Where there’s innovation in technology, there will often follow manipulation.

Photoshopping, for example, followed photographs, creating fiction from photographic fact, distorting our visual sensory inputs. It was, in some ways, the precursor to an uncertain future of truth in digital visual media and, more nefariously, image-based abuse (IBA) and revenge porn.

Sometimes the airbrushing was crude and noticeable, but in the hands of an expert with advanced technology, you’d struggle to know that the front-page magazine model was imperfect; that the original photograph showed flaws.

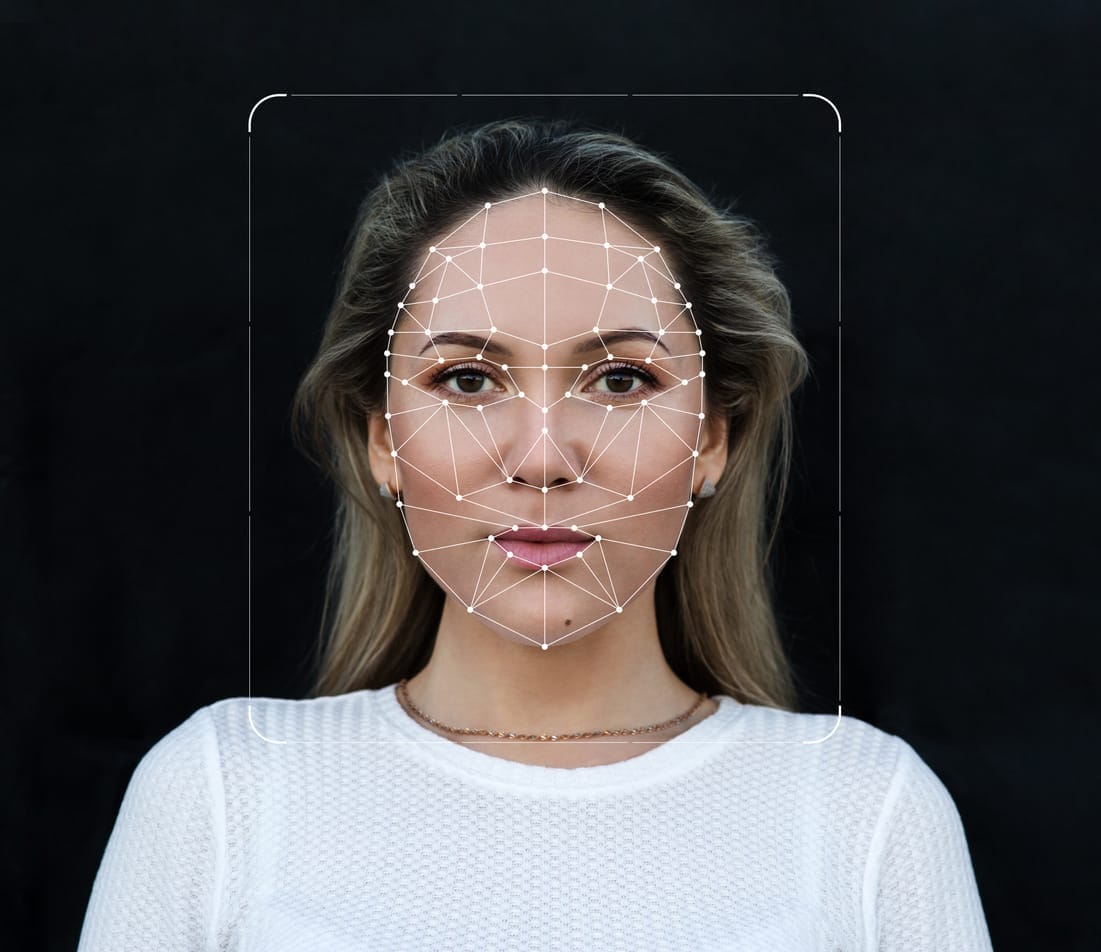

Then came video, and it was only a matter of time before the same kind of manipulation emerged. Now, face-stitching technology and artificial intelligence (AI) is further blurring the lines between truths and lies.

Everything is not as it seems, looks or moves

In 2018, a new app was developed giving users the ability to swap out faces in a video with a different face obtained from another photo or video – similar to, but less crude than, Snapchat’s “face swap” feature.

It’s essentially an everyday version of the kind of high-tech computer-generated imagery we see in the movies, such as the cameo of a young Princess Leia in the 2016 blockbuster Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, which used the body of another actor, and footage from the first Star Wars film created 39 years earlier.

What this means is that anyone with a high-powered computer, a graphics processing unit and time on their hands can create realistic fake videos – referred to as “deepfakes” – using AI.

The problem is that the popularity of the technology has exploded and become easy to use to create non-consensual pornography of partners, friends, work colleagues, classmates, ex-partners, celebrities and complete strangers – which can then then be posted online.

Known as “morph porn”, or “parasite porn”, fake sex videos or photographs aren’t a new phenomenon, but what makes deepfakes a new and concerning problem is that AI-generated pornography looks significantly more real and convincing than what has come before it.

In December 2017, Vice Media’s Motherboard online publication broke the story of a Reddit user known as “deepfakes”, who used AI to swap the faces of actors in pornographic videos with the faces of well-known celebrities.

Another Reddit user then created the desktop application FakeApp in 2018, which allowed anyone – even those without technical skills – to create their own fake videos using an open-source machine learning framework.

The technology uses an AI method known as “deep learning”, which involves feeding images into a computer that then assesses which facial images of a person will be most convincing as a face swap in a pornographic video.

Another form of image-based abuse?

Creating, distributing or threatening to distribute fake pornography without the consent of the person whose face appears in the video is a form of image-based abuse (IBA). Also known as revenge porn, it is an invasion of privacy and a violation of the right to dignity, sexual autonomy and freedom of expression.

In one case of morph porn, an Australian woman’s photos were stolen from her social media accounts, superimposed onto pornographic images and then posted on multiple websites.

She described the experience as causing her to feel “physically sick, disgusted, angry, degraded, dehumanised”.

In another case, a man acquired the services of a technical expert to create a deepfake pornographic video of his ex-partner using about 400 images he had downloaded from her Facebook page.

US actress Scarlett Johansson has spoken about how images of her face have been used to create fake porn, and earlier this year, US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was the victim of a manipulated pornographic image being “leaked” to the media.

How prevalent is IBA?

Our survey of 4274 Australians aged 16 to 49 years found that one in five (or 23 per cent) had experienced some form of IBA. Most common were sexual or nude images being taken of them without their consent, with one in five reporting these experiences. Also common was sexual or nude images being sent on to others or distributed without consent, with one in 10 surveyed reporting these experiences.

We also asked participants about perpetration, with one in 10 disclosing that they’d engaged in at least one IBA behaviour. Almost nine per cent said they’d taken a nude or sexual image of another person without that person’s permission. Almost seven per cent said that they’d distributed an image without permission, and one in 20 said they’d threatened someone with distributing their image.

The actual rate of IBA is likely to be much higher. These figures only represent instances where victims have become aware that someone was taking or distributing (or threatening to distribute) their images without their consent, or where perpetrators have admitted to doing so.

Despite a diversity of distribution sites and sharing practices, the consistent link between all of the sites viewed was the sharing, viewing and discussing of images, predominantly of women, by and for heterosexual men.

There’s no doubt that some victims won’t know that someone is taking or sharing images of them – for example, via mobile phone, email or internet sites. And, of course, some perpetrators won’t admit to having engaged in this form of abuse.

While it is not possible to put a figure on the number of online sites that trade in IBA material, we completed a study exploring the nature and scope of IBA material appearing on different high-volume online sites for the Australian Office of the eSafety Commissioner to help inform the development of a world-first national online IBA portal.

During a three-month period in 2017, we identified 77 publicly accessible (non-member and free) sites that hosted, or appeared to host, non-consensual nude or sexual imagery.

Despite a diversity of distribution sites and sharing practices, the consistent link between all of the sites viewed was the sharing, viewing and discussing of images, predominantly of women, by and for heterosexual men.

We did not come across any dedicated website, image board, community forum or social media page that specialised exclusively in the upload, distribution and discussion of semi-nude, nude or sexual images of heterosexual men (although there were some sites that included sharing non-consensual images of gay men). In addition, we found the breadth, membership and interest in these sites indicated there was a large and growing demand for IBA.

Solving AI-generated image-based abuse

While AI can be used to make deepfakes, it can also be used to detect them. It’s just a matter of keeping up with the explosion in popularity and the technological advances to expose the flaws in the increasingly complex algorithms.

One area researchers have focused on is blinking. Because people tend not to post photographs of subjects with their eyes shut, the deep fake algorithms are less likely to create faces that blink naturally.

But what’s still needed is more research teams from the humanities, social sciences and STEM coming together to develop ways to prevent AI-generated IBA.

To adequately address the issue, it’s going to take a combination of laws, cooperation from online platforms, as well as technical solutions. Like other forms of IBA, support services, as well as prevention and awareness, are also important.

Find out more about this topic and study opportunities at the Graduate Study Expo