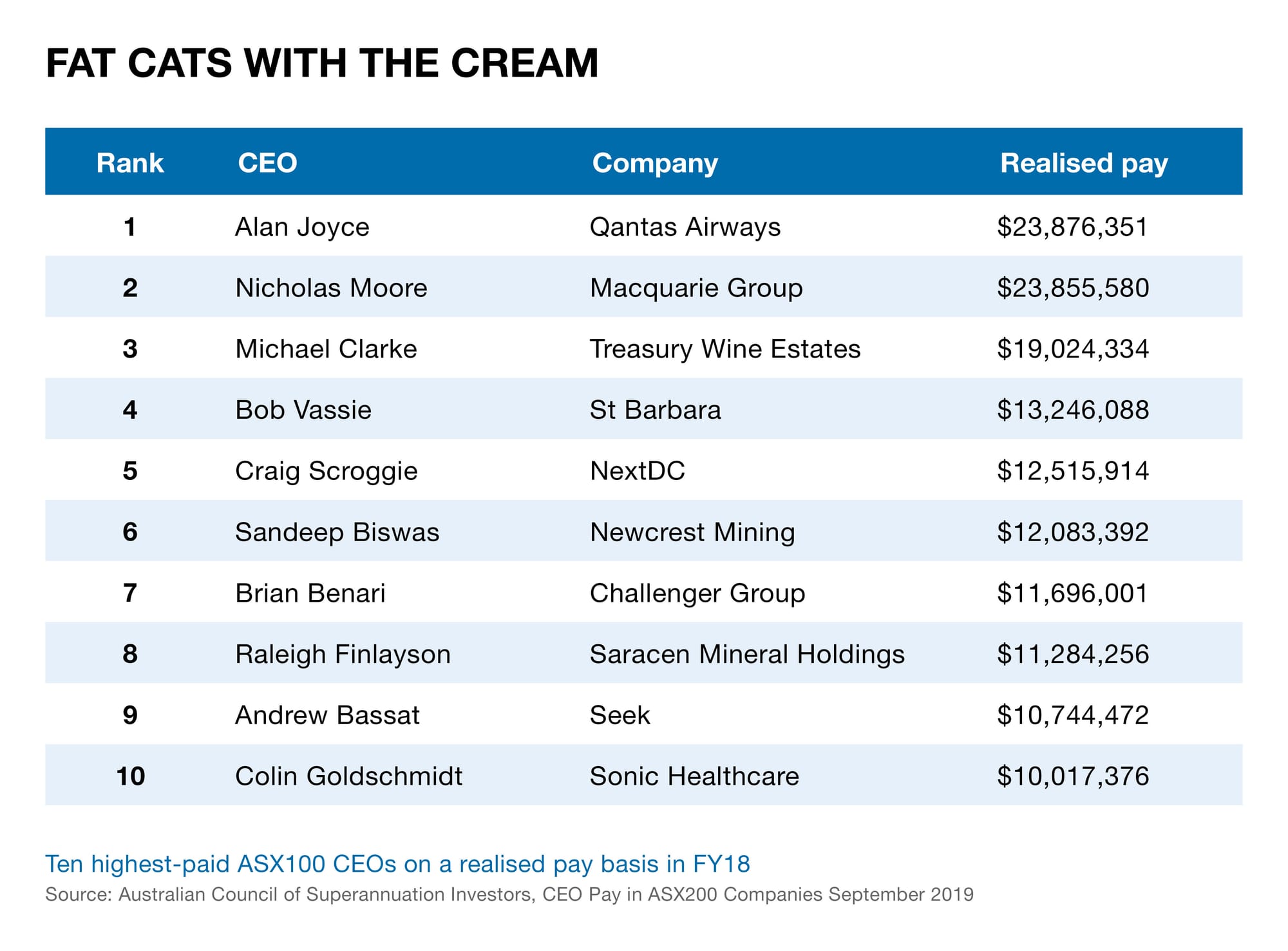

So, $23,876,351 – it’s a massive number any way you look at it, and earned Qantas CEO Alan Joyce top spot in the recently released Australian Council of Superannuation’s annual CEO ASX200 remuneration report.

Joyce’s pay packet, which works out at about $459,000 per week, is about 270 times what the average full-time Aussie makes, and draws into sharp focus the pay gap between our top CEOs and average workers.

Factor in that Australians are dealing with some of the highest household debt in the world, while still strongly distrusting corporations to "do what is right", and many feel outraged.

So, why are CEOs paid so exorbitantly compared to the rest of us?

CEO pay inequality

That inequalities exist in society is hardly news.

Over the years, the CEO pay ratio has become an intuitive indicator of excessive corporate pay and broader societal inequalities. This figure represents the ratio between CEO pay and the average or median salary of non-executive employees, with higher scores suggesting greater inequality. The numbers vary widely per country, with Australia featuring in the global top 15 in CEO pay disparity, according to some estimates. However, despite the popularity for naming and shaming corporate fat-cats, the ratios are more indicative than absolute.

CEO compensation packages are complex. So complex, in fact, that mathematical techniques developed to build the atomic bomb are sometimes used to make sense of them. Add different disclosure requirements, varying vesting periods for options, and the incomparability of jobs that require varying skill sets, experience, career investments, legal accountabilities and tenure expectations, and these ratios quickly become fairly uninformative in and of themselves.

Like all economic indicators, one must read the fine print. For instance, whereas it's indeed newsworthy to compare ASX CEOs' compensation to the general working population, some market research numbers suggest that the average CEO salaries in Australia at large are closer to A$200k per year.

When compared against these numbers, which would include the salaries of CEOs of small and medium-sized enterprises (which would account for well over 90 per cent of all Australian businesses), the "average CEO" earns somewhat over double what the "average worker" earns in Australia. Not that newsworthy.

But let us focus back on the ASX200 CEOs and accept the stats for now. After all, our outrage is based on what we believe to be true, not necessarily what is.

How much are CEOs worth?

In many ways, it's not whether CEOs are overpaid or not. Rather, whether they're proportionally paid relative to the value they add. Undoubtedly, some CEOs are overpaid; others, perhaps, underpaid.

One way to get a sense of what would be a fair compensation is to understand how much CEOs actually matter. Strategy scholars have sought to quantify the value of a CEO through a variety of sophisticated statistical techniques. The ensuing "CEO effect", the average contribution of a CEO to a company’s bottom line, ranges from as low as 4.1 per cent to as high as 42.4 per cent in some settings.

Now consider that the majority of a CEO’s pay comes from "pay for performance" provisions, not so much their fixed salary. If we then consider that Qantas made A$1.8 billion profit most recently, then even by the least conservative estimate of a CEO’s value added, the proportional pay becomes less unreasonable. Still high perhaps, but also less unreasonable.

The flipside is, of course, that if we pay CEOs according to this simplified logic, a CEO would also have to repay the company if they ran it into the ground. Few, I believe, would take that deal.

So why are some underperforming CEOs still overpaid?

Characteristics of overpaid CEOs

CEO pay is not purely market-driven or performance-driven.

A comprehensive analysis recently ratified the intuition that powerful CEOs tend to secure higher compensation. This highlights a tricky balancing act for boards: CEOs need to have sufficient power to drive strategy efficiently, yet they can exert this same power to secure higher compensation. Efforts to minimise CEO power are hotly contested, as recent failed attempts to reduce Mark Zuckerberg’s power at Facebook have shown.

Narcissistic CEOs also seem particularly adept at commanding higher pay. One would think that an easy fix would be to simply replace them with leaders who exhibit other personality profiles. However, the challenges of filling the executive suite with traits such as humility, are well documented.

In other cases, CEOs may be overpaid for simply being lucky or, as the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking and Superannuation and Financial Services further uncovered, CEOs may receive high compensations due to poor corporate governance and lapses in regulatory oversight.

These and other reasons aside, excessive CEO compensation still affects companies.

Consequences of overpaying CEOs

It's hard for the passive observer to truly judge whether a CEO is actually overpaid (or underpaid). Rather, CEO pay serves as a point of reference for ascertaining the fairness of our own situation. Given that many of us think we are better than we actually are, we may particularly experience the CEO pay gap as unfair. These feelings of unfairness may be at the core of our outrage.

Unsurprisingly, one study documented lower employee morale when CEO compensation was perceived to be unfair. When lower-level managers feel they are unfairly compensated relative to their CEO, they're more likely to leave the company. Another study recently showed that excess CEO compensation can be harmful for the company’s reputation, with another suggesting that consumers view companies with CEO pay ratios unfavourably. Most recently, a study showed that the media may call out firms as hypocritical, when they boast about doing societal good while simultaneously paying their CEOs lavishly.

Thus, even the perception that CEOs are overpaid, and the feelings of unfairness triggered by it, seem to have real repercussions.

Should we pay CEOs less?

There is nothing inherently wrong about companies making a profit.

When this pursuit is achieved through sustainable means and governed effectively, employees may benefit from greater career opportunities, consumers may enjoy improved quality of life through innovative products and services, and corporate taxes contribute billions to the nation’s coffers. Our superannuation funds that invest in these companies provide us assurance in our old age.

There's nothing inherently wrong about proportionally rewarding those who competently, ethically and empathetically lead this endeavour.

It's also important to keep in mind that the top job may not be as glamorous as some may think. In her farewell speech from PepsiCo, Indra Nooyi lamented that her success came at the cost of spending more time with her family and children. CEOs also commonly face sleep deprivation and work more than 60 hours a week, in what's considered one of the most stressful jobs on the planet.

In silence, they deal with a range of unspoken personal, mental health and physical health issues. This is obviously not a call for pity, but a reminder that the job may come at a cost that not all of us would be willing or able to bear.

At the end of the day, we're all entitled to our feelings of unfairness about CEO pay, but perhaps the question going forward should be: How much would you charge to do this job?