When Chris Murray was a teenager growing up in Dublin, he loved sports but lacked talent. Like thousands before him, he found salvation in martial arts classes. He became stronger, more flexible, and bullies left him alone. Later, he discovered that the classes were correcting his scoliosis, or curvature of the spine.

The lessons in Five Ancestors Fist also fed his imagination. “What adolescent in Irish suburbs wouldn’t be enriched by suggestions of a faraway world with martial arts temples and warriors who lived by codes of honour?” he writes in his book, Crippled Immortals. “And what slight schoolboy wouldn’t be enticed by the thought that bullies might be overcome by deftly applying the laws of physics?”

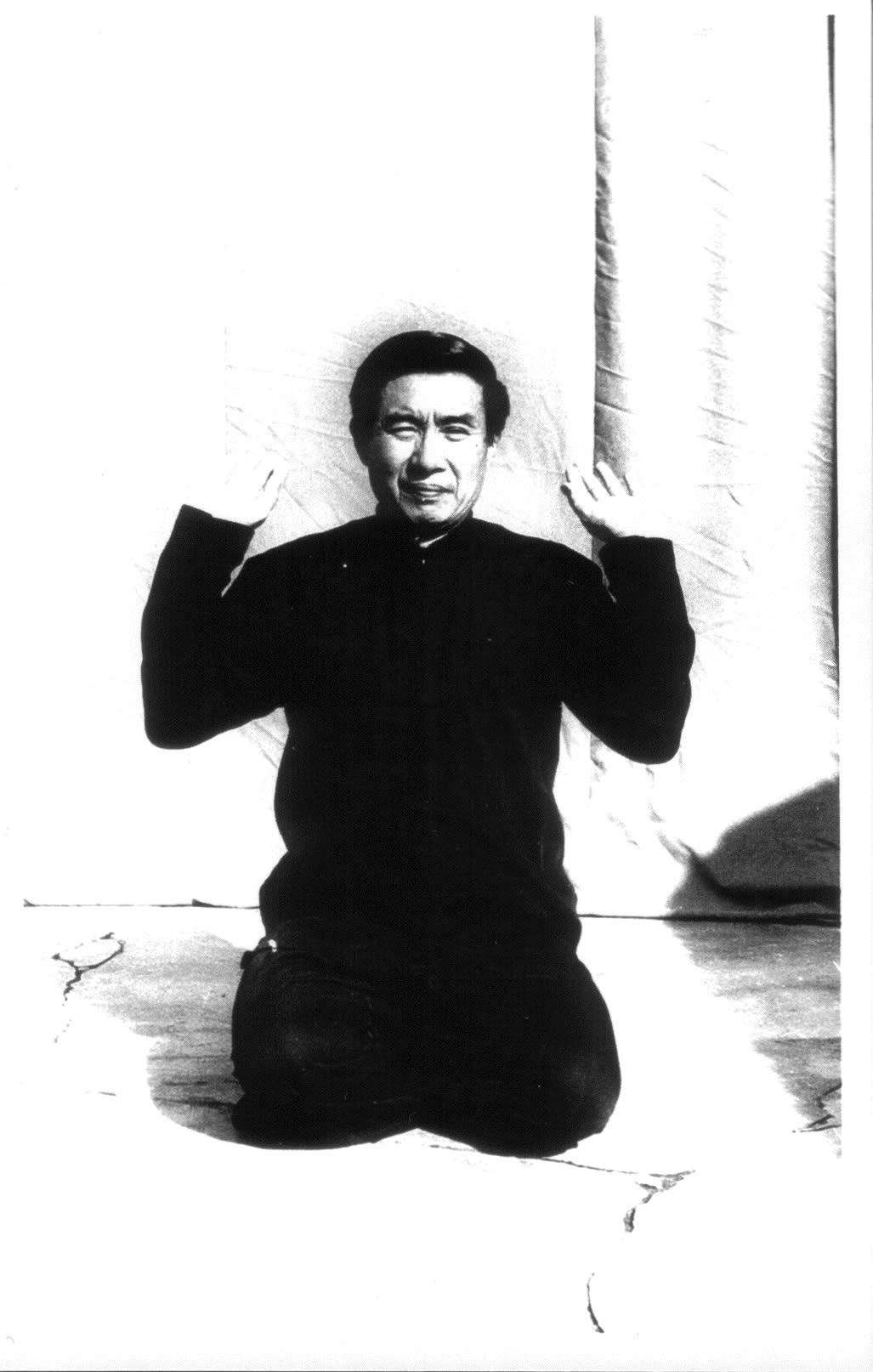

Dr Murray is now a lecturer in English literature at Monash, specialising in the Romantic poets. Crippled Immortals is also a romance of sorts, describing his two years in Singapore under the tutelage of martial arts teacher Chan See-Meng, a former banker who’s now in his 70s. Master Chan was himself a student of the revered Chinese adept Chee Kim Thong – who, as it happens, was the head of the academy that introduced the teenage Murray to martial arts, or gongfu.

Murray’s book describes practice sessions in multi-storey Singapore carparks, his deepening friendship with Master Chan, and their surprising conversations over tea and noodles in markets and food courts. But it’s also an account of the esoteric tradition that’s at the heart of martial arts practice, and the difficulty of maintaining that tradition in a sceptical and materialistic world.

An extraordinary life

The story of Chee Kim Thong’s extraordinary life is told, too. He learned gongfu as a poor boy growing up in China, and was a member of the Big Knife army – the last known army to deploy martial arts – that resisted the invading Japanese.

He became a prisoner of war before escaping to Malaysia, where he lived in a remote village, teaching gongfu and practising Chinese medicine. His gongfu gifts were so advanced that he was referred to as the “old man” while he was still in his 20s (the name reflects Chinese beliefs in reincarnation). Eventually he set up the Chee Kim Thong Pugilistic and Health Society to teach gongfu. But for most of the “old man’s” students the true art remained elusive – they lacked either the dedication, the talent or the discernment to become adepts.

Master Chan became Chee Kim Thong’s student in the early 1960s. He was initiated and devoted himself to gongfu and its codes – including modesty, obedience and a distaste for violence for its own sake. But in later years, members of the Chee Kim Thong Pugilistic and Health Society refused to recognise Master Chan’s claim to have been Chee Kim Thong’s “most precious” disciple. This created a problem for seekers wishing to learn Chee Kim Thong’s method. Where to find the true keeper of the flame?

“There has never been a reliable method to document the principles of martial arts, nor a trustworthy system of accreditation for professed teachers,” Murray writes. Western classes “in particular are often just fitness sessions with Orientalist flourishes. The dedicated student knows that the only way to ensure accuracy of transmission is to find a great master, or at least a teacher who studies under a great master. And the devoted student has to be somewhat obsessive, maybe a little crazy.” On the other hand, a master also needs students, because without them their art would be lost.

"I realise that it’s something different to what I thought it was. I came to decide that it’s primarily a self-cultivation practice that prepares the body for meditation – which is not how I would have assembled those pieces years ago when I started out.”

When Murray was still living in England, he found Master Chan on an understated website. Murray emailed him, and they had a polite exchange in which Murray related his own meeting with Chee Kim Thong when he visited his Dublin school.

Then Murray unexpectedly received a fellowship to Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University. He had recently married, and, coincidentally, had spent his honeymoon in Singapore. The Nanyang fellowship was a turning point. Murray had been trying to break through as a singer-songwriter in a rock band, and had come to accept that making a living as a musician was “almost impossible”.

Singapore offered him a chance to build an academic career, and to pursue his studies in gongfu. He arranged to meet Chan See-Meng on his arrival in 2011, and began lessons soon after. “I gained someone, like a surrogate father, in Singapore,” he says. “And I gained a kind of cultural immersion, which was extremely fortunate. Caucasians are usually not allowed into the inner circle.”

Although the classes were informal, a high standard was set. Time and again, Master Chan told Murray that his poor practice made him want to “vomit blood”.

“When he saw me performing what I had learned in Ireland and the UK, the first thing he said was that I was missing the correct concentration,” Murray says. This was the key to any advanced practice.

“Attempting to force your mind won’t work,” Murray says, “and being too lax won’t work. It’s like a steady stream. There’s a point at which I describe a warm-up exercise and I say, imagine a rush of water shooting out your fingertips. And you sustain that. And that is essentially an enormously beneficial ‘secret’ – I use the word ‘secret’ in quotation marks – of how concentration works in martial arts. If you apply that principle, your strength on contact with another person will increase vastly.”

Worthwhile benefits

While Murray was drawn to the inner path – the teaching within the teaching – he accepts that most martial arts students couldn’t be bothered with the repetitive and, on the face of it, uninteresting exercises that are involved. And that’s OK. “I think that if you enjoy [a martial art], and it’s good for your health, and you’re better at self-defence than you would be without it, those are three enormous benefits – you don’t need anything more elaborate than that. They’re all worthwhile reasons to pursue it.”

But he was drawn to the higher art; an attraction that beguiled Murray before he understood exactly what he was signing up for. “I have an affinity with this art,” he says. “I’m led along this path, and I realise that it’s something different to what I thought it was. I came to decide that it’s primarily a self-cultivation practice that prepares the body for meditation – which is not how I would have assembled those pieces years ago when I started out.”

One of the pillars of the gongfu Murray learns in Singapore is the “soft art”, which, according to Shaolin legend, was first introduced by a nun in a purple robe, who challenged the masters of the day to overcome her. When they could not, they incorporated the lessons she taught. “The female is a very important presence in high martial arts,” Murray says. The soft art “will always overcome the more brutish martial arts”.

He gives the example of his wife, Claire, who sometimes joined him in his classes with Master Chan. Although she didn’t have his dedication, he says she was more talented and quickly grasped the principles of the “soft art”, which involves not clenching the muscles when resisting an opponent.

“You have to concentrate in a particular way,” he says. “She was training with a person who I have renamed as Travis in the book. He’s a 55-year-old man who must weigh several stone more than Claire does. We were holding each other, resisting each other. He couldn’t do it to save his life. She could do it instantly – she could fling this more experienced, heavier martial artist on his back. He was enraged, as it turned out. I got it, eventually, I learnt it, but it was much more natural to Claire, because I think the brute instinct is less present.”

Murray’s lessons with Master Chan have certainly improved his gongfu skills, but the benefits go deeper. “I have a more relaxed attitude to effort now,” he says, “a kind of perspective. And there’s a peace with that.”

In his book he writes: “Some practitioners are convinced that unseen powers exist that bring us all together. But it’s the gongfu itself that draws us in to begin with. A little practice yields modest health benefits. A lot of practice brings us into strange realms of consciousness and bodily sensation. Those who attempt Chee Kim Thong’s arts are forever changed."