A rollback of free trade agreements could lead to a loss of 270,000 Australian jobs and a reduction in household incomes by about A$8500 a year, according to a report released by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

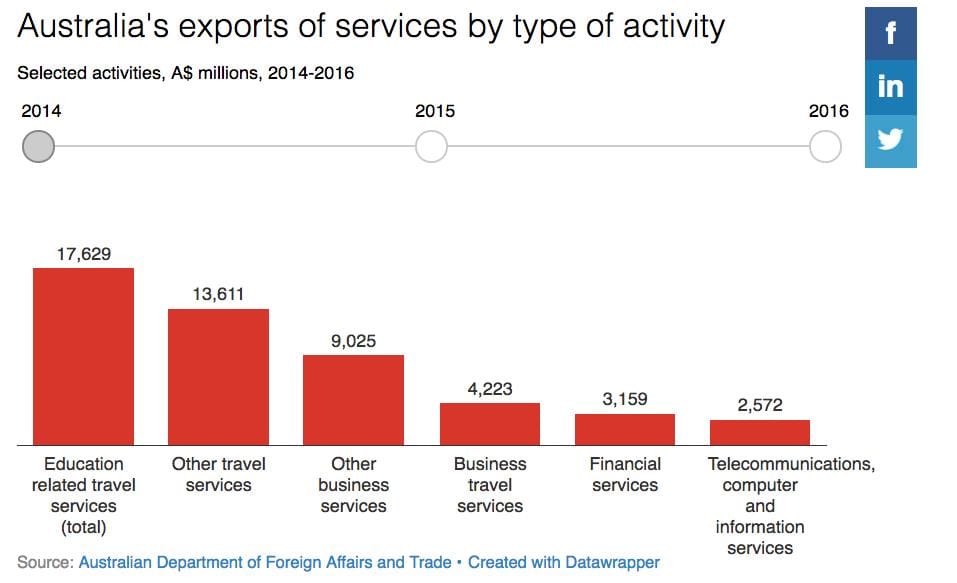

But this is an incomplete picture of the factors that affect trade, both now and into the future. Services (such as education, tourism and telecommunications) now dominate Australian production and exports. The DFAT report is based on an assessment of trade and exports over the past 30 years, during which merchandise and manufacturing were more important.

Services are not nearly as negatively affected by tariffs as manufacturing exports were. So even if there were a sudden bout of protectionism around the world, it is unlikely to have the drastic consequences that the DFAT report predicts. Furthermore, the report fails to consider broader socioeconomic outcomes from trade, such as the impact on inequality.

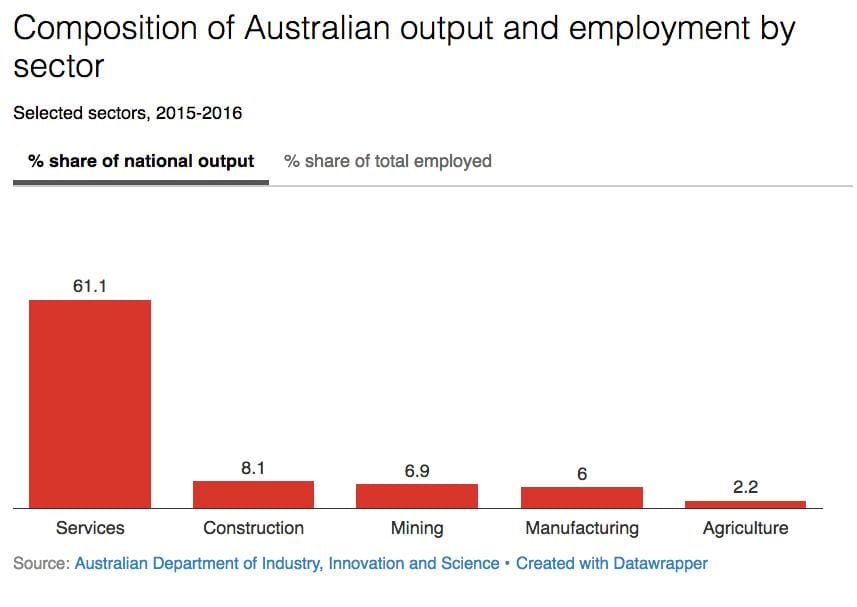

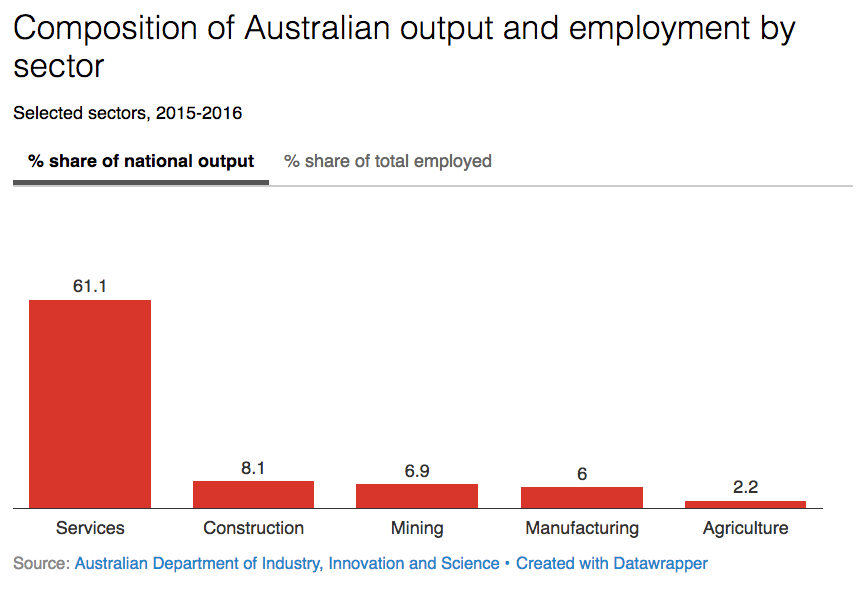

As you can see from this chart, services account for roughly 60 per cent of our national output (approximately A$1.02 trillion). The sector employs four of every five Australian workers and contributes about 40 per cent to our export earnings.

These are outcomes of Australia’s structural change in industrial production that has, over the years, moved away from the production of agriculture and manufacturing to that of services. This trend will only continue, and services are likely to be Australia’s leading export into the future.

Of course the export of services, like all forms of international trade, can be subjected to barriers. However, unlike manufactured goods, the most important barriers to services trade aren’t imposed at the border in the form of tariffs and the like.

Rather, the barriers to services occur within markets themselves in the form of domestic regulations, which range from contract enforcement, to labour market regulations and compatibility requirements for communication technology. This means that services exports are unlikely to be meaningfully affected by the rollback of free trade agreements.

In fact, if structured correctly, embracing a tide of trade protectionism could be beneficial for many Australian exporters and households. This is demonstrated by our recent research on mobile telecommunications services exports within the multilateral Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) region.

Our preliminary findings show that, in terms of profitability, Australian services firms with international operations in emerging services would benefit from countries harmonising domestic regulation. For example, by setting common standards between mobile telecommunications services among among member countries.

In the telecommunications sector alone, improving and harmonising domestic regulation under a multilateral framework such as TiSA would raise average net company profitability by 1.73 per cent.

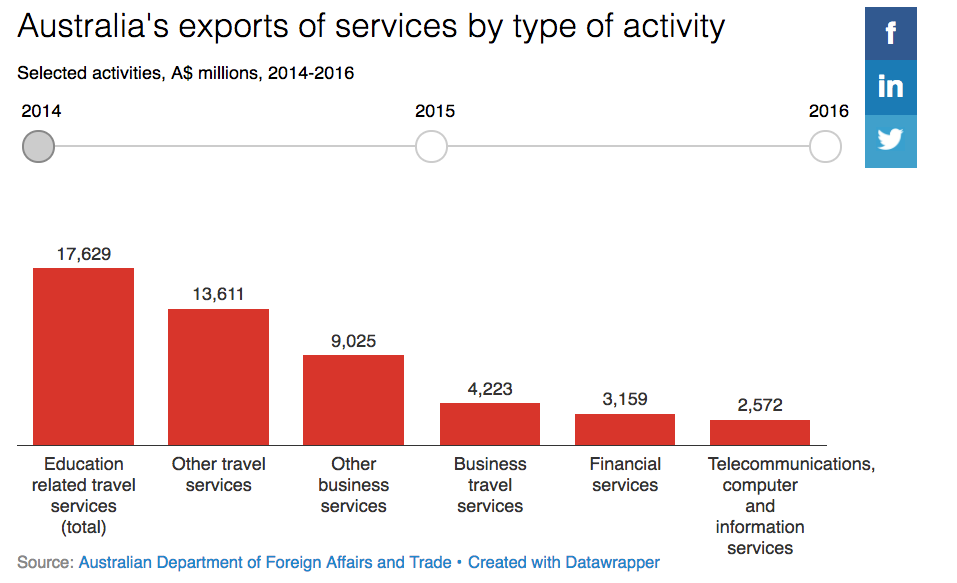

Telecommunications services are not the largest export sector for Australia. The export of education and travel services are significantly higher in volume. But a similar argument to that of mobile telecommunications can be made for harmonising standards in skills and training in key education export markets for Australia.

Other trading powers, especially those championing TiSA, like the European Union and Japan, find themselves in similar positions and are prompting a drive to establish a services focused free trade agreement.

Read more: Three charts on: G20 countries’ stealth trade protectionism

The problem with reports like the one from DFAT is that they exclude services and the need for regulatory harmonisation. The focus on merchandise tariffs also implies that the only tool available to “stop protectionism” is the further deregulation of international markets, as tariffs are already close to zero.

In fact, no major economy is currently contemplating blanket rises of tariffs, not even Trump’s administration. The United States is instead pushing for the literal application of anti-dumping and countervailing measures against distorted trade of selected countries.

To put it simply, tariffs in merchandise trade are no longer the key arena of protectionism in the 21st century. Rather, it is the combination of factors including the lack of regulation and common standards in the international markets for emerging services, as well as the resilience of non-trade barriers by emerging economies.

Ultimately, this is all aggravated by the unilateral geopolitical strategy of the US to legally enforce trade remedies against non-compliant economies of countries that challenge the American world order, such as China, Iran and North Korea.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

David Treisman is an economics lecturer in the Bachelor of International Business course at Monash Business School. He is affiliated with the Contemporary European Studies Association of Australia and the Royal Geographic Society.

Giovanni Di Lieto is a lecturer in the Bachelor of International Business course at Monash Business School. He is affiliated with the Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA).