Climate shocks threaten to devastate communities, overwhelm emergency services and strain health, housing, food and energy systems, according to a federal government assessment released today.

The report, Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment, confirms the devastating consequences of climate change have arrived. It also reveals the worsening effects of extreme heat, fires, floods, droughts, marine heatwaves and coastal inundation in coming decades.

The sobering assessment is a major step forward in Australia’s understanding of who and what is in harm’s way from climate change. It’s also a national call to action. The sooner Australia mitigates and adapts, the safer and more resilient we will be.

Australia’s climate risk revealed

The assessment involved more than 250 climate experts, including the authors of this article, and contributions from more than 2000 specialists. It was also informed by data and modelling from the Australian Climate Service, CSIRO, Bureau of Meteorology, the Australia Bureau of Statistics and Geosciences Australia, among other major institutions.

The report provides the vital evidence base to inform Australia’s first National Adaptation Plan, also released today.

Earth has already warmed by 1.2°C since pre-industrial times, and remains on track for 2.7°C by the end of the century if no action is taken. The assessment considers the impacts on Australia at 1.5°C, 2°C and 3°C of global warming.

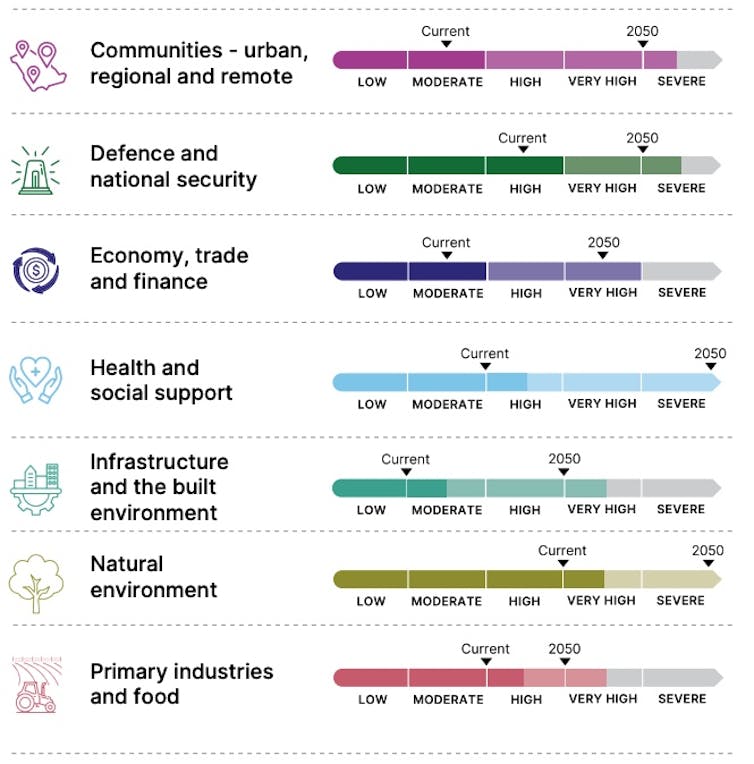

The risks to Australia are assessed under eight key systems, as we outline below.

1. Health and social support

Climate hazards will severely impact physical and mental health. The most vulnerable communities include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the elderly, the very young and those with pre-existing health conditions, as well as outdoor workers.

At 3°C global warming, heat-related deaths increase by 444% for Sydney and 423% for Darwin, compared with current conditions.

Deaths from increased disease transmission are expected to rise. Vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever may spread in the tropics.

Attracting healthcare workers to remote areas will be increasingly hard, and services will be strained by rising demand and disrupted supply chains.

2. Communities

Coastal, regional and remote communities face very high to severe risk.

More than 1.5 million people in coastal communities could be exposed to sea level rise by 2050, increasing to more than three million people by 2090.

Communities within 10km of soft shorelines will be especially vulnerable to erosion, inundation and infrastructure damage.

Extreme weather events – including heatwaves, bushfires, flooding and tropical cyclones – will intensify safety and security risks, especially in Northern Australia.

Compounding hazards are expected to erode community resilience and social cohesion. Water supplies in many areas will be threatened. Economic costs will escalate and people may be forced to migrate away from some areas.

3. Defence and national security

Climate risk to defence and national security is expected to be very high to severe by 2050. This system includes emergency management and volunteers.

Defence, emergency and security services will be increasingly stretched when hazards occur concurrently or consecutively.

If the Australian Defence Force continues to be asked to respond to domestic disasters, it will detract from its primary objective of defending Australia. At the same time, climate impacts will cause instability in our region and beyond.

Repeated disasters and social disruptions are likely to erode volunteer capacity. Increasing demands on emergency management personnel and volunteers will intensify, and may affect their physical and mental wellbeing.

4. Economy and finance

Risks to the economy, trade and finance is expected to be very high by 2050. Projected disaster costs at 1.5°C could total A$40.3 billion every year by 2050.

Losses in labour productivity due to climate and weather extremes could reduce economic output by up to $423 billion by 2063. Between 700,000 and 2.7 million working days would be lost to heatwaves each year by 2061.

Extreme weather will lead to property damage and loss of homes, particularly in coastal areas. Losses on property values are estimated to reach A$611 billion by 2050. Insurance may become unaffordable in exposed areas, putting many financially vulnerable people at further risk.

Coupled with increased prices for essential goods, living costs will rise, straining household budgets.

The economy could experience financial shocks, leading to broader economic impacts that especially affect disadvantaged communities.

5. Natural environment

Risk to the natural environment is expected to be severe by 2050.

Important ecosystems and species will be lost by the middle of the century. At 3°C warming, species will be forced to move, adapt to the new conditions or die out. Some 40% to 70% of native plant species are at risk.

Ocean heatwaves and rising acidity, as well as changes to ocean currents, will massively alter the marine ecosystems around Australia and Antarctica. Coral bleaching in the east and west will occur more frequently and recovery will take longer.

Ocean warming and acidification also degrades macroalgae forests (for example, kelp) and seagrasses. Freshwater ecosystems will be further strained by rainfall changes and more frequent droughts.

Loss of biodiversity will threaten food security, cultural values and public health. The changes will disrupt the cultural practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their connection to Country.

6. Infrastructure and the built environment

By 2050, the climate risk to infrastructure and built environment is expected to be high or very high.

Climate risks will push some infrastructure beyond its engineering limits, causing disruption, damage and, in some cases, destruction. This will interrupt businesses and households across multiple states.

Extreme heat and fires, as well as storms and winds, will increasingly threaten energy infrastructure, potentially causing severe and prolonged disruptions.

Transport and supply chains will be hit. Water infrastructure will be threatened by both drought and extreme rainfall. Telecommunications infrastructure will remain at high risk, particularly in coastal areas.

The number of houses at high risk may double by 2100. Modelling of extreme wind shows increasing housing stock loss in coastal and hinterland regions, particularly in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

7. Primary industries and food systems

By 2050, risks to the primary industries and food systems will be high to very high. This increases food security risks nationwide.

Variable rainfall and extreme heat will challenge agriculture, reducing soil moisture and crop yields. Farming communities will face water security threats.

Hotter climates and increased fire-weather risks threaten forestry operations. Fisheries and aquaculture are likely to decline in productivity due to increased marine temperatures, ocean acidity and storm activity.

The livestock sector will face increased heat stress across a greater area. At 3ºC warming, more than 61% of Australia will experience at least 150 days a year above the heat-stress threshold for European beef cattle.

Biosecurity pressures will increase. Rainfall changes and hotter temperatures are expected to help spread of pests and diseases.

8. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

As part of the assessment, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples identified seven additional nationally significant climate risks:

- Self-determination

- Land, sea and Country

- Cultural knowledges

- Health, wellbeing and identity

- Economic participation and social and cultural economic development

- Water and food security

- Remote and rural communities.

As the report notes, climate change is likely to disproportionately impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in terms of ways of life, culture, health and wellbeing as well as food and water security and livelihoods. It also notes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples “have experience, knowledge and practices that can support adaptation to climate change”.

Doing more. Doing better.

The assessment poses hard questions about how climate change will affect every system vital to Australia.

Ideally, such an assessment would be carried out every five years and be mandated by legislation.

Future assessments should comprehensively examine global impacts and their flow-ons to Australia. As the COVID-19 pandemic showed, Australia is part of a global system when it comes to human health and supply chains. Defence, trade and finance all are international by nature. And climate change refugees from the South Pacific are already arriving.

The assessment makes clear that current efforts to curb and adapt to climate change will not prevent significant harm to Australia and our way of life. We must do better – and do it quickly.

Young people, and unborn generations, can and will hold us all to account on our progress from today.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation, and was co-authored with Tas van Ommen, who consulted on the production of technical report material as part of the NCRA.