Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

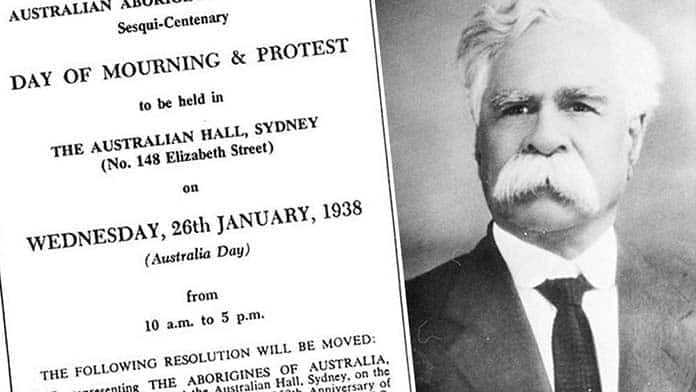

Ninety years ago, Yorta Yorta leader William Cooper dreamed of Aboriginal people being represented in the Commonwealth Parliament. In August 1933, he set about petitioning the British king, George V. The key demand was for:

“... a member of parliament, of our own blood or white men known to have studied our needs and to be in sympathy with our race, to represent us in the Federal Parliament.”

As the referendum for a First Nations Voice to Parliament draws near, it’s worth looking back on this important part of Australia’s history.

‘Thinking black’

What Cooper was asking for was a means by which Australia’s lawmakers could be informed of the views of Aboriginal people. He believed this fundamentally important to his people’s wellbeing, because he knew those who governed their lives acted without any consideration of their views.

He also knew those views differed from the ones held by white Australians. This was because, he asserted, only Aboriginal people could “think black”.

“You may read the views […] of sympathetic white men. But they are not our views,” Cooper told a white journalist in September 1937. “We are the sufferers; the white men are the aggressors.”

Blackfellas, Cooper was saying, had different views to whitefellas because of their historical experience of dispossession, death, decimation, displacement, deprivation and discrimination.

This was a matter of what Cooper once called “racial memory”. It was something “in the blood […] which recalls the terrible things done to them in years gone by”.

A ‘moral duty’

Petitions tend to be couched in deferential terms – Cooper characterised the plea in his petition as “humble”, sought to “respectfully sheweth” the matters it presented, and “humbly pray[ed]” the king would intervene.

But they usually suggest a government has an obligation to respond – Cooper argued the British Crown had a “moral duty” to do so because he believed it had issued a commission in 1788 stating “the [country’s] original inhabitants and their heirs and successors should be adequately cared for”.

Petitioners also tend to assume there’s a higher form of authority than a local one to whom they can appeal. British responsibility for Australian affairs had ceased with the founding of the Australian nation in 1901.

Despite this, Cooper believed the British monarch continued to have a special right to intervene in those affairs, and that Aboriginal people had a right of appeal to him or her on the grounds they had reserved certain powers in this respect.

Getting signatures for what Cooper called “this great work” was very difficult, not least because he had limited means.

Several frustrating months passed before government authorities reluctantly agreed to grant him permission to circulate his petition among Aboriginal people who lived under so-called Protection Acts. But Cooper was tenacious. He believed it was the duty of every Aboriginal man and woman in the country to sign, and hoped to get the signatures of all of them or at least those living on missions and reserves.

Dismissed but not deterred

By 1935, the petition was ready to be submitted. But Cooper decided to hold it back in the hope a major meeting of all the administrators of Aboriginal affairs would see the federal government adopt its recommendation of a new policy to “uplift” his people. Yet this came to nothing.

“We did look to this [meeting] as marking an epoch in our history,” Cooper told a federal minister.

“We have got nothing definite except the refusal of our claim for representation in the federal parliament,” he exclaimed; “no result but … 80,000 Aborigines [sic] in Australia […] refused one representative in Parliament. Yet in New Zealand the same number of natives have four members and one minister for native affairs.”

Soon after, Cooper sent the petition to prime minister Joseph Lyons and asked him to forward it to the king. Lyon sought the advice of the relevant government department.

The permanent head of the department of the interior was dismissive of Cooper’s plea for parliamentary representation. Lyon was more sympathetic, something a well-informed political observer attributed to the fact he remembered the wholesale slaughter of Aboriginal people in his own state, Tasmania.

Lyon called for legal advice and directed his office to tell Cooper he had “the fullest sympathy” with Cooper’s wish that the interests of the Aboriginal people be “adequately safeguarded”.

In the end, Lyons’ cabinet accepted a recommendation from the department of the interior that no action be taken. This was on the grounds its own minister could represent Aboriginal people, and there was nothing to be gained from forwarding the petition to King George VI (who, by then, had succeeded King George V). With that, it seems the petition roll was consigned to a dustbin.

Yet Cooper never gave up hope. In 1939 and 1940, he repeatedly asked prime minister Robert Menzies to grant his plea.

He died shortly afterwards, but his dream of parliamentary representation for his people did not, living on in the hearts and minds of another generation of Aboriginal campaigners.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.