Alex Vo is 21. He’s a Monash pharmacy student in his fourth year – and, suddenly, also a key foot-soldier in Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

He works hard for intense two-hour periods, takes a break, and works some more, preparing vaccines for injection. The attention to detail and fine precision in his role means he requires those frequent breaks. He works with the vaccine vials as if they’re precious gems – which, in a way, they are.

His job – while on fourth-year placement at The Royal Melbourne Hospital – is preparing AstraZeneca vaccines so that health workers at the hospital can be protected. He works in a pop-up preparation room repurposed from the former hospital library, beside a team of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

State government regulations – only amended in February – mean that fourth-year pharmacy students can now do this sort of high-stakes work.

Down a corridor and around a few corners, the Pfizer vaccines are also being prepared. The pharmacy students – Alex is one of a team of 16 – are trained to prepare these as well, but it’s an even more complicated, exacting process.

The required Commonwealth, state, and hospital training was extensive, including both online and practical elements.

The opportunity for Alex and his student colleagues (on placement and also employed as part of the hospital’s “surge workforce”) is immense.

“It’s once in a lifetime, possibly,” he says. “How many times will I be actively involved in a pandemic like this? I know I’m responsible for helping others get vaccinated. I’m hands-on.”

Read more: From Baghdad to Melbourne: Dr Harry Al-Wassiti's remarkable journey

The Monash students don’t do the actual vaccinating the way they can in some parts of Australia.

Monash postgraduate pharmacy student Ethan Kreutzer is the president of the National Australian Pharmacy Students’ Association (NAPSA), and has been lobbying the Victorian, South Australian and Northern Territory governments to allow students to administer the vaccines.

Call for a broader change

Professor Tina Brock, from Monash’s Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, says trained pharmacy students from all year levels from one pharmacy school in Colorado in the US have administered 33,000 vaccines in 13 weeks. “I’m proud of what our students are doing,” she says, “but I also want to keep the pressure on for broader change.”

Instead, they prepare the vaccines, which is an exercise in itself. Watching this preparation is like watching choreography – it can look almost like tai chi movements.

“It’s once in a lifetime, possibly. How many times will I be actively involved in a pandemic like this? I know I’m responsible for helping others get vaccinated. I’m hands-on.”

The Pfizer vaccine arrives at the hospital in a multi-use vial that’s been thawed previously at another hospital. The vial is “inverted” gently, which means the student preparing it must wave it in a slow arc through the air in front of them, upside-down and right-side-up, 10 times.

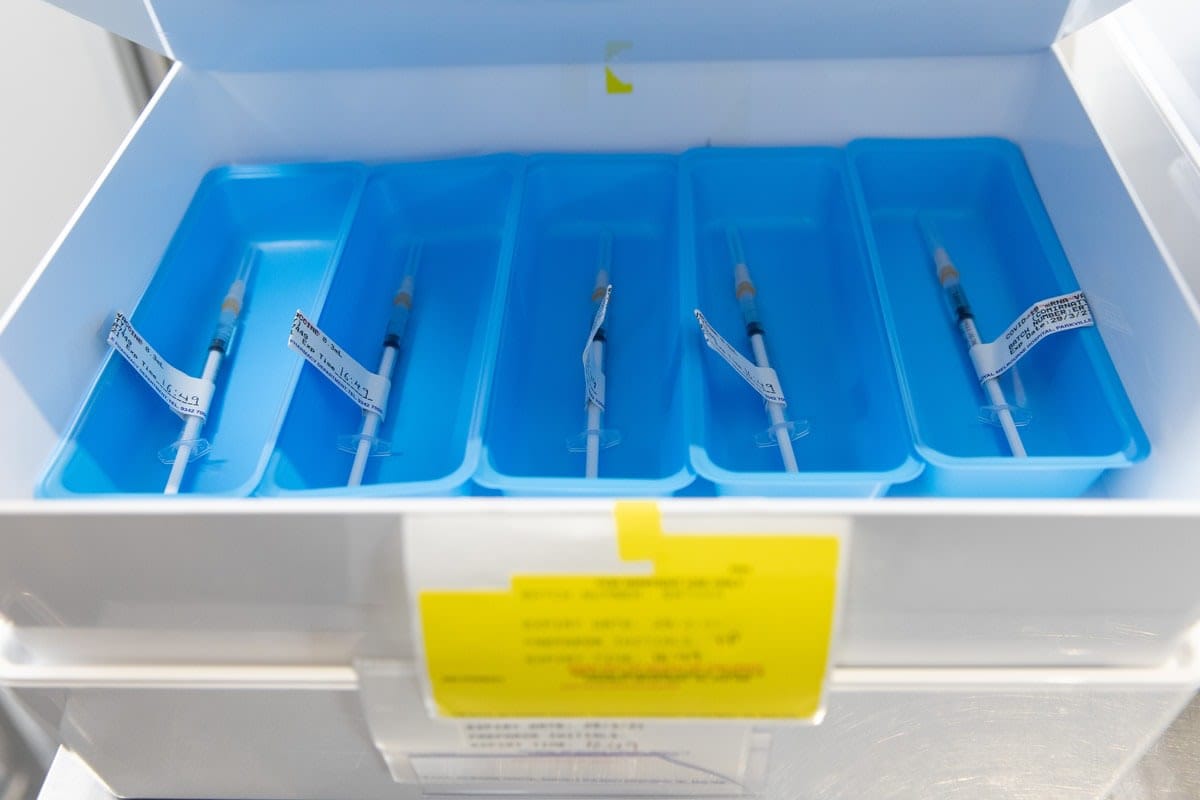

Then a specific amount of liquid saline is added, and the same amount of air is withdrawn. This keeps the pressure in the vial in step with the pressure outside the vial, so there are no leaks. Then the student begins another series of 10 more gentle inversions of the diluted vial. Only then is exactly 0.3ml ready to be drawn into the syringes for administration.

This rhythmic process is carried out in a temporary pharmacy behind glass partitions in full view of those waiting to be vaccinated.

This “transparency” is important, says Professor Brock.

“It was a brilliant move by The Royal Melbourne’s pharmacy department to say, ‘If you’re worried, we invite you to watch us do this,’” she says. “‘We’ll show you it’s safe and secure. We’re not behind closed doors. We’re showing you that being vaccinated is the right step to take.’”

Despite major logistical, commercial and public health issues with Australia’s vaccine rollout, the work at The Royal Melbourne Hospital and many other of Victoria’s vaccination hubs continues. As of April 15, 155,928 Victorians have been vaccinated with the required two doses from hospital hubs.

The AstraZeneca issue

The main problem through April has been with the AstraZeneca vaccine, which is by far the most widely available. The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) told the federal government the Pfizer vaccine is preferred for people under 50 because of the risk of a rare but serious side effect related to blood clotting with the AstraZeneca product.

Some of the country’s original 10 million Pfizer doses have been used already in the first phase of the rollout – aged care, frontline healthcare workers, and hotel quarantine staff. The government has bought 20 million more doses, but they aren’t expected to be ready until at least October.

The AstraZeneca vaccine, meanwhile, while originally imported, is now being made by the pharmaceutical company CSL in Melbourne. Other vaccines may be available in Australia later in the year.

The Royal Melbourne Hospital also manages the vaccination hub at the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre. This site also prepares vaccine doses behind transparent glass.

“The partnership between The Royal Melbourne Hospital and the pharmacy faculty at Monash University is an important element of the rollout of a successful vaccination program,” says the hospital’s Director of Pharmacy, Paul Toner, who’s overseen the pharmacy students’ integration into the vaccine workforce. “The situation is changing regularly, but it’s business as usual for us.”

Read more: In their own words: Work placements put students on the COVID-19 frontline

The Monash students have plenty to do, every day. Shifts start early. The level of detail required in the work is astounding, from careful storage, shredding packaging to avoid the potential for counterfeiting, and then, of course, the extraction of the liquid gold into syringes, being careful of waste and accounting for every drop.

“I wouldn’t have wished for a global pandemic to be the stimulus for change,” says Professor Brock, “but when we have innovative partners like The Royal Melbourne Hospital’s pharmacy department inviting our students in to help, it shows that they can contribute to public health.

“How much more real-world can you get?” she asks, looking through the glass to the students at work. “The classroom is interesting, but this is real.”

Tina Brock was Professor, Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Director of Pharmacy Education, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at Monash University at the time of writing this article.