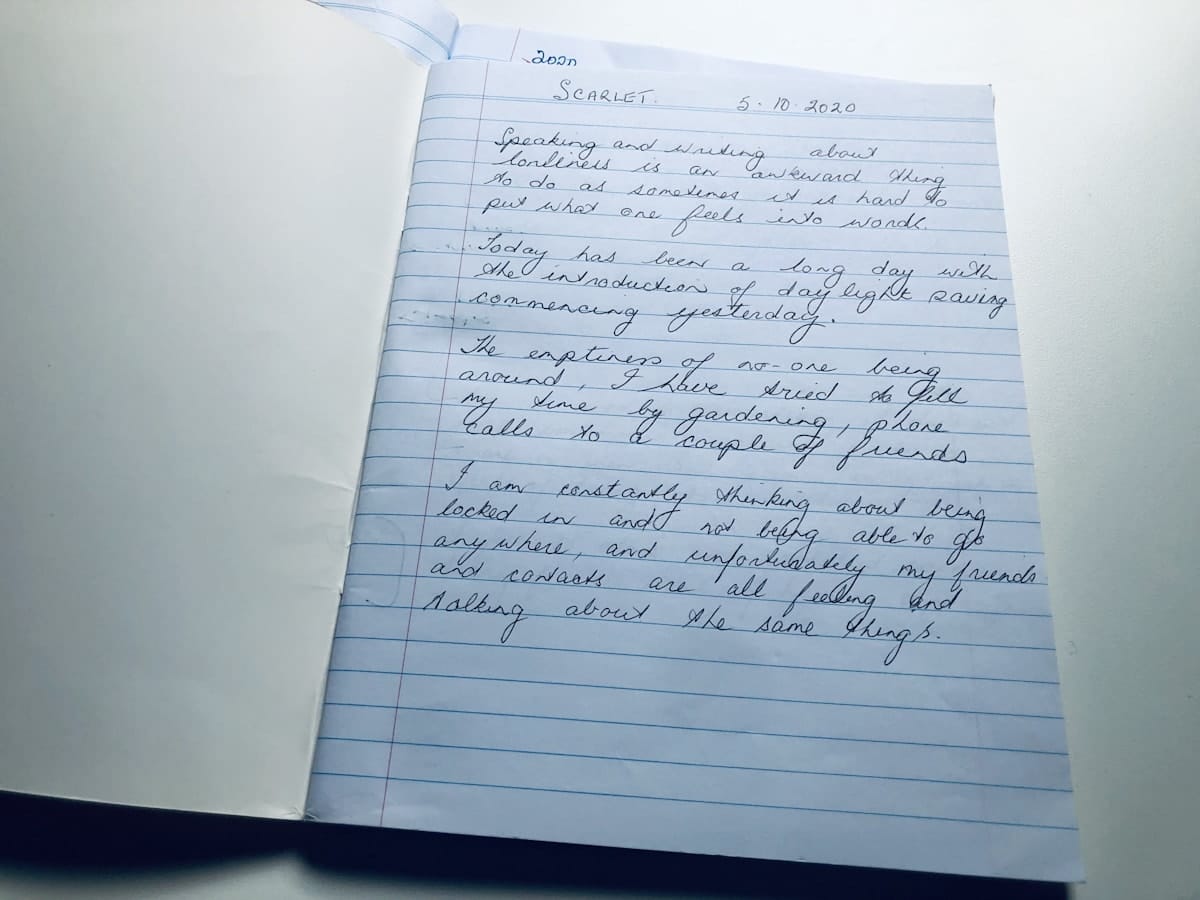

Nineteen of the participants hand-wrote their entries in a supplied journal, while 13 chose digital means (email, text documents or audio). Six lived in regional Victoria, the rest in Melbourne. Lengths of individual diaries ranged from 500 words to almost 8000 words.

At the time, regional Victorians were under stage three restrictions, while Melbourne languished under stage four, which included a curfew between 8pm and 5am, a 5km travel radius, and a two-person limit on “gatherings”.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that diaries have been used to study loneliness in later life,” says Dr Barbara Barbosa Neves, of the School of Social Sciences in the Faculty of Arts.

“Loneliness is a very sensitive issue, and it’s associated with a lot of stigma. Most of our participants associate it with a personal failure, with something that’s negative about them. Maybe they're not interesting enough, maybe they’re not friendly enough. They see it as a personal failing in a sense.

“When there's stigma, it's even harder to talk about, but the diaries gave our participants a possibility of talking about loneliness in a way they could control.”

Participants as equals, not subjects

The diaries also helped in positioning participants as equals, or research partners, rather than research subjects.

“We wanted them to feel equal, but we also wanted them to feel that they had the right space and environment to talk about really negative things with us. A lot of the diaries covered their thoughts about suicide, for example. This was possible because we created a safe space for participants.”

The writers were given 10 prompts and asked to make entries twice a day, but were also told they could ignore the prompts and just write about whatever they were feeling. One such prompt was “What was it like living alone today?”; another was “What have I done today? What do I feel about it?”

“Sociologically speaking, when people write diaries or journals, they tend to reflect on their immediate moment and context, what they're feeling now, and why, which also allows us to make sense of our feelings and circumstances,” says Dr Neves.

Painting a bigger picture

The result was a fuller picture than might have been anticipated by the group of Monash researchers.

“They engaged with their life stories, their biographies, their experiences from the past, which provided us with a more complete understanding of their life circumstances,” says Dr Neves. “Many talked about their past compared to their present, when they feel ‘old and frail’.

The results, published in The Gerontologist, defined loneliness in this context as a “detrimental absence of companionship and meaningful social interactions”.

Dr Neves, the paper’s lead author, says some of the longest and strictest lockdowns in the world exacerbated existing loneliness, presented new triggers, and upended older people’s usual coping strategies, leading to emotional suffering, suicidal thoughts, and the feeling of being rejected by society during the pandemic.

Several participants struggled to put their finger on the feelings they were experiencing.

“Scientifically, we tend to try to categorise everything,” Dr Neves says. “We often state that loneliness is a subjective feeling of lacking companionship and missing meaningful relationships, but we could see that it's much more than that.

“It's very complex, because it intertwines with other elements in their lives, with the stigma of being old, and the stigma of being frail in a society that devalues both. We know that in our society, being old is something that’s not seen in a positive light, and being frail is not seen positively either – reflecting ageism and ableism.

Read more: How storytelling is helping us better understand ageing and loneliness

“Many participants talked about how they feel like unproductive parasites in a society so obsessed with productivity. They all mentioned that loneliness is a negative feeling, that it’s about suffering, a pain, an emotional pain.

“Diary entries mentioned frequent crying, distress, sadness and anguish, with many reporting feeling devalued, unimportant and purposeless.

“Close relationships were affected, and previous coping mechanisms such as volunteering or going on outings were discontinued, interrupting their social lives and making activities such as shopping for essentials of importance, as they provided socialisation opportunities.”

A difficult read

Many of the diary entries are confronting to read. Names were changed. Participants chose their own pseudonyms.

“June” wrote: “I tell everyone I love being on my own, but in fact I hate it.”

“Colin” asked: “What purpose is there to exist?”

“Fred” described the two ends of the day. “Morning: Yet again, I swing my legs out of the bed with a certain amount of apprehension. What will the day bring? Whatever it brings, I will face it alone. Bedtime: One of the most difficult times of the day.”

Read more: Un-neighbourly? Fear of crime among older people points to social isolation

Dr Neves explains that because the study participants had already told researchers they were “lonely” before the pandemic, the coping strategies they had in place pre-COVID went out the window.

“They couldn't rely on the things that they had put in place before, such as going for walks with friends, or doing volunteering work, or attending events at social clubs.

“A lot of those strategies were completely interrupted, so they had to rethink and reconfigure them. This is really important, because frail older people are often seen as passive, which is wrong, because they routinely engage in considerable efforts to try to cope with their own issues, including loneliness.

“It doesn't mean that they’re always successful. Many strategies put in place are just to distract themselves from their loneliness.”

She says this is because generally a lonely older person doesn’t want to talk about it.

“They don't want their families to see them as lonely old people. They already feel so stigmatised, and this is another layer of stigma.

“Also, they want to retain or hold onto their status as independent older people. A lot of them said they didn't want to go to a ‘nursing home’, and so they must show others that they are very capable of living on their own.”

An emotional burden

Feeling lonely is an emotional load on older people, the social scientists say.

“It's a social issue that is so individualised that people assimilate and internalise responsibility for their loneliness,” Dr Neves says. “In our Western societies, individuality and self-reliance are so highly praised that we tend to forget the importance of community and caring for each other.

“What sociologists have been trying to say for a long time is that loneliness is not only a personal issue, it’s also a social issue. It relates to our social relationships, our social opportunities, our social communities, the way that we see each other in society.”